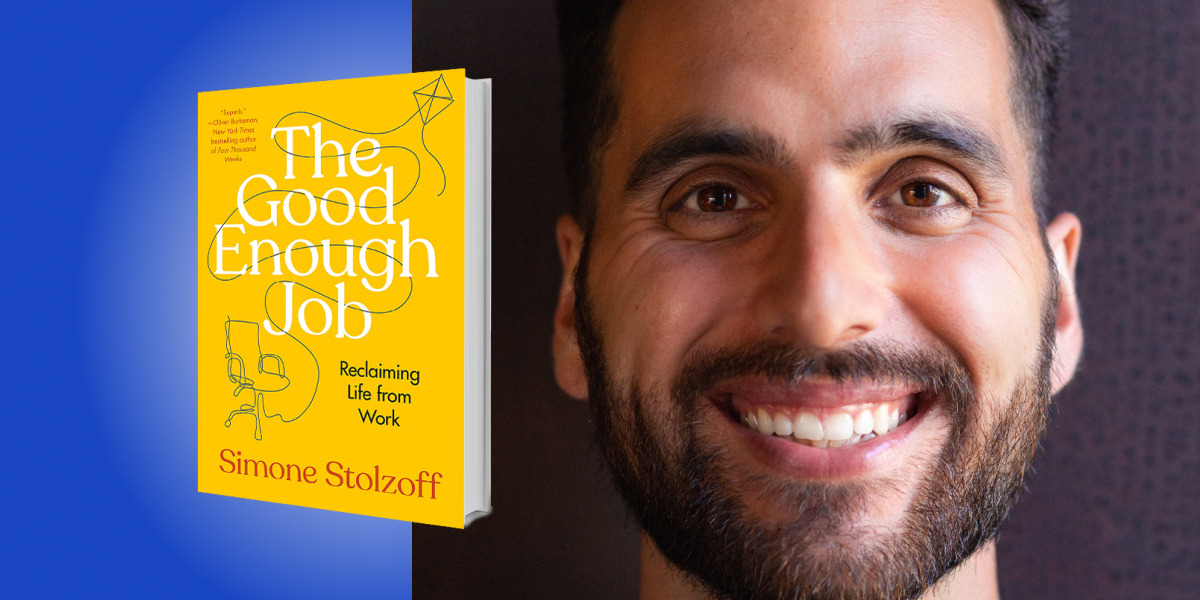

Simone Stolzoff is a writer, designer, and work expert whose work can be found in the New York Times, Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and The Atlantic, among others. He is also a former design lead at the global innovation firm IDEO.

Below, Simone shares five key insights from his new book, The Good Enough Job: Reclaiming Life from Work. Listen to the audio version—read by Simone himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Intrinsic motivation tends to be more fulfilling than extrinsic motivation.

In one of the most famous psychological experiments on motivation, researchers observed how students at a local preschool spent their free time. After identifying which kids chose drawing as their activity, they divided the young artists into three groups. One group was shown a good player award and was told that if they drew, they would receive an award. Group two wasn’t shown an award, but if the students chose to draw, they were given an award at the end of the session. Group three was not shown or given any awards.

Two weeks after the experiment, the researchers returned to the classroom to observe the students again. The students in groups two and three drew just as much after the experiment as they did before. But students in the first group, those who expected to receive an award, now spent less time drawing. It wasn’t the presence of the award, but the expectation of receiving it that dampened the student’s interest in drawing. The researchers concluded that internal satisfaction from an activity may decrease with the promise of an external reward. The experiment has been replicated many times to other students and adults, yielding similar results.

Working for intrinsic validation alone like a high salary, fancy title, or an award is less sustainable than pursuing work you enjoy. The experiment proves something we all intuitively know. Working exclusively for external rewards rarely brings lasting fulfillment. As the old saying goes, How much money is enough, Mr. Rockefeller? Just a little bit more.

2. Valuing time tends to be more fulfilling than valuing money.

In the mid-1970s, the average American, German, and French worker all worked roughly the same number of hours per year. In the developed world, average working hours had fallen for most of the 20th century, thanks to technological advancements, labor organizing, and increases in wealth. Historically, the richer a person or a country becomes, the less they work because they can afford not to. But in the mid-1970s, a strange trend occurred in the US. While the average workers’ hours in our peer nations continued to decline, the average American working hours flatlined, and some American workers (namely college-educated men) started to work more than ever.

“Historically, the richer a person or a country becomes, the less they work because they can afford not to.”

Rather than trade wealth for more free time, as was customary for most of history, American elites started trading their free time for more work. It’s well documented that increasing your wealth can increase happiness to a point, but once our basic needs are accounted for, prioritizing time outweighs prioritizing wealth. Thinking about work’s role in your life, especially if you’re relatively well off, it’s worth considering that valuing more free time over more money tends to be more fulfilling and lead to higher overall well-being.

3. Satisficing tends to be more fulfilling than maximizing.

Imagine you’re buying a sweater and you find one that fits well and looks good for a fair price. If you’re what social scientists call a maximizer, you might ask the clerk to put the sweater on hold so you can spend the rest of the day checking other stores to see if there is a better sweater out there. If you’re a so-called satisficer, which is a portmanteau of satisfy and suffice, you’ll likely feel content buying the first sweater and moving on with your day.

A satisficer determines their criteria and stops searching once they find something that meets their standards. Whereas maximizers want to be sure that every decision is the best decision possible. In the words of psychologist Lori Gottlieb, the satisficer is the one who wants what she has, and the maximizer is the one always chasing what she wants.

“Many of us have internalized the message that there’s one dream job for us and we shouldn’t stop until we find it.”

While there are benefits and drawbacks to each approach, the research suggests that satisficers tend to be happier. Even if the maximizer exhausts all the options and returns to the store to buy the original sweater, they tend to be less fulfilled than the satisficer who bought the sweater right away.

From a work perspective, many of us have internalized the message that there’s one dream job for us and we shouldn’t stop until we find it. We tweak our resumes and browse LinkedIn in the hopes of finding a role that helps us self-actualize. But perhaps a satisficer approach, where we first determine what matters and then recognize when we have it, is a better recipe for happiness.

4. Define what good enough means to you.

I named my book The Good Enough Job as a nod to the satisficer approach to job seeking. Compared to the perfect dream job, good enough is a more forgiving ideal. It doesn’t idealize what a job can offer, nor accept that work must be endless toil. Fundamentally, good enough is an invitation to choose what sufficiency means to you. Perhaps it’s a job that pays a certain wage, gets off at a certain hour, or gives you the time and energy to do what you love when you’re not working.

The title is also an allusion to a theory by a British psychologist and pediatrician named Donald Winnicott. In the mid-20th century, Winnicott was observing growing idolization of parenting in which parents wanted to be perfect and shield their kids from experiencing any negative emotions. When the kid inevitably felt angry or sad, the parents took it personally. As an alternative, Winnicott proposed the idea of the good enough parent and believed that sufficiency would be better for both the child and parent. The child would learn how to self-soothe and the parent wouldn’t get lost in their children’s emotions.

“Fundamentally, good enough is an invitation to choose what sufficiency means to you.”

The Good Enough Job takes Winnicott’s approach and applies it to our working lives. I’ve observed a growing idolization of work in which people keep searching endlessly for their vocational soulmate, a dream job that will never be frustrating or make them sad. An approach that thinks about what good enough means and then thinks about a job as a part of, not the entirety, of who we are is bound to lead to a more well-rounded and fulfilling life.

5. Diversify your identity beyond work.

If you treat work as your primary source of meaning, identity, community, and purpose, it’s a perilous game. It’s as if you’re balancing on a narrow platform prone to be blown over from a strong gust of wind. We’ve particularly seen this recently in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and layoffs and furloughs across many different industries and sectors. If you treat your job as your primary source of identity and you lose your job, what’s left? This mindset also creates massive expectations about what a job can deliver.

When we live a work-centric existence, we can neglect other parts of who we are. When we are working all the time, it doesn’t just take our best hours, but often our best energy too. Carve out time to do things other than work and fill that time with active forms of leisure. It may sound obvious, but creating meaning in your life requires time and energy. You must do things other than work. Active forms of leisure can take many forms, such as investing in relationships by, for example, setting up a weekly breakfast date with your best friend. It can be finding a hobby that you don’t have to monetize or become an expert at, but it’s simply brings you joy. Or it can be finding a community where an identity beyond who you are in the office is reinforced.

To listen to the audio version read by author Simone Stolzoff, download the Next Big Idea App today: