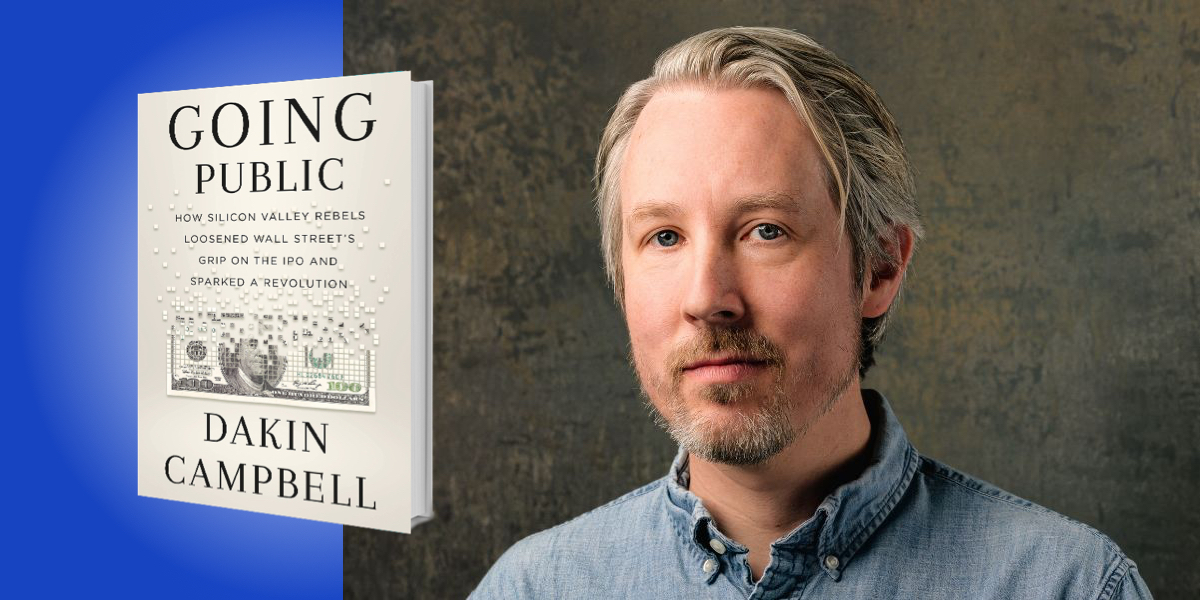

Dakin Campbell is the chief finance correspondent at Business Insider. He has been a journalist for more than 15 years, having previously reported on behalf of Bloomberg, Businessweek, and Markets.

Below, Dakin shares 5 key insights from his new book, Going Public: How Silicon Valley Rebels Loosened Wall Street’s Grip on the IPO and Sparked a Revolution. Listen to the audio version—read by Dakin himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Know your material.

For decades, Wall Street investment banks controlled the way private companies listed their shares on an exchange for the first time—known as an initial public offering. The modern playbook requires that banks act as middlemen between companies selling shares and the investors buying them. Acting on both sides, the banks are inherently conflicted and there have been attempts over the last few decades to rewrite the rules. It wasn’t until Spotify’s top finance executive, a man named Barry McCarthy, found a way for Spotify to list its shares on an exchange without having to issue new stock that technology startups finally got the upper hand. Soon other executives, like Stewart Butterfield at Slack, Kim Jabal at Unity, and Prabir Adarkar at DoorDash, followed McCarthy’s lead. They were helped in no small part by advisors like venture capitalist Bill Gurley and IPO guru Lise Buyer. The story of how they beat adversity and a system stacked against them holds universal truths.

A critical piece of groundwork for this revolution came from Barry McCarthy, a lifelong student of the financial markets. Twenty years earlier, McCarthy had been an incoming executive at Netflix when he popped a tape into the dashboard of his Ford Explorer. Driving cross country to Netflix’s headquarters from Princeton, New Jersey, McCarthy listened to a lawyer explain the inner workings of the IPO process. The crash course was just one of many times McCarthy took an extra step to learn the market mechanics.

“The story of how they beat adversity and a system stacked against them holds universal truths.”

His interest never wavered, so when he became Spotify’s CFO, he had the curiosity and self-knowledge to come up with something different. As he spoke to lawyers and bankers, McCarthy was frequently met with skepticism. It was only through his deep knowledge of the topic that he was able to face down the doubters and stick to his plan. Spotify’s board leaned heavily on McCarthy’s expertise and eventually agreed to let him forge ahead. If it wasn’t for McCarthy’s complete command of the topic, Spotify would never have ignited the wave of innovation that came after it.

2. Question the conventional wisdom.

It can be hard to be critical of what’s currently popular, but it’s often exactly what’s needed to come up with a business breakthrough. As a research analyst on Wall Street in the 1990s, Lise Buyer developed a reputation for voicing what other people were afraid to say. She was outspoken about the prices being paid for Silicon Valley startups. At one point, Buyer even refused to follow the convention of putting price targets on technology companies because their unproven business models and the boom-market psychology made it too hard to predict. When the market came crashing down in the early 2000s, her caution was proven out.

Buyer moved over to Google, where she served as one of the chief architects of that company’s unconventional IPO, before starting her own firm to advise startups on the IPO process. A couple years ago, she helped a company called Unity Software reimagine key parts of the IPO. Throughout her career, Buyer frequently chose to ignore the well-trodden path in favor of following her own trajectory. That’s a big reason why she had a hand in rewiring how companies approach financial markets.

3. Make your voice heard.

It can feel risky to raise your voice in a meeting or stand up publicly for something you believe in. That didn’t stop Bill Gurley. Like McCarthy and Buyer, Gurley had grown frustrated with the traditional mode of selling shares to the public. But he wasn’t a corporate executive and he didn’t have a presence in board rooms across Silicon Valley. What the venture capitalist did have was a reputation as one of the world’s most successful startup investors, a Twitter following in the tens of thousands, and an open invitation to appear on cable TV business shows.

“Even if they didn’t choose it, executives now had permission to ask their bankers for alternate ways of listing shares.”

Over the course of an 18-month period, Gurley criticized the traditional IPO process, almost single-handedly bringing the issue to the top of the agenda in Silicon Valley and on Wall Street. When he further channeled those frustrations into a one-day symposium organized for startup founders and other venture capitalists, Gurley’s command of the narrative was nearly complete. From then on, dozens of startups thinking about going public asked their investment bankers about the model that Spotify pioneered. Even if they didn’t choose it—only 13 companies have—executives now had permission to ask their bankers for alternate ways of listing shares. Those conversations likely wouldn’t have happened without Gurley’s adept use of his megaphone.

4. Follow through on your plan.

In the face of doubters, it can be hard to stick to your plan. But that’s exactly what Kim Jabal, the former finance chief at Unity Software, did when she put her own stamp on the IPO. An ex-employee at Google and a longtime tech executive in Silicon Valley, Jabal was a passionate believer in using data to drive decisions.

When it came time to take Unity public, Jabal worked with her CEO and Lise Buyer to collect an extra amount of data. One of the things she focused on was the process of handing out shares to certain types of investors. Conventional wisdom said that companies needed to give a percentage to those who would sell the next day, helping to make a market for the stock. However, the data showed that it was hard to discern which investors will hold and which will sell. If the share price surged on the first day of trading, investors who sold would make an easy profit. Jabal decided to apportion a much smaller amount to investors whom she expected would sell.

“Jabal was a passionate believer in using data to drive decisions.”

The decision made Jabal’s investment bankers anxious and they pushed her to give more to investors who might sell. She stuck to her conviction and the company enjoyed a successful offering. If Jabal hadn’t followed through, Unity wouldn’t have established a model that was used by numerous startups after it.

5. Know when to end your experiment.

Lots of management experts suggest taking small risks to see if they work out. But how do you know when to pull the plug on an experiment that isn’t working? Airbnb, the home sharing company, was facing that decision in the summer of 2020. The CFO, Dave Stephenson, had persuaded the board to go forward with a similar transaction as Spotify’s. The process would have made Airbnb the first company to do that type of listing on the Nasdaq, making Airbnb a pioneer in its own right. The company wouldn’t have raised any money—which would have been fine. Airbnb didn’t need it. But then came the pandemic, travel dried up, and Airbnb hemorrhaged cash.

Stephenson, who is practical and unemotional, saw the reality and changed Airbnb’s plans. Instead, the company would do a traditional IPO. When it went public in December of that year, the transaction raised $3.5 billion and gave Airbnb the money it needed to weather the pandemic. When the experiment looks like it might imperil your company, Airbnb’s story suggests that it’s okay to end it.

To listen to the audio version read by author Dakin Campbell, download the Next Big Idea App today: