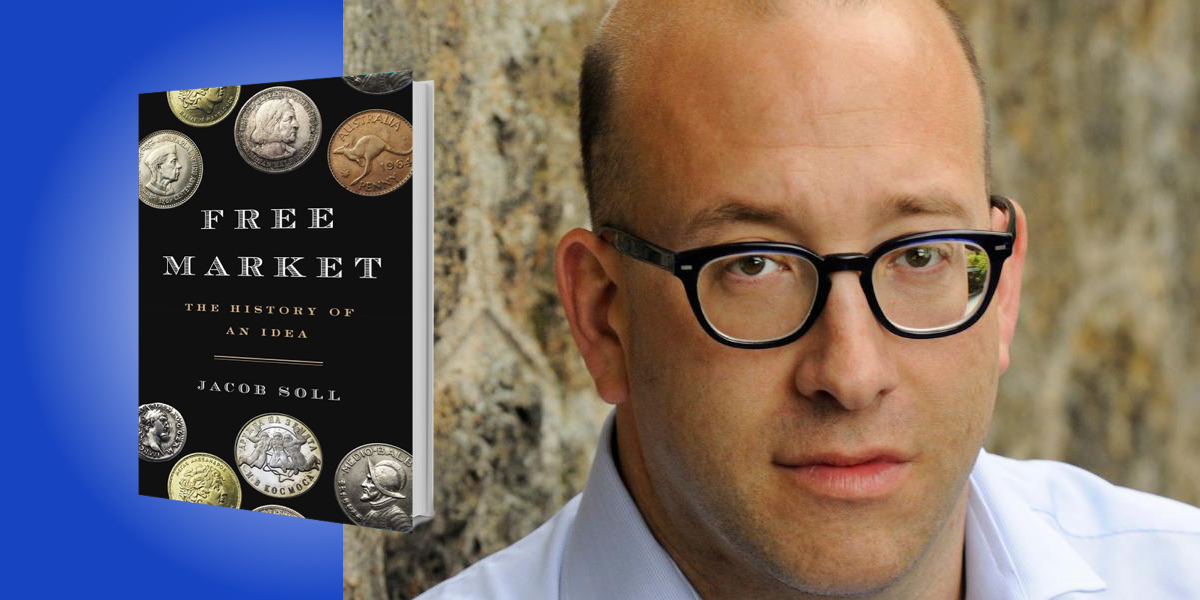

Jacob Soll is an intellectual historian and professor of philosophy, history, and accounting at the University of Southern California. He has been a correspondent for The Boston Globe, and a regular contributor to the New York Times, Politico, the New Republic, PBS, Salon and the Chronicle of Higher Education. He is a recipient of many prestigious awards, including a MacArthur Fellowship in 2011.

Below, Jacob shares 5 key insights from his new book, Free Market: The History of an Idea. Listen to the audio version—read by Jacob himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Cicero’s origin story.

Many people think that free market thought started with Adam Smith, the father of economic philosophy. He was a Ciceronian, meaning that he was a professor of moral philosophy and everything he did harked back to the Roman philosopher and Senator Marcus Tullius Cicero. Since Cicero was the basis for everything Smith did, I started reading Cicero to understand what had Smith so interested in him. I found that Cicero not only had a strict moral stoic code about behavior, but he also had clear ideas on how perfect exchanges between friends (people who care about each other) could create a perfect market.

The first idea of a perfect exchange comes from Cicero. Upon looking through economic texts from the early Christians, to the Middle Ages, Renaissance, Enlightenment, and up through the 19th century, I found that until 1850, almost every major thinker who thought about improving markets relied on Cicero. The traditions that we work with and rely on today run deep.

2. Christians were the first market thinkers.

Christians were interested in replacing Ciceronian thought by arguing that friendship and serving the state will not save a person. Instead, they said one needs to exchange all their wealth—pleasures like sex, food, and material goods—for salvation. The early fathers of the church described salvation as a market exchange that could be perfect. If you’re willing to give up earthly goods, then you can have the treasure of heaven.

“Christians had parted from the Jewish tradition by making faith more transactional.”

This provided a language for economics. In fact, Saint Augustine was the first to use the term an invisible hand—though he doesn’t use it the same way Smith does. The idea was that once you give away your goods and pleasures of your own free will, then the hand of God will bring you into heaven. They say this in relation to Christ too, because Christ exchanged his blood for human salvation in the way a merchant would make an exchange. Christians had parted from the Jewish tradition by making faith more transactional.

From the gospels to the fathers of the church, there was this remarkable language of exchange and markets being expressed in early Christianity. But the first people in the West to look for what we might call market mechanisms (such as supply and demand or the law of diminishing returns) were Franciscans. The Franciscans were monks who took a vow of total poverty, and their fear was that if they broke their vow, then they would be sent to hell. So, they had to understand wealth. They had to understand if a jacket was wealth or if it was just utilitarian. Or if owning books (which was very expensive in the Middle Ages) was a material pursuit or for spiritual study.

Franciscans started studying value and wealth not to become rich, but to protect their own vow of poverty. So, from the gospels to the early Christian fathers to the Franciscans, interest in markets was about poverty. In fact, some of these thinkers were central to scholastic thinkers who would come up with early market ideas about the value of money, and that you couldn’t just assign a value to money. Rather, value of money has to do with how much money is in circulation, and how quickly it circulates. This is quantity of money theory, a major fundamental of market thought. The earliest Christians are at the bedrock of modern economic concepts.

3. Colbert builds a market.

Jean Baptiste Colbert was a French minister of Louis XIV, and he’s considered by economic historians to be the antithesis of free market thought. Well, I am an expert on Colbert after spending 15 years in Colbert’s archives, and I can assure you that Colbert was not against free markets. In fact, he talked about free markets as ideal. But Colbert worried that France was not as developed as its richer neighbor Holland and its neighbor England, and he believed that before France could have free and fair exchange, France would have to develop.

“[Colbert] tried to connect his efforts to the state so that people would trust France on account of its good scientists and therefore trust its products.”

Specifically, he meant that France had to develop an industrial base: weights and measures, roads, transports, commercial laws, and a strong diplomatic corps for trade treaties. So, Colbert started sponsoring science in a time when modern science was being born. He tried to connect his efforts to the state so that people would trust France on account of its good scientists and therefore trust its products. The man who is often portrayed as against free market thought was actually a visionary in what it takes to have functioning, competitive international markets.

4. The first free market reform.

The first person in a government to ever say, “I’m going to liberalize the economy,” was Anne Robert Jacques Turgot. He was a French philosopher of the Enlightenment. He believed in personal liberty, the abolition of slavery, and science.

During his day, France was a feudal country with medieval tolls and taxes that nobles didn’t have to pay. Everything had state oversight, and “the state” included nobles, ministers, and powerful lords. They controlled everything from crossing bridges to using ovens for bread. Turgot’s idea was to liberalize the grain trade. The French were experiencing famines and living on subsistence diets. Turgot said, “The grain trade needs to expand and the only way it can expand is if it’s liberalized,” and he tried his first experiment in the 1760s in a poor region of France. He built poor houses and imported grain for the poor, but he also tried to build industry and make the tax system fair and proportional, so that the entirety of taxes didn’t fall on poor people. He thought that if poor people could get more money, it would spur the economy by inspiring more consumption. Local industry developed so well that the state intervened with their own funding. Turgot’s experiment was successful.

Turgot was also an idealist who put freedom on a pedestal. When he became Controller General of Finance, he moved to Paris and tried to liberalize the grain trade. People warned him that there was a bad harvest and even the grain reserves (held by the state, only to be dispersed as a last resort for keeping people alive during times of dearth) were critically low. However Turgot maintained confidence that by freeing the market, the market would take care of itself.

“Whether one is for or against free market reforms, Turgot was the first to test it—and it didn’t turn out so well.”

Upon Turgot’s freeing of the grain market, there was speculation, shortages, prices skyrocketed, and there was wild inflation. Riots and violence broke out, and France entered what we call the Flour Wars—a pre-revolutionary anarchy. Turgot became convinced that this failure was a conspiracy so he started taking rioters—people of the low and working classes who were starving and unable to get bread—and torturing them, wondering why his system wasn’t working.

The Flour Wars crystallized popular opinion against the state, leading many poor people to organize. Turgot was finally fired two years later, in 1776, with the whole experiment going down the tubes. Whether one is for or against free market reforms, Turgot was the first to test it—and it didn’t turn out so well. However, his first reforms were thoughtful and took into account the needs of society; they were more pragmatic than ideological. There is much to learn from the past that can help us think through the situation today.

5. The strange modern journey of general equilibrium.

Modern free market thinkers want to believe that if you just free the market, it will work. One such thinker is Milton Friedman. He and like-minded peers were deeply idealistic, but they got themselves in bed politically with dark forces. For instance, the proposition that total freedom is connected to segregation. It is an ironic notion for a philosophy based on the very idealistic concept of economic freedom to also go into such dark and strange places.

The bad parts of a philosophy doesn’t mean that it’s all bad, and all parts of the idea should be thrown out, but it goes to show that the ideas we have often evolve in unexpected ways.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jacob Soll, download the Next Big Idea App today: