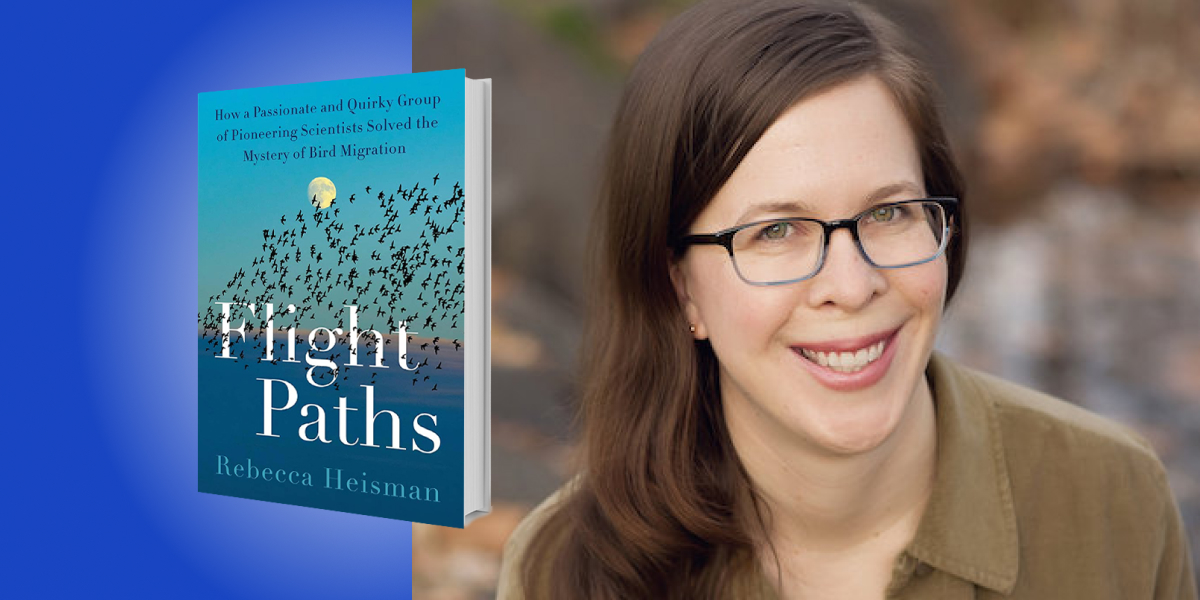

Rebecca Heisman is a one-time aspiring ornithologist turned science writer. She has been writing about birds and the people who study them for almost a decade now, with her work being featured in publications such as Audubon Magazine, Sierra Magazine, Hakai Magazine, and Living Bird.

Below, Rebecca shares 5 key insights from her new book, Flight Paths: How a Passionate and Quirky Group of Pioneering Scientists Solved the Mystery of Bird Migration. Listen to the audio version—read by Rebecca herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Don’t just ask what we know—ask how we know it.

The facts about bird migration are amazing. You may have heard about birds that navigate using the Earth’s magnetic field or birds that make nonstop flights across the Pacific Ocean. But behind every gee-whiz science fact is a story about the hard work and creativity that went into uncovering it.

For example, to prove that birds migrated over the open water of the Gulf of Mexico to get between North and South America, a Louisiana ornithologist working in the 1940s boarded a boat for the Yucatan with a telescope, training it on the full moon at night to count the silhouettes of birds passing across its bright face.

A decade later, a pair of young scientists in Illinois rigged up a tape recorder with a bicycle axle to hold the 6,000 feet of tape they’d need to record a full night of the calls of birds passing overhead.

Today, many of the miniature tracking devices used to record birds’ movements require researchers to recapture the birds to get their gadgets back and download the data—and putting a tracker on a bird, waiting while it flies to another continent and back, and then catching that same individual bird a second time is not an easy task.

How we know about bird migration—the many creative ways that bird-obsessed scientists have unraveled the mysteries of where birds go and why—is often as fascinating as what we know.

2. Look for inspiration in unexpected places.

When I started researching, I didn’t realize that I would have to understand the basics of everything from machine learning to isotope chemistry. But it turns out that ornithologists have borrowed techniques from nearly every scientific field to study bird migration.

It didn’t take long after the development of radar in World War II for ornithologists to realize that flocks of birds showed up on the device just as well as fighter planes and rainstorms.

“Fields of study other than our own can offer refreshing shifts in perspective, leading to breakthroughs that would never happen if we all stayed in our own lanes.”

The invention of the transistor in 1947 and the launch of Sputnik a decade later inspired a generation of wildlife scientists to build radios for tracking individual birds in real-time.

And when the Human Genome Project led to breakthroughs in high-volume genetic sequencing, soon ornithologists were applying those techniques to bird DNA, mapping genetic variation in populations so they could tell where in North America a migrating bird originated from—just a feather or a drop of blood.

In researching this book, I talked to electrical engineers, computer scientists, physicists, geochemists, and at one point even a philosopher. It’s a reminder that fields of study other than our own can offer refreshing shifts in perspective, leading to breakthroughs that would never happen if we all stayed in our own lanes.

3. Follow your passion.

Occasionally while researching, I was intimidated to email a famous scientist I’d never met and ask if they’d talk to me about their work. Often, I wasn’t even asking to interview them about the work they were famous for, but instead about a scientific technique they’d invented before moving on to other work, or a quirky side project. But every single one said yes to talking to me, because they all truly love what they do and want to share it with others.

Again and again, I got to see people light up as they described their life’s work. People who are doing work they truly care about are generous and motivated, and their excitement comes through in every conversation.

I also asked each bird scientist how they got interested in ornithology, and it was clear that many of them never expected their careers to go in the direction that they ultimately did. I got so many answers along the lines of “I was a bored pre-med student, took an ornithology class on a whim, and it changed my life.”

“People who are doing work they truly care about are generous and motivated.”

Seeing the passion and enthusiasm of these scientists showed me that following your curiosity, the things that set you on fire to experiment and iterate and learn more, is never a bad idea, even if it’s not initially clear where it will take you.

4. Keep digging.

You might think that, after more than a century of studying bird migration, we’d have it all figured out. That the time for amassing more data is over, and we should be shifting our resources to conserving threatened species. But every answer opens new questions.

Bird migration research can be described as a fractal—meaning the closer you look, the more there is to see. And for wildlife conservation to be effective, we need the most detailed information possible about animals’ lives and the perils they face, so that we can identify and mitigate the specific threats that are putting species’ survival at risk.

One relatively recent concept in the study of bird migration is migratory connectivity. In simple terms, this describes the geographic links between different parts of an individual’s or a population’s annual cycle. The idea is that to target conservation efforts appropriately we need to have a full understanding of all the parts of the annual rhythm of a bird’s life. Its ecology on its breeding grounds and on its wintering grounds and along the route it takes during migration. For many species, we’re still nowhere near this level of detail.

All the habitat protection and restoration that we can possibly do in a bird species’ breeding habitat won’t do a thing to turn around population declines if the true problem is, say, unrestricted logging on their wintering grounds far away on another continent.

Migration research shows that it’s important not to just go with the first plausible solution, but to keep questioning and digging until we’re sure we know what’s really going on.

5. Find hope in action.

Migratory birds are in trouble. A landmark study published in 2019 estimated that there are three billion fewer birds in North America than there were in 1970, a nearly 30 percent decline. But, many bird experts are still hopeful about the future.

“My number one despair-fighting tip is to just go outside and spend a little time with the birds themselves.”

Many of the experts I contacted spoke about being inspired by the excitement and determination of the young students they work with, and by remembering how we’ve come together to tackle past environmental challenges, such as acid rain and the hole in the ozone layer.

The best way I’ve found to fight despair is to take action, and there are simple things anyone can do to help improve the odds for migratory birds. You can get involved by gathering data on the birds in your neighborhood—keeping a simple count of how many birds and what species you see on a walk, for example. Submit your counts to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology through their eBird app and you’ll be adding to a database used by scientists to assess the movements and long-term population trends of species all over the globe.

You can also help birds by reducing pesticide and plastic use, planting native plants in your yard to create habitat, keeping your cat indoors, and advocating for environmental policies with your legislators, to list just a few options.

And of course, if all else fails, my number one despair-fighting tip is to just go outside and spend a little time with the birds themselves.

To listen to the audio version read by author Rebecca Heisman, download the Next Big Idea App today: