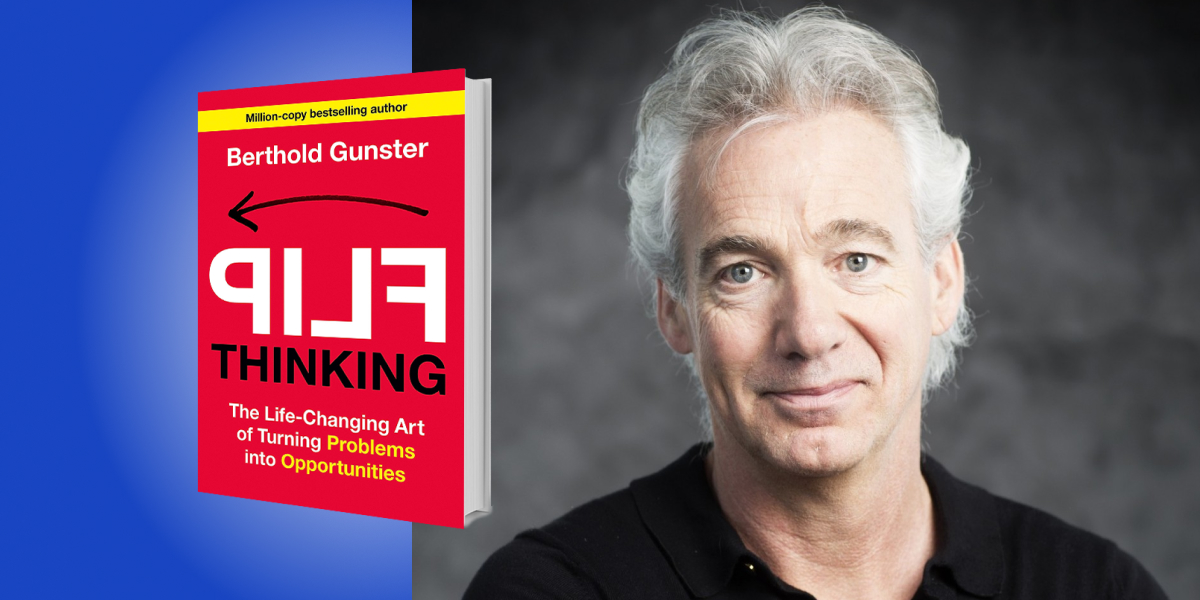

Berthold Gunster is the founder of the concept of flip thinking, otherwise known as omdenken in Gunster’s native Dutch. He has been lecturing, training, and writing about this concept for nearly 30 years.

Below, Berthold shares five key insights from his new book, Flip Thinking: The Life-Changing Art of Turning Problems into Opportunities. Listen to the audio version—read by Berthold himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Don’t say yes-but, rather, say yes-and to life.

When we are faced with problems, we instinctively want to get rid of them. We don’t like the uncomfortable feelings that go along with problems, like discomfort, pain, and grief. So, we tend to say yes-but to problems. We want to solve, avoid, or prevent them.

Fortunately, this strategy often works. You can fix a bicycle tire, go to the hospital for a broken leg, or take your car to the garage when the sparkplugs need to be replaced. But some problems can’t be solved. Life does not always bend to our will. We can’t solve an incurable disease, the loss of a beloved, or the course of a hurricane. Many problems just are what they are, yet we still feel this strong urge to say yes-but to reality itself. We want to fight reality to get rid of our problems and as we deal with uninfluenceable problems, these problems remain and our frustration only grows.

The first thing you have to do to learn how to flip think is go from yes-but to yes. Accept reality as it is. When it rains, it rains. Just say yes to reality. By saying yes to unalterable problems, you convert problems into facts. This is the first step of flip thinking.

This first step you might also consider as Zen Buddhistic or stoic. Accept reality as it is. Flip thinking is not like optimism or positive thinking. The cornerstone of flip thinking is acceptance of the things we can’t change. As soon as you make this mental shift, you are immediately in harmony with the world around you.

“By saying yes to unalterable problems, you convert problems into facts.”

If flip thinking stopped at saying yes, it would be equal to resignation or surrender. After this first step comes a second: say yes-and. Accept reality as it is and do something with it. Try creating a new possibility. It’s not the cards you’re dealt, but how you play the hand.

So, go from problem to facts, and then from facts to opportunity. You could also say: go from how life should be to how life is, and then from how life is to what life could be. The world of what-should-be differs like day and night from the world of what-could-be.

Flip thinking is what children tend to do. What do grown-ups do when it rains? They avoid it. Stay indoors, carry an umbrella. What do children do? They dance in the rain.

2. The default of our brain is to solve, not to flip think.

Though flip thinking and problem-solving may sound related, they are not. In a way, they are opposites. This is a crucial distinction because we tend to fall for what I call the solution reflex.

What is our first reaction when faced with problems? Get rid of them. Solve them. Although this solution reflex is understandable, it is often a missed opportunity—even when you can solve the problem.

For instance, when a man gets older and loses his hair, he might consider this as a problem that should be solved. By wearing a toupee or undergoing a hair transplant he could very well fix this problem. When done right, everything is back to as-it-should-be.

But how could one flip think hair loss? By embracing being completely bald as your new appearance, as your new hip look. Look at Andre Agassi, or the fictional character Walter White in Breaking Bad performed by an awesome bald Bryan Cranston, or think of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson. All of them are bald as a billiard ball, but it doesn’t make them less attractive. Being bald is not their setback, it is their desired image. They created a new opportunity out of an existing problem. They didn’t solve hair loss, they flipped it.

Solving is good, flip thinking is often better. The default of our brain is to solve, and we tend to forget that we can choose to bend along with problems.

3. Trying to solve unchangeable problems makes problems worse.

This is what I call stuck thinking. It is the exact opposite of flip thinking. With flip thinking, one goes from problem to possibility. With stuck thinking, one goes from problem to disaster. Imagine your car is stuck in the mud. You try to drive it out, but the more you spin the wheels, the deeper your car sinks.

Stuck-thinking examples come in all shapes and sizes. Social geographers know it as the waterbed effect: when you improve living conditions in a certain neighborhood without improving the adjacent areas, the problems will probably shift to those surrounding areas, rather like what happens when you push down on a waterbed. People who diet know stuck thinking as the yo-yo effect. Economists call it the downward spiral.

“With stuck thinking, one goes from problem to disaster.”

For instance, you can strictly forbid your child to smoke, but doing so can make smoking more attractive to them. Your solution increases the problem.

When solutions don’t work or make the problem worse, stop solving. Insanity is doing the same things over and over again and expecting a different outcome.

4. A problem exists of two things.

We experience problems as one single thing. When it rains, the rain seems to be the problem. When we have a flat tire, the flat tire is obviously the problem. When we lose hair, losing hair seems to be the problem. So, we tend to experience problems as one variable. Facts as they are.

But when we take a closer look, every problem always has two components. Namely reality as-it-is and our diametrically opposed expectations.

To illustrate this: when you go camping with your spouse and two children and it is raining for days, then rain is a real problem for you and your family. But when you’re a farmer in exactly the same area and it has been bone dry for weeks and finally it rains for a few days, the rain is a blessing. Every problem is always a contradiction between facts and expectations. Between what-is and what-should-be.

When you experience a problem, you can try to change reality, but you can also reframe your expectations. We tend to blame reality for problems. We feel that problems “happen” to us, as if we were unblemished and innocent and the world is constantly dumping problems in our lap. But it’s our expectations that cause us to experience a fact as a problem. We often can’t change facts, but we can always change our expectations. Realizing this doubles our influence on problems.

5. What if the problem becomes the intention?

What if the problem would be there with an aim, or a purpose? For our logical brain this question sounds absurd. Problems are by definition things we do not want. How can a problem be something we desire, or something that serves our goals? But by asking ourselves this counterintuitive question, we challenge our brain to find new ways of thinking and seek hidden opportunities.

For example, if your relationship is in a deep crisis, this is a painful problem. But what if instead of trying to neglect or solve your problems, the two of you learn from the situation? Your problems might be a stepping stone to refresh, renew, or transform your relationship. If you succeed, your relationship might become better than it ever was. Not despite your problems, but thanks to your problems.

“Problems are nothing more and nothing less than frustration that hasn’t found its shape yet.”

From now on, whenever you are confronted with a problem—small or big, personal or social, family or business—take a deep breath and ask yourself: What if this problem is the intention? What could I learn from it? What could it bring me? What could be the hidden opportunity?

Problems are nothing more and nothing less than frustration that hasn’t found its shape yet. A problem is equal to a desire, a wish, an expectation that is trying to create a new reality. When you want to flip think, embrace reality as it is, see problems as opportunities, and don’t focus on what should-be, but on what-could-be.

My home country is the Netherlands, a country that experiences water—the sea, rivers, and canals—not as an enemy, but as an ally. More than 26 percent of our country lies below sea level. The lowest area in our country lies 6.76 meters (22 feet) below sea level. Fighting the sea would be a losing game. The Dutch were forced to cooperate and live with the water. I have the assumption that with omdenken, or flip thinking, I am standing on the shoulders of our Dutch pragmatic culture. If you can’t fight it, embrace it and work with it.

To listen to the audio version read by author Berthold Gunster, download the Next Big Idea App today: