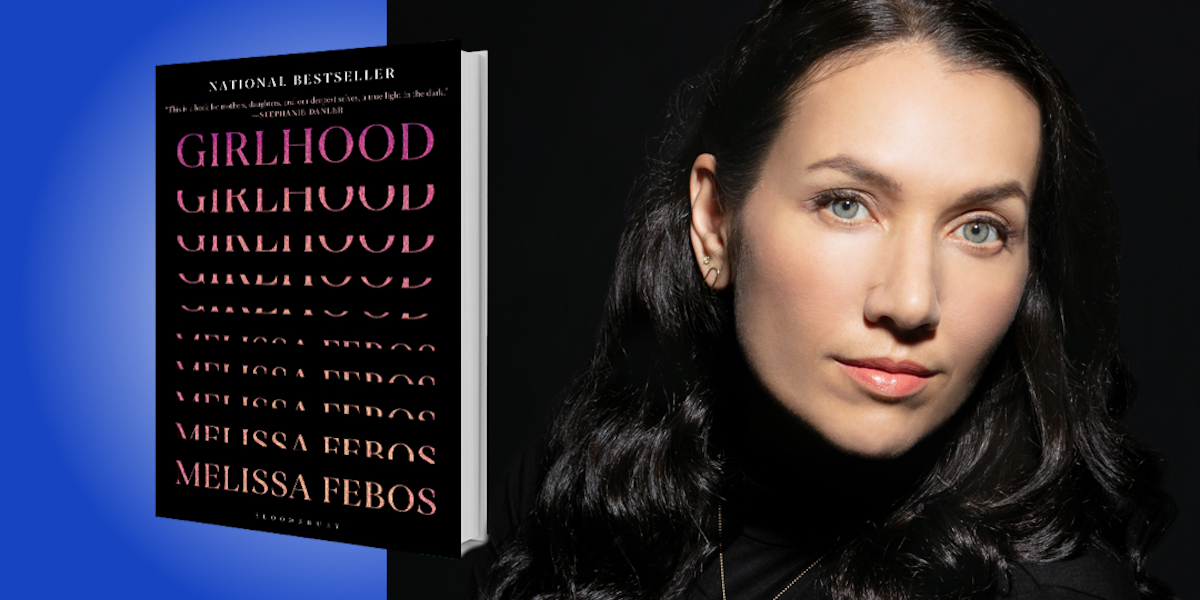

Melissa Febos is the author of three books and a professor of creative writing at the University of Iowa. She is the inaugural winner of the Jeanne Córdova Nonfiction Award from LAMBDA Literary, and her essays have appeared in The Paris Review, The Believer, McSweeney’s Quarterly, The New York Times, and more.

Below, Melissa shares 5 key insights from her new book, Girlhood (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version of the book bite—read by Melissa herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Girlhood is harder than we think.

I felt ambivalent about the title Girlhood for a while. The word “girlhood” conjured images of pink things, tutus, dolls, innocence—a kind of idyllic sweetness that would belie the contents of the book I’d written. But over time, it grew on me. Why should the word for female youth convey a hopelessly idealized conception of our experience? We can change what words connote. I want to bust open the word “girlhood” so that it can hold more of our true stories, because girlhood is harder than we think.

2. Empty consent.

Empty consent is a term I came up with to describe when a person consents to touch she doesn’t want, or feels ambivalent about. In contemporary discourse around consent, the emphasis is on saying yes or no. And it is important that we give people the chance to say yes or no to sexual contact, or any kind of contact. But what happens when our bodies say no and we say yes? I never really thought about this until I went to my first cuddle party. Do you cringe at that idea? So did I when my friend sent me a link to register for the event, which sounded basically like a cuddle orgy. I had such a strong reaction to it that it made me curious—so I went.

“I’d been doing it my whole life—consenting to all kinds of touch I didn’t want because it felt rude not to.”

There was a lot of emphasis on consent at the cuddle party, which was great. The whole first half was basically a workshop in affirmative consent wherein we were partnered with strangers and had to role play asking each other to cuddle and then saying no. The hosts instructed us to respond to no with the phrase “thank you for taking care of yourself.” Then it was time for the cuddle orgy. When the first person, a perfectly nice stranger, asked me to cuddle, I didn’t really want to, but it felt rude to say no, even after the role play. This happened a few times during the event. Afterwards I felt horrible, and I wondered why I’d done that. Then I thought back over the years since my adolescence, and I saw that I’d been doing it my whole life—consenting to all kinds of touch I didn’t want because it felt rude not to. I was shocked and not shocked, as we are when a thing right in front us suddenly becomes visible.

We live in a society that has historically valued men’s desire over the bodily sovereignty of women. It wasn’t until a thousand years after Christ’s birth that a pope decreed that the bride, not her father, ought to be the one who said, “I do.” Marital rape wasn’t a nationwide crime in this country until 1993. We know how common sexual assault is—about one in four women experience it—but I’ve not found research on how often we are touched by men without our consent from childhood: belly and cheek pinches, shoulder squeezes, hands on thighs, unwelcome hugs, the hand of a passing stranger in a bar grazing our back. We are trained to tolerate touch whether we want it or not.

It was clear to me how that long history had reinforced itself. Years of tolerating touch I didn’t want had made it possible for me, a 37-year-old feminist and college professor, to submit to cuddling a stranger I didn’t want to cuddle. After I realized for how long I’d been consenting to touch I didn’t want, I spoke to more than 30 other women, and they all had experienced it their whole lives. How had we not talked about this?

Well, one explanation is that there were literally no words for it; it was so ordinary, we all just took it for granted. We can’t change something until we name it. So, I did: empty consent.

“I never wanted to be a delicate flower; I was always a baby tiger.”

3. Words matter.

This seems like an obvious idea, especially for a writer, but it took me a long time to internalize in some ways.

Over the years, when I would tell a friend about, say, flirting with someone, or a sexual exploit, that friend would tease me by saying, “you slut.” I would laugh, but inside, something churned. Sometimes I would simply overhear a friend say it to someone else, “Good for you, you slut!” Same churning. I tried to ignore it.

You see, I spent a year of my adolescence (6th grade, when I went from 12 to 13) relentlessly harassed by my peers. Today we call it slut shaming or sexual harassment, but I had no words for it then. It was hell, and I never really spoke about it to anyone. I felt like I had brought it upon myself, by having the wrong body, or not feeling able to stop some of my early sexual experiences despite wanting to.

4. Baby tigers and the importance of perception through oneself.

I once hated my own body, especially my hands. I think most of us have at least one part of our bodies that we have a fraught relationship with—some of us would be hard-pressed to choose only one. Mine used to be my hands. I am a pretty small person, but my hands are huge. When I was a kid, this wasn’t a problem—my hands helped me climb trees and catch baseballs and swim and wrestle. I valued my strength. I wanted to be big.

“Just because something is ordinary doesn’t mean it’s not traumatic.”

Then I hit adolescence, and I hated my hands for 25 years. It took a lot of work to undo my early education; I had to free myself from the definitions of femininity that I was indoctrinated with from a young age. Even over all those years of hating my body, I still delighted in my strength. I had to change the framework of my perception away from the one that was prescribed to me by a patriarchal culture, and replace it with one based on my actual experience, my actual values. I never wanted to be a delicate flower; I was always a baby tiger.

5. Little t trauma.

If you had told me five years ago that I’d be publishing a book about the hardships of my girlhood and how they’d influenced the rest of my life, I would have scoffed. I had a happy childhood. I had parents who loved me. I experienced no major traumas. Sure, some things had been hard, particularly around adolescence, but nothing unusual.

I knew people who had experienced trauma. They had lost a parent, or been in a catastrophic car collision. They had been raped. My hardships were just ordinary things—I developed early and was sexually harassed by my peers in middle school. I had a lot of early sexual experiences with older kids that I consented to. I didn’t enjoy them, but so what? I hated my body, but doesn’t every adolescent girl?

As I was writing the essays that became my book, Girlhood, I realized that those everyday experiences had a profound and longitudinal effect on me. They had drastically lowered my self-esteem, and dictated my relationships to my body, food, sex, and other people.

Ultimately, what I realized is that just because something is ordinary doesn’t mean it’s not traumatic. Because we don’t talk as much about those everyday harms, many of us never tell ourselves the truth about them, and we never get to recover from them. Maybe being slut shamed for being the only girl in class with breasts, or having sexual experiences at 12 and 13 that weren’t pleasurable, isn’t on the same level as being raped or losing a parent—but it is analogous. It can define who a person becomes. So, let’s make a distinction: It’s not a capital T trauma, but a little t trauma. Now, we talk about it. Now, we can face how it’s defined us. Now, we can free ourselves from it.

To listen to the audio version read by Melissa Febos, download the Next Big Idea App today: