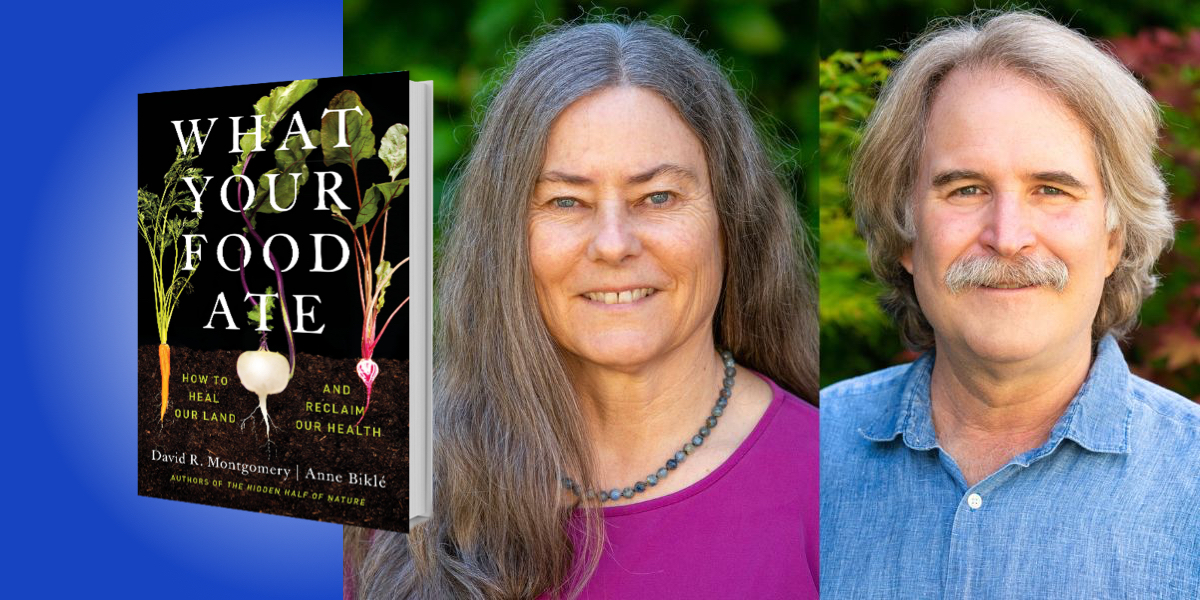

Anne Biklé is a biologist, writer, and gardener. Her husband and co-author, David Montgomery, is a geologist, MacArthur Fellow, and professor at the University of Washington.

Below, Anne shares 5 key insights from their new book, What Your Food Ate: How to Heal Our Land and Reclaim Our Health. Listen to the audio version—read by Anne herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Soil can be sick or healthy—just like a person.

Your doctor might ask about your diet, but they are not likely to ask if the food you ate came from healthy soil—but perhaps they should. Soil health profoundly influences the amount and type of nutrients that make it into crops, livestock, and, thus, onto your dinner table.

We have the power to change soil health, and indeed we have, beginning with the first pass of a plow at the dawn of agriculture about 10,000 years ago. But those changes were not for the better. If you were to take the pulse of soils beneath farms, pastures, and ranches today, you’d find a disturbing trend. Of the world’s cropland soils alone, about a third are seriously degraded. The UN estimates that this figure will increase by another third this century, making it all the more challenging for humanity to feed itself.

There are three broad groups of nutrients that soil health influences. First, are the micronutrients. These are vitamins and a handful of minerals, among them zinc and iron. Though we need just a bit of them, that small bit does big work in our bodies. Second are phytochemicals. These plant-made compounds number in the tens of thousands and function like a whole hardware store, not just the single proverbial tool. The third is the most maligned and misunderstood—the fats found in animal foods. We need a sufficient amount of two fats in particular: omega-6s and omega-3s. They help fire up and ramp down our immune system. Soil health via the interactions between plants and microbiota, and the way we raise farm animals, profoundly influences the levels of these types of nutrients in the foods we eat.

The healthiest soils have an abundance and diversity of organic matter and soil life. In fact, the former feeds the latter. A key source of organic matter is dead things—from trillions of tiny microbial carcasses to decomposing plants and animals. Among the strange things about the subterranean world of soil is that more death translates into more life, thus healthier soil, and crops and livestock with more worker nutrients.

Healthy soil is good for us biologically. This is a little-appreciated reality.

“Healthy soil is good for us biologically.”

2. Resetting the underground dinner table changes our own dinner table.

Millions of years before farmers and gardeners, before tractors and trowels, the first land plants struck up relationships with hungry soil microbes. These relationships remain as deeply beneficial to the botanical (and thus agricultural) world as those developed with pollinators.

It’s an ingenious arrangement. Plants make exudates—a vast array of carbohydrates, proteins, fats, and other compounds—that flow directly out of their roots to the microbial communities with whom they associate. But even here, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. The exudates only flow if fungal partners fetch mineral elements (like zinc and phosphorous) and deliver them to the plant’s doorstep. Certain soil bacteria metabolize exudates into new compounds and plants take them back up through their roots. These kinds of exchanges are at the heart of how plants thrive despite being stuck in one place for life.

Modern farming practices have altered these time-tested relationships which had been honed on the anvil of evolution. Plowing breaks fungal networks apart, significantly curtailing fungal deliveries of minerals. Herbicides and fungicides wreak havoc on the make-up of microbial communities by killing off most, if not all, residents. And nitrogen fertilizers turn plants into pampered slackers that don’t invest energy into making exudates.

When conventional farming undermines the partnerships between plants and soil life, crops lose out on the microbial products they previously reaped—meaning we do too. Fortunately, we can bring soil back to life through regenerative farming practices.

3. There is a hidden half of nutrition.

We collected soil and crop samples from 10 sets of paired farms across the country. Each set consisted of a conventional farm and a neighboring regenerative farm that was growing the same crop. We found that the soil on regenerative farms consistently had more organic matter and more microbial life. This resulted in much higher soil health scores than at conventional farms. Across the board, phytochemical levels were consistently higher in the regenerative crop samples. Micronutrient levels of the regenerative crops were highly variable, but on average higher than those of the conventionally grown crops.

“Phytochemicals help curb the wear and tear on cells and tissues that can initiate chronic diseases with age.”

These differences stemmed from the regenerative farmers doing three simple things. They minimized or eliminated plowing. They also kept their soil covered with plants year-round, rotating cover crops and cash crops. Lastly, they grew a diversity of crops. Some incorporated animals into their farm operations and many were using few to no agrochemicals.

Our finding of higher phytochemicals in the regenerative crops is particularly important. Plants make thousands of different phytochemicals for good reason. They use them like an onboard pharmacy, arsenal, and communication system between themselves and their microbial partners. This translates into crops far more capable of defending themselves against pests and pathogens, which in turn creates less demand for pesticides.

In our bodies, phytochemicals (like sulforaphane in broccoli and kale, and beta-carotene in carrots and squash) deliver health benefits. Phytochemicals help curb the wear and tear on cells and tissues that can initiate chronic diseases with age. They interact with our microbiome, which transforms them either into compounds with clean-up and repair power, or gives them the ability to activate genes that kill cancer cells and pathogens. This is how phytochemicals serve up preventive medicine. While calories are the fuel that runs our bodies, phytochemicals are the oil that keeps us running smoothly.

4. When it comes to the effects of eating animals on our health and the environment, we are asking the wrong questions.

We’ve all heard the advice to choose a plant-based diet because it’s better for the environment and our health. Yet not much is said in these debates regarding how the crops and much-maligned animals were raised. A plant-based diet based on conventionally grown, soil-destroying practices is neither environmentally friendly nor particularly healthful. Of course, conventional methods of raising animals—horrific living conditions and diets ill-matched to animal biology—are not eco-friendly or healthy either. If it’s bad for the land or the animal, it’s safe to say it’s not good for us either.

“If it’s bad for the land or the animal, it’s safe to say it’s not good for us either.”

Let’s examine this—take cows. What’s good for the land and good for them too? They do best on a diet and lifestyle anchored to the fat of the land: the leafy, living parts of plants, rich in omega-3 fats. In contrast, the corn or soybeans which dominate feedlot diets for bovines are rich in omega-6 fats. Since the fats that cows eat transfer to their dairy and meat, these animal foods are a big conduit for the kinds of fats that become part of our bodies. A balance of omega-6 and omega-3 fats underpins their health and ours. Omega-6 fats play critical roles in initiating inflammation, whereas omega-3 fats dial down inflammation.

Ideal for our biology is a diet that is roughly equal amounts, or up to two times the amount of omega-6 fats as omega-3 fats. Most of us eat 10 times or more omega-6 fats as compared to omega-3 fats. This has happened because we decided what animals should eat, rather than enabling the diet best suited to their particular biology—and as it happens, ours too.

Regenerative livestock grazing can rebuild soil organic matter while leaving behind a lower carbon footprint than in the feedlots where mountains of manure become methane-producing toxic waste, rather than organic matter on which soil life thrives. When it comes to animal agriculture, what’s good for them is good for us—and the land.

5. The roots of health—for better and worse—grow on farms.

Somehow, in trying to feed the world we have lost sight of nourishing people. Of course, we all need enough calories to develop from two cells into trillions, but there’s far more to our health than growth.

In chasing higher crop yields, our efforts to feed the world have conflated quantity and quality. As a consequence, conventional farming delivers fewer micronutrients and phytochemicals in our crops and an unhealthy mix of fats in our meat and dairy products. Looking forward, we need to aim beyond feeding the world to focus on nourishing it. Regenerative farming practices offer a promising route to healthy soils—the precursor for nutrient-dense crops and animals.

In the 1950s, Americans spent twice as much per capita on food as on health care. Today we spend twice as much on health care as on food. Seven out of 10 of us suffer from at least one chronic disease, many of which are diet-related maladies rooted in inflammation—everything from cancers to heart disease. Something is not working.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Anne Biklé, download the Next Big Idea App today: