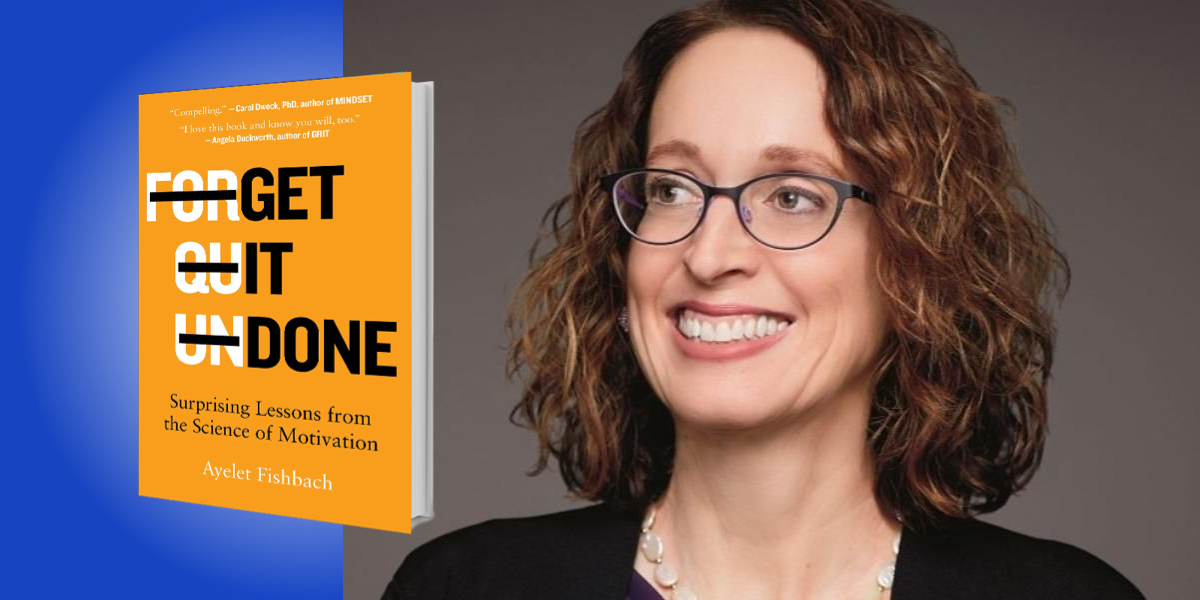

Ayelet Fishbach is a professor of behavioral science and marketing at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. She was president of the Society for the Study of Motivation, and continues to publish her insights into motivation research. Her work has appeared in journals such as Psychological Review and the Journal of Personality, and been publicized through media outlets including CNN, the Chicago Tribune, NPR, and the New York Times.

Below, Ayelet shares 5 key insights from her new book, Get It Done: Surprising Lessons from the Science of Motivation. Listen to the audio version—read by Ayelet herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Set a goal, not a means to a goal.

You might not hesitate to order a $12 cocktail at a restaurant, but you’d drive around the block a few times before paying the same amount for valet parking. You don’t like paying for parking because parking is a means—it gets you in front of the dinner plate you’d set your sights on. Similarly, shipping and gift-wrapping fees are a means to the goal of getting your friend the perfect birthday present. Many of us would rather pay a little extra for the gift and earn free delivery than pay a shipping fee. In general, we want to invest our resources in the goal, not in the means.

This aversion to investing in means can have surprising effects. An experiment we conducted with MBA students showed that people are willing to spend more overall to avoid spending anything on a means. We auctioned an autographed book by a prominent economist. The average bid for the book was $23. Next, we auctioned a tote bag, which contained the same autographed book, to a similarly enthusiastic group of students. Their deal was superior given that the highest bidder would win both a bag and a book. To our surprise, the average bidder was willing to pay only $12—significantly less than what bidders were willing to pay for the book alone. In economics terms, the value of the tote bag was negative, meaning that throwing it in decreased the value of the deal. The reason for this is it didn’t feel right to pay that much for a bag whose only function was to carry a free book.

So when you’re setting goals, try defining them in terms of benefits, rather than costs. It’s better to aim for “finding a job,” rather than “applying for a job.” Achieving a goal is exciting; completing the means is a chore.

2. Find the fun path.

When we find a path to a goal that is fun or interesting, we’re excited about doing it and have a better chance at success; the activity feels like an end in itself. In motivation science, we refer to this activity as intrinsically motivating. Intrinsic motivation is the best predictor of engagement in just about everything. When people are intrinsically motivated, they are more likely to follow through on work tasks, healthy eating, exercising, and New Year’s resolutions.

“When we find a path to a goal that is fun or interesting, we’re excited about doing it and have a better chance at success.”

People often underestimate how important it is to find the fun path to a goal. In one study, we asked people to choose between listening to the song “Hey Jude” by the Beatles and listening to a loud alarm for one minute. Seems like an obvious choice, right? But most of the people in our study chose the loud alarm because it paid more. Yet, those who listened to this terrible noise were also more likely to regret their decision than those who chose to listen to the lower-paying song. While our research participants predicted they would care more about money than sound, they ultimately cared more about sound than money.

Finding the fun path takes several forms. You might watch TV while exercising, or find an exercising activity that is fun in itself. Maybe instead of hopping on an exercise bike, you could play frisbee with friends—or you could just pay attention to the fun that exists in exercising.

3. Broad decision frame.

Detecting the temptations that lead you astray can be tricky, because most temptations are not too damaging if you indulge in moderation. One beer won’t make you an alcoholic, and the one time you left your wet towel on the floor of the bathroom didn’t destroy your relationship. The problem is in accumulation.

You’re more likely to detect a temptation when you make a decision that affects multiple occasions; we call this using a broad decision frame. If you decide in advance what to eat for lunch every day this month, you’ll probably choose healthier foods than if you decide on each lunch each day. Thirty lunch decisions are more consequential than one, so you’ll notice any self-control problems.

Most of us spend too much money on unusual or infrequent items such as hotels or birthday presents, because we tend to consider these purchases one at a time. One study encouraged people to think of these expenses as part of a broad category called “exceptional expenses.” As a result, they were less likely to overspend.

In another study, we asked employees how likely they’d be to engage in questionable work-related behaviors, like calling in sick to take the day off or taking office supplies for personal use. People who thought about taking an unnecessary sick day just one time reported greater intention to actually fake sick. Deciding to go against your moral compass is easier when you consider it as just a single time.

“Detecting the temptations that lead you astray can be tricky, because most temptations are not too damaging if you indulge in moderation.”

4. Make your decisions in advance.

If I offered to give you $120 in six months or $100 now, which would you choose? What if I offered $120 in a year and a half or $100 in a year? Many people would choose $100 in the first scenario, but $120 in the second. Either way, I’m asking you to wait six months for an extra $20. When the options are close, we tend to choose a smaller-sooner reward, but when there’s distance to either option, we choose the larger-later reward.

This example demonstrates one strategy to increase patience: make the decision to wait in advance. According to the advance decision technique, you’ll be more patient if you decide between the smaller-sooner and the larger-later options ahead of time, when they’re both scheduled in the far future. It’s easier to wait an extra month for a better product or a better price when the waiting takes place next year rather than now. Our perception of time is nonlinear—the difference between now and next month seems larger than the difference between one year from now and one year plus one month.

Even pigeons benefit from making advance decisions. In one study, pigeons chose between a small, immediate reward (a peck on a key that produced two seconds of access to grain immediately) and a large, delayed reward (a peck on a key that produced four seconds of access to grain, delayed by four seconds). The pigeons were impatient; they preferred the small, immediate reward. However, when the researchers introduced a constant time delay of ten seconds to both options, the pigeons started pecking more on the key that offered the delayed reward. They had switched their answer to the question, “Are you willing to wait an additional four seconds for more grain?”

We can use this principle to increase patience. All we need to do is introduce more time before the smaller-sooner option becomes available.

“You’ll be more patient if you decide between the smaller-sooner and the larger-later options ahead of time, when they’re both scheduled in the far future.”

5. Do it with others.

Marie and Pierre Curie discovered two elements on the periodic table: polonium and radium. In 1903, the couple jointly won the Nobel Prize in Physics. It was Pierre who insisted that Marie also be named, and Marie won a second Nobel Prize (this time in chemistry) on her own eight years later. Marie and Pierre Curie were able to make such incredible discoveries in part because they did it together. Their story tells us how two people can support each other’s motivation.

We connect to those who hold similar goals. When Marie and Pierre first met, they immediately bonded over their scientific interests. We also help each other’s goals, as Pierre supported Marie by insisting she be named on their Nobel Prize. Helping each other is fundamental to social connection. When you sit at the table each night and ask your partner about their day, brainstorming a polite way for them to talk to their coworker about picking up the slack, you’re instrumental to their career goals.

We also pursue shared goals, and goals that require joint effort glue us together. Marie and Pierre worked tirelessly, day in and day out, as they attempted to isolate polonium and radium. You and your partner may be saving for a house, taking care of a pet, or planning a trip—no matter the goal, you need each other to succeed.

Finally, we hold goals for other people, and they hold goals for us. Marie and Pierre Curie wanted their two daughters to do well in school. We assume they cared mostly about science, which could have prepared their oldest, Irène, to win her own Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1935. Irène, too, won with her husband, with whom she was working.

To listen to the audio version read by author Ayelet Fishbach, download the Next Big Idea App today: