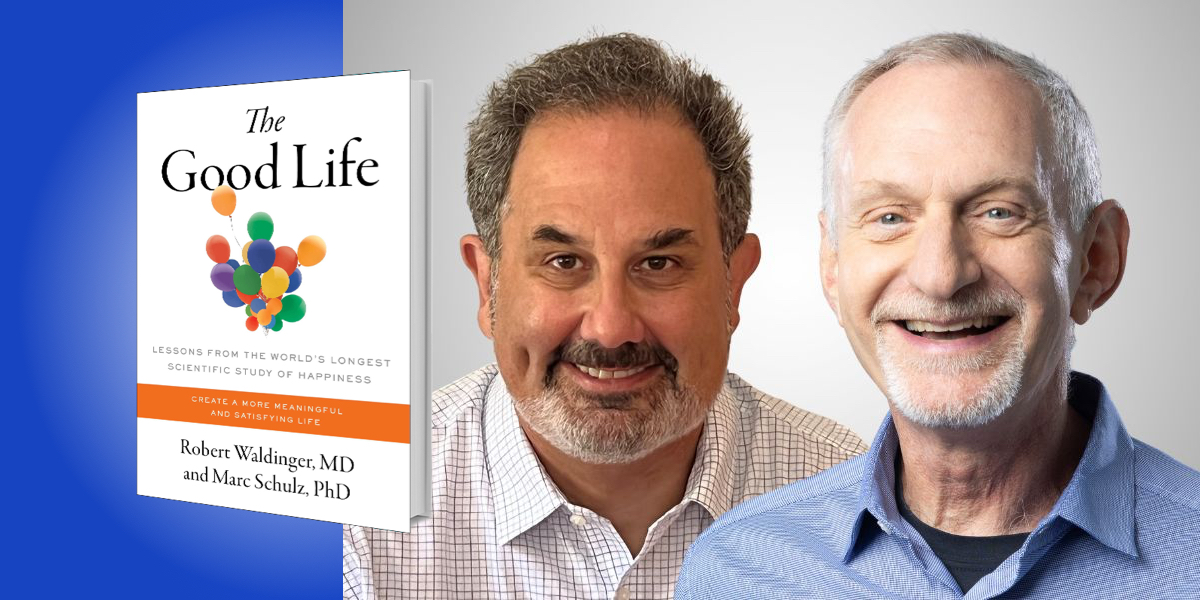

Marc Schulz is a Professor of Psychology and Director of Data Science at Bryn Mawr College.

Robert Waldinger is a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, director of the Harvard Study of Adult Development at Massachusetts General Hospital, and cofounder of the Lifespan Research Foundation.

Below, Marc and Robert share 5 key insights from their new book, The Good Life: Lessons from the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness. Listen to the audio version—read by Marc and Robert—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Relationships keep us happier and healthier across our lifespan, and loneliness erodes our health.

If we step back and look at all 84 years of the Harvard Study and boil the findings down to a single principle for living, one life investment that is supported by similar findings across a wide variety of other studies, it would be this: good relationships keep us healthier and happier, period.

Science also shows us that the absence of good relationships diminishes our health and well-being. People who are more isolated than they want to be find their health declining sooner than people who feel connected to others. Lonely people also live shorter lives. Chronic loneliness increases a person’s odds of death in any given year by 26 percent.

Sadly, this sense of disconnection from others is growing. About one in four Americans reports feeling lonely, and Great Britain has appointed a minister of loneliness to address what has become a major public health challenge. So, if you’re going to make that one choice that could best ensure your own health and happiness, science tells us that your choice should be to cultivate warm relationships.

2. Relationships don’t just take care of themselves, they require active maintenance and renewal.

We tend to think that once we establish friendships and intimate relationships, they will take care of themselves. But like muscles, neglected relationships atrophy.

When the Harvard Study participants reached their 70s and 80s, we asked them if they had any regrets. Many told us they wished they had tended to their relationships more. They talked about friends that they lost touch with and close relatives that they wish they had spent more time with. Lydia at age 78 told us “I wish I’d spent a lot more time with my kids, and less time at work.”

“Unlike stepping on the scale or taking a quick look in the mirror, assessing our social fitness requires a bit more sustained self-reflection.”

Knowing how to improve our social connections—our social fitness—isn’t easy. Unlike stepping on the scale or taking a quick look in the mirror, assessing our social fitness requires a bit more sustained self-reflection.

It requires stepping back from the distractions of modern life, taking stock of our relationships, and being honest with ourselves about where we’re devoting our time and whether we are tending to the connections that help us thrive. It also means asking ourselves what we find challenging in relationships and beginning to make a commitment to doing better.

3. Relationships of all kinds matter, but all relationships come with challenges.

You do not need to be married to reap the benefits of relationships and live a good life. An intimate partnership can bring great joy, but we get benefits from all types of relationships. We can benefit from close friendships, connections with relatives—parents, aunts, cousins, kids—people we work with, and even casual relationships like the person we see on the bus on the way to work or the person who delivers our mail.

The fact is that relationships serve so many functions and help us in some many ways that we are unlikely to get all we need from one person.

While it is clear that relationships are critical for our well-being, many of us struggle with aspects of relationships. This is not that surprising, as relationships are often messy and challenging, and unpredictable. Differences of opinion or preference are almost inevitable in relationships as are feelings of disappointment or vulnerability.

“A good life, in fact, is forged from precisely the things that make it hard.”

Relationships, like life itself, are complicated. They come with joy and challenge—love, but also pain. It is almost impossible to have one without the other. A good life, in fact, is forged from precisely the things that make it hard. Challenges are opportunities for growth. Learning how to navigate relationship challenges better is key.

4. Our attention is our most precious resource.

How should we spend our time and attention? Because of the brevity and uncertainty of life, this is a question that has profound implications for our health and happiness.

There is a Buddhist mantra that that says “If only death is certain, and the time of death is

uncertain, then what should I do?”

Think for a moment about a friend or relative you cherish but don’t spend as much time with as you would like. Now think about how often you see that person. Every week? Once a month? Once a year? You can do the math and project how many hours in a single year you think you spend with this person. Whatever that number is, contrast it with the amount of time that the average person spends today on screens.

In 2018, Americans spent an astonishing eleven hours every day interacting with media, from television to radio to smartphones. From the age of 40 to the age of 80, that adds up to eighteen years of waking life.

“You can prioritize your relationships and choose to be with the people who matter.”

You can decide to whom and to what you give your attention. You can prioritize your relationships and choose to be with the people who matter. By developing your curiosity and reaching out to others—family, loved ones, coworkers, friends, acquaintances, even strangers—with one thoughtful question at a time, one moment of devoted, authentic attention at a time, you strengthen the foundation of a good life.

5. It’s never too late to improve your connections with others.

Andrew Dearing lived one of the most difficult and isolated lives of any study participant. As a child, Andrew’s family moved a lot, and he didn’t develop any lasting friends. His struggles with meaningful connections continued even after getting married in his 30s. When asked in his mid-60s to describe his closest friends in life and what they had meant to him, Andrew wrote simply, “no one.”

When Andrew was 67, he was forced by health problems to retire from a job that was one of the few sources of pleasure and connection in his life. Around that same time, he decided to end his marriage. He was lonelier than ever.

He decided to start going to a gym near his house. Three months later, Andrew knew everyone at the club and looked forward to seeing them when he visited. He also discovered that a few of them shared a love for old movies, and they started getting together to watch movies. When we checked in with Andrew in his 80s we asked how often he left his home to see others or had people visit him. He answered, “daily,” which was quite a change from his answer earlier in his life of “never.”

We live in a world that hungers for greater human connection. Sometimes we might feel that we are adrift in life, that we’re alone and that we’re past the point where we can do anything to change that. Andrew had felt this way, but he was wrong. It wasn’t too late. Because the truth is, it’s never too late.

To listen to the audio version read by authors Marc Schulz and Robert Waldinger, download the Next Big Idea App today: