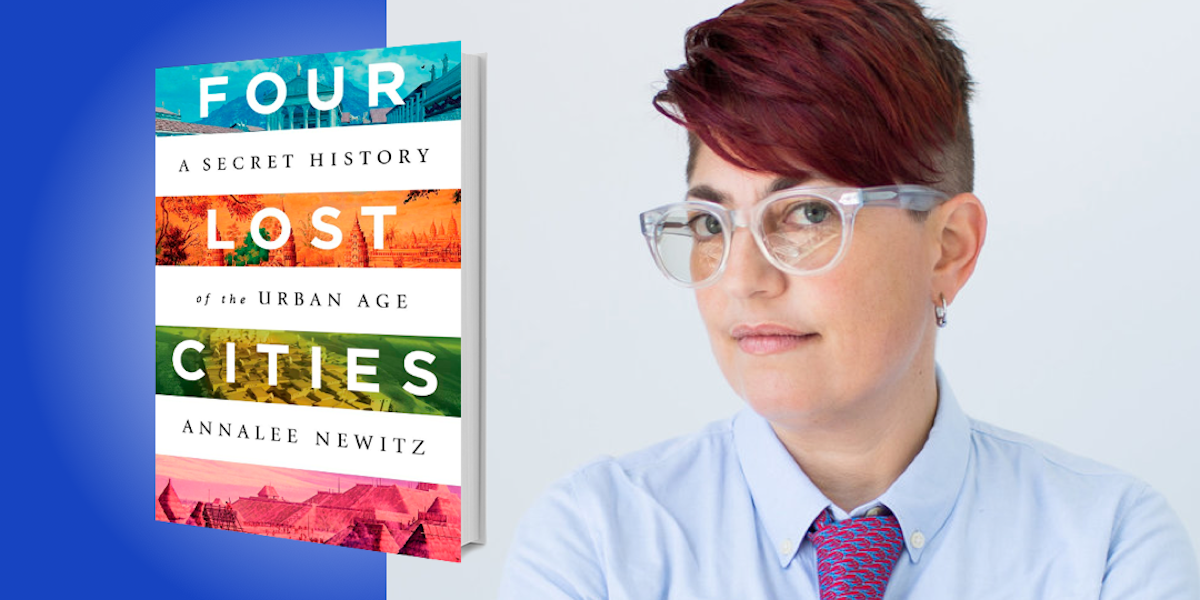

Annalee Newitz, a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times, is a founder of io9 and former editor-in-chief of Gizmodo. They are the author of Scatter, Adapt, and Remember and the novels Autonomous and The Future of Another Timeline.

Below, Annalee shares 5 key insights from their new book, Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. It’s hard to settle down.

About 9,000 years ago, there was a city called Çatalhöyük, located in Central Turkey. Archeologists often call it a proto-city, because it existed at a very important time in homo sapiens’ history. After over 100,000 years of being a species that roamed around and lived in different places during different seasons, we finally started to create permanent settlements. In Çatalhöyük, humans had to reconcile themselves to a strange new form of life; all of their beliefs, ideals, and myths came from a culture that had been nomadic. An archeologist named Marion Benz describes this moment in human history as causing a kind of “architectural crisis.” Humans were trying desperately to build a connection to the land when, before, their connection had been to each other and to the roving bands that they were part of. To help resolve this, they developed a spiritual practice of burying their ancestors and their loved ones under their bed platforms in their homes. Their bones, the bones of their ancestors, became part of this new land.

So if you ever find yourself wondering why it’s so hard to settle down and find a place for yourself, just remember that humans have only been settling down for a little over 9,000 years. For tens of thousands of years before that, we were wanderers—and it’s taken a lot of work, experimentation, and various spiritual and psychological tricks to learn how to stay put.

“Humans have only been settling down for a little over 9,000 years.”

2. Civilization as we know it started in the tropics.

Researchers who have been studying the earliest examples of proto-farms and proto-settlements in equatorial environments—places like the Amazon, Southeast Asia, and elsewhere—have found evidence that starting as far back as 45,000 years ago, people were altering their environment. What ancient people living in the tropics wanted most was food from trees, so they would clear-cut and burn big parts of the forest, and then scatter seeds of trees that they liked. It wasn’t exactly farming, because they weren’t tilling the soil, but they were opportunistically burning and planting stuff that they hoped would come to fruition later. And indeed it did, leaving behind enough evidence that now some archeologists and environmental scientists have concluded that the first humans to reshape the Earth lived at the tropical parts of the planet—instead of Mediterranean places like Mesopotamia, which we had previously believed to be the cradle of civilization.

3. Disaster relief is as ancient as Rome.

You’ve probably heard of Pompeii as the city that was buried in ash by an enormous eruption from Mount Vesuvius. What you probably didn’t know is that Pompeii was a wealthy seaside resort town for Romans—and that over half the city survived that eruption. That’s because it wasn’t a sudden eruption; there were earthquakes and smoke coming out of the mountain, so a number of people safely evacuated to other towns in the Bay of Naples, or back home to Rome. The historian Suetonius tells us that emperor Titus went to the site of Pompeii to tour the disaster scene, and then later took the money from people who died in Pompeii and gave it to the survivors. This meant an incredible transfer of wealth from all of those rich Romans who were taking holidays in Pompeii to the rest of their families.

“People changed the way that they wanted to live—so they changed the way they wanted to build.”

But in ancient Rome, family wasn’t just blood relations—it also included slaves and freed slaves, a group of people called liberti. Often, liberti remained with the people who had been their masters, working for them. And so when Titus reassigned all that money from the people who perished, a lot of it went to freed slaves. Titus also gave money to cities in the Bay of Naples to build new neighborhoods for all the refugees from Pompeii and neighboring cities that had been buried. According to modern historians, Titus’s scheme was an incredible success—it was not just good for people’s lives, but also for the Roman economy. So when you start wondering about disaster relief checks from the government, just remember, this scheme has been working for about 2,000 years.

4. Cities are politics made concrete.

The ancient indigenous city of Cahokia, in today’s southern Illinois, went through many different configurations during its lifetime. In the year 900, when the city was at its height, it was organized on an east/west, north/south grid, with a series of massive pyramids at the center. It looked like modern city blocks, with everything squared off. Most likely, there was a centralized authority or group helping to plan the city and keep everything plumb to this grid. Over time, however, this grid pattern slowly changed into a very different kind of street layout, as people stopped using the centralized pyramid. Many archeologists believe that maybe it was connected to a social movement, perhaps a rejection of an elite class that lived on that mound. Regardless, suddenly we stop seeing signs that people are having celebrations and feasting around the pyramid, and they start using the center as a garbage dump.

“It’s not really ever appropriate to say a civilization has ‘collapsed,’ because as long as we remember it, as long as we study its great achievements, it’s still alive and among us.”

Instead, they began building neighborhoods based around a courtyard pattern, no longer hewing to a rigid grid. They constructed houses in nice circles around big open areas. And then, gradually, those courtyards began to drift further apart, as if the city had broken apart into neighborhoods that became villages. Eventually, people left those villages and moved on to build villages elsewhere. This is how the city emptied out. Not through a massive event, like a huge war or giant catastrophe, but because people changed the way that they wanted to live—so they changed the way they wanted to build. The city didn’t seem like the right place to do it anymore, so they moved on.

5. Civilizations don’t collapse.

It’s very common to hear people talk about the “fall” of Rome or the “collapse” of the Mayan civilization. But the fact is, that’s not how it really works. From studying cities like Angkor and Cahokia that were at the heart of massive civilizations, we learn that it’s not a sudden break—it’s more like a transformation. That’s why most archeologists today prefer to use the term “civilizational transformation” to talk about these moments when people abandon their cities or change their ways of life. The fact is, when people left Angkor, Cahokia, Pompeii, and even Çatalhöyük, they didn’t just discard all those memories and traditions; they took them along to the next place that they would live, and they taught their children about their history. Then the children brought that history with them into the next generation. And so it’s not really ever appropriate to say a civilization has “collapsed,” because as long as we remember it, as long as we study its great achievements, it’s still alive and among us. It’s still influencing us and teaching us lessons.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: