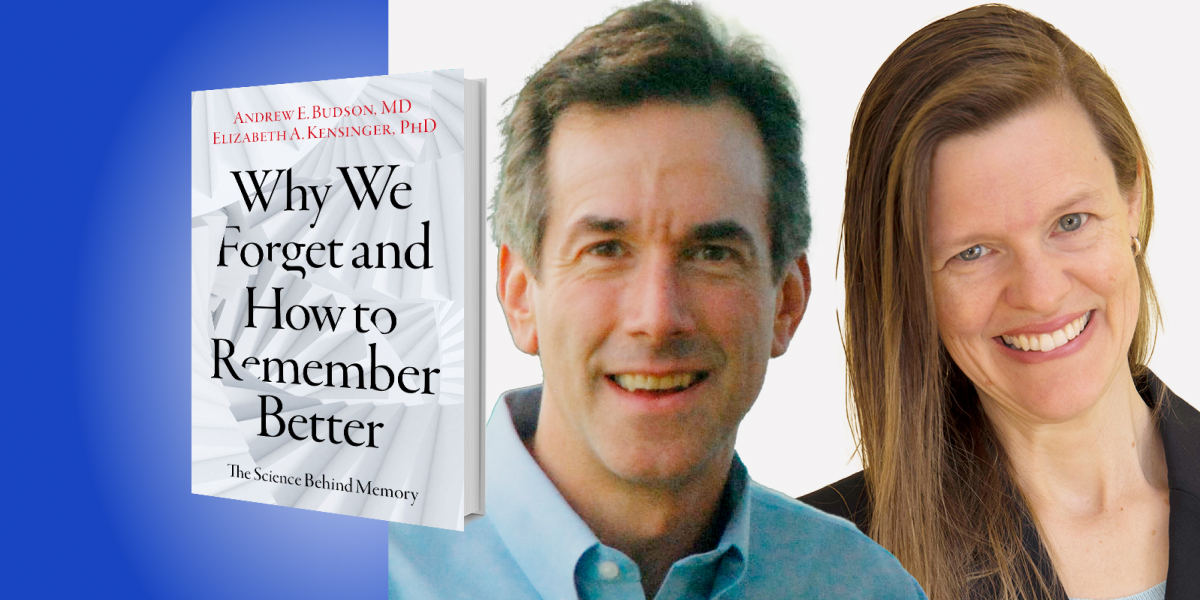

Andrew Budson is the Chief of Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology at the Veteran’s Affairs Boston Health Care System and Professor of Neurology at Boston University.

Elizabeth Kensinger is a professor and Chair of the Department of Psychology & Neuroscience at Boston College.

Below, Andrew and Elizabeth share 5 key insights from their new book, Why We Forget and How to Remember Better: The Science Behind Memory. Listen to the audio version—read by Andrew and Elizabeth—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Memory is not one thing.

In the clinic last week, I saw one of my patients who has Alzheimer’s disease. She is the grandmother of three children and five grandchildren, and has been living with the disease for a number of years. At the appointment, her daughter asked me a couple of very good questions: How can she still play piano—and play it well—when she can’t remember her own grandchildren? How can she still remember all the recipes she used to cook when she was growing up, when today, she can’t even remember whether we went to the grocery store an hour later?

The answer is that memory is not one thing. Alzheimer’s tends to affect some types of memory more than others. Episodic memory is your memory for events or episodes of your life. It’s the type of memory that you use to travel back in time and re-experience a prior event such as the birth of a child or a trip to the grocery store. To play piano, ride a bike, or tie your shoes, you use your procedural memory, your memory for skills and habits. To remember recipes, what color a lion is, or what a fork is used for, as well as other facts and information, you use your semantic memory.

The brain networks used to learn and retrieve each of these types of memories are different, and Alzheimer’s disease generally impairs episodic memory first, then semantic memory second, and only much later does it affect procedural memory. That’s why the grandmother couldn’t remember her trip to the grocery store or even her grandchildren, but she can still recall her old recipes and play the piano.

2. Memory is a cycle.

Memory requires three phases to occur. First, we must have to get the content from an experience into a format our brain can store. We call this the process of encoding. Second, the brain actually has to store or consolidate that information, so that it’s accessible over longer periods of time. Third, we need to retrieve that content in the moment that it’s needed—so we can bring our colleague’s name to mind as they approach. We call memory a cycle because that act of retrieving the memory actually restarts this three-phase process again. We can encode new details—maybe we update our memory of our colleague to note that they now wear glasses—and we must re-store the memory in order for us to be able to access it later. So we are constantly going through that process of encoding and storing and retrieving.

“We call memory a cycle because that act of retrieving the memory actually restarts this three-phase process again.”

Forgetting, and memory distortions, can arise at any of those stages. We can fail to encode a person’s name, or we might encode it incorrectly, as a similar-sounding name. Or, we might encode the correct name and briefly have access to it, but we fail to store it adequately and so later, we’ve either forgotten the name entirely by the time we next see the person or we’ve begun to call them by an incorrect name. We might also simply fail to retrieve the name in the moment it’s needed—leading to the frustrating experiences where we recall someone’s name only after they’re no longer in our vicinity.

3. Forgetting is normal, and can even be helpful.

Do you wish you could simply take a pill and have the superpower to remember everything? Given how much marketing there is for such so-called memory-enhancing vitamins, herbs, and supplements, you might think that if such a pill really existed, you should jump at the chance to take it. But would it really be helpful to remember everything? In fact, why is remembering the past useful at all?

The answer is that your memory for the past is useful because it allows you to imagine the future and plan accordingly. For example, remembering that it rained last week isn’t of much use unless, when you step outside today, you see those dark clouds in the sky, and it reminds you of that rainy day last week, and thus you imagine that it might rain again today. You then go and grab your umbrella.

Memory for the past is useful because it helps you imagine and plan for the future. So therefore, wouldn’t it be helpful to remember everything from your past? Absolutely not. Imagine if your friend asked you where you’d like to go for lunch. Would it be helpful for you to retrieve and re-experience every meal out you’ve ever had? No, you depend upon your memory to forget all those experiences that were quite mediocre, and only remember the ones that were good so you could suggest going to one of them. Of course you also want to remember those restaurant experiences that were quite awful, so that you can make sure that you avoid them in the future. We depend on our memory to prioritize both what we remember and what we forget.

4. There are strategies you can use to avoid forgetting.

During encoding, there are four things that you can focus on doing, using the acronym FOUR.

“Your memory for the past is useful because it allows you to imagine the future and plan accordingly.”

F: Focus your attention on what you want to remember. Don’t multi-task!

O: Organize the information. For example, if you’re a student studying for an exam, don’t try to memorize your notes until they’re organized in a logical way. If you need to memorize your shopping list, organize it by category or in some other way that makes sense to you. Our brain holds onto “chunks” of organized content. The better organized the information, the more we can fit into a “chunk” and thus the more information we can retain. This is why experts can remember so much in their specific domain of expertise; they’ve learned how to organize the information.

U: Understand the information. Confirm you’ve heard the person’s name correctly. Make sure your boss’ request for your next meeting makes sense to you, and only then try committing it to memory.

R: Relate the information to something you already know. Does the person’s name overlap with one of your favorite authors? Make a mental note of that association.

Doing those FOUR things will help you to both encode the information for the short-term and also to get that information stored for longer-term access.

When it comes time to retrieve that information, the fact is, we often thwart our own retrieval attempts. First, we get so anxious, we cannot think of the information that’s stored in our memory. It’s important to try to relax. Deep breaths might be enough, but in some cases you might want to reframe your goal. Don’t worry if you can’t think of your colleague’s name; just reframe your goal as engaging in interesting conversation.

Second, we often think it will help if we generate possibilities for the information we’re searching for. We might think of possibilities for the person’s name, or think of information that might be related to the exam question. Because of the way the brain works, when we retrieve one piece of information, we actually make it less likely that we’ll retrieve related pieces of information. Instead, try to return mentally to the context in which you experienced the information—one of the last times you saw your colleague, or one of the last times you were studying that content for an exam. Memory retrieval works when the brain is able to return to a state similar to the one that it was in at the time of encoding, and bringing to mind that prior context can be one way to help the brain do just that, allowing you to access the content you need when you need it.

5. The most important lifestyle change is to engage in aerobic exercise.

Aerobic exercise releases growth factors in the brain that actually helps you to grow new brain cells. Studies have shown that the effect of exercise is so large that you can actually see expansion in the parts of the brain critical for memory in as little as six months. The increase in exercise correlates with the increase in brain volume which, in turn, correlates with the improvement in memory.

Getting enough sleep is also important. If we don’t get enough sleep at night, then we’re going to be tired the next day, and if we are tired it will be difficult to focus our attention, which we know is critical. In order to hold on to the information that we’ve learned during the day so we can retrieve it days, weeks, or years later, it needs to be consolidated during sleep. If you don’t get a good night’s sleep, you’re going to have difficulty holding onto your memories for a lifetime. That is also why if you cram for that test over a couple of days, instead of studying during the entire semester, that material tends to vanish in a couple of weeks.

“Studies have shown that the effect of exercise is so large that you can actually see expansion in the parts of the brain critical for memory in as little as six months.”

Eating a healthy menu of foods is also critical. In a nutshell, this means eating the Mediterranean menu of foods, including fish, olive oils, avocados, fruits and vegetables, nuts and beans, and whole grains. We can also add poultry, chicken, and turkey. There are some things that we’ve learned are not so good for memory, mainly highly processed food, which includes most snack foods, cereals, and even white flour, white bread, and white rice. Those foods can cause a spike of insulin, which is not good for your brain.

There’s evidence that staying cognitively active by learning new things, staying socially active by spending time with friends and family, and keeping a positive mental attitude are all important. Why would a positive attitude be important? We assume that because people who have a positive attitude are more likely to take care of themselves—by eating right and exercising, and keeping a positive attitude—they are also more likely to be social and outgoing.

Finally, what about those computerized brain training games that they always advertise on TV and radio? Do those actually help? This has been studied, and it turns out that people who spend time working on computerized brain training games get better at those computerized brain training games. However, that doesn’t translate to overall brain health. The things that do are aerobic exercise, eating a healthy menu of food, staying cognitively active, socially active, and having a positive mental attitude.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Andrew Budson and Elizabeth Kensinger, download the Next Big Idea App today: