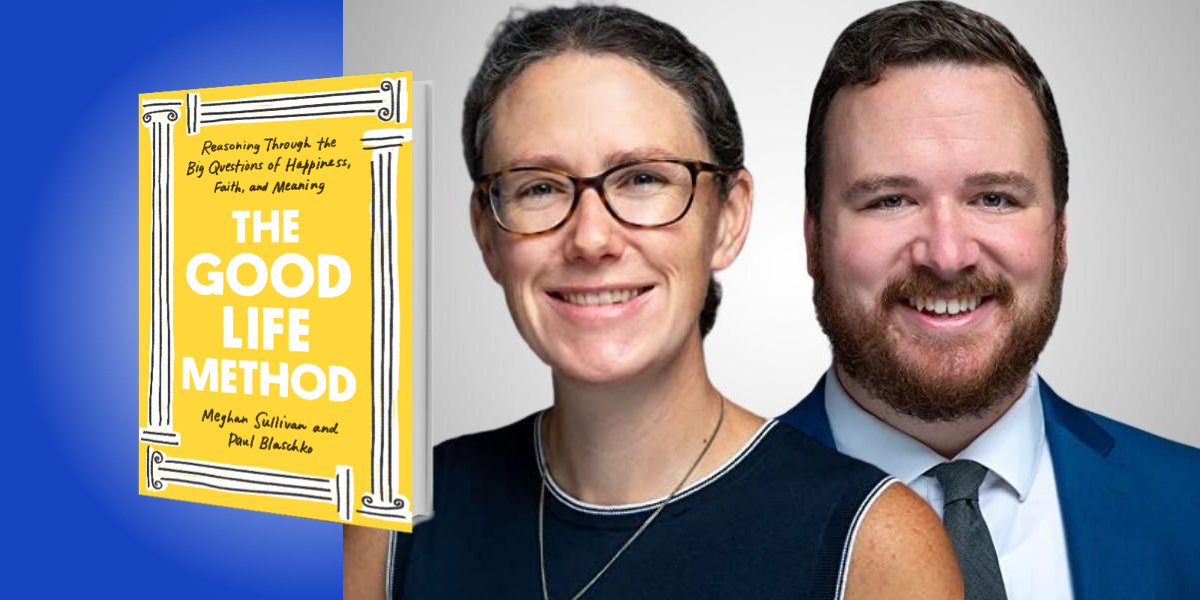

Meghan Sullivan and Paul Blaschko are philosophy professors at the University of Notre Dame. For the past seven years, they have been developing and teaching a course called “God and the Good Life,” devoted to helping thousands of students reflect on, and live, good and excellent lives.

Below, Meghan and Paul share 5 key insights from their new book, The Good Life Method: Reasoning Through the Big Questions of Happiness, Faith, and Meaning. Listen to the audio version—read by Meghan and Paul themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Happiness is more than a feeling.

We all want to be happy, but what exactly does this mean? We often think about happiness as a feeling or emotion—the opposite of sadness. It’s what we feel while we’re watching our favorite movie or eating a delicious meal. This psychological kind of happiness is important, and we certainly can’t ignore it if we’re trying to lead meaningful, contented lives. However, philosophers since Aristotle have challenged us to think about happiness differently.

Suppose a neurosurgeon offered to have a device installed in your brain that would give you a constant feeling of well-being. You’d never stop experiencing something like a runner’s high, or the feeling of being absorbed in your absolute favorite activity. Most of us would probably refuse this offer, and it’s not because we don’t want to be happy. Happiness is a complex state we achieve through years of effort, hard work, and life experience. Some of the experiences that ultimately contribute the most to our overall happiness can feel painful, sorrowful, or even tragic.

If we want to be truly happy in the philosophical sense, then step back and ask about the kind of life we’d need to lead, and the kind of person we’d need to become.

2. You can learn to ask better questions.

A lot of folks are uncomfortable with the idea that we can develop better ideas about big existential “good life” questions. In our deeply polarized times, it can be unnerving to even think about having a conversation with someone else about a complicated moral, political, or religious topic. From the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, we get a model for how to make progress on our beliefs through asking questions we don’t think we know the answer to.

“The skill, as Socrates shows, is learning to love not knowing and getting more skilled at asking.”

Think about two ways questions could be used in conversation. First, there are prosecutor questions—the kind you ask to get someone on the record or expose their beliefs. A vegetarian might ask a meat-eater, “Why don’t you care about animals?” These questions immediately raise defenses and turn philosophical debate into a power game. But there are also dinner party questions—the kind you ask when you don’t know the answer, but want to. You might ask someone with very different food ethics, “When did you realize you had reasons for what you eat?” You probably don’t know what they’ll say, and you’ll learn something about their veganism.

The skill, as Socrates shows, is learning to love not knowing and getting more skilled at asking. This is why he thought the unexamined life was not worth living.

3. Stories can help us become better, more responsible people.

Think about the stories you tell when you’re networking, or meeting someone at a party. There’s a temptation to select these stories for the light they cast you in. To take a simple example: if I’m late for lunch with a friend, I can tell a story in which I’m the victim of unpredictable traffic, when probably the truth is I just didn’t care enough to make sure I left in time. Thinking about the stories we love to tell gives insight into the kind of virtues we are aiming at. If we are reflective about our own “propaganda,” then it also tells us where we are falling short.

Elizabeth Anscombe, a revolutionary figure in 20th-century philosophy, helps explain why stories are so important to our moral lives. She recognized that figuring out what’s right and wrong in a particular situation depends on our motivations, attitudes, and intentions. When my son Solomon hits his little sister, it really does matter whether he meant to do it, or whether it was an accident. Anscombe also helps us see that stories can help uncover the truth about our motivations, and that the ability to tell true stories in all their rich detail—especially when they cast us in an unfavorable light—is an important skill in taking responsibility for our actions, and in learning how to grow our virtue.

“Thinking about the stories we love to tell gives insight into the kind of virtues we are aiming at.”

4. Attention is the key ingredient of love.

“Attention” is not meant as just showering loved ones with gifts, activities, and praise. Attention, for philosophers, means trying to make others a second self—to make their inner narratives and ideas part of your own “good life.” The ancient virtue ethicists say this is a skill of perceiving how someone we love perceives their own life. Contemporary virtue ethicists, like Iris Murdoch, teach it as a skill of looking.

Think about all the ways technology tries to “outsource” love. Maybe we will develop super-intelligent baby monitors that do everything for the infant that new parents typically struggle to manage. It will calm children when they wake in the night, monitor their food and health, and teach them language. We might worry that we shouldn’t develop technology that makes key, loving relationships so detached and efficient. A major part of loving your child is learning to have direct, shared attention that emerges from poopy diapers and late-night feedings. There is also plenty of evidence that the intimacy and vulnerability that predicts stable friendships, and romance, depends on learning to access each other’s minds with attentive questions.

“Attention, for philosophers, means trying to make others a second self—to make their inner narratives and ideas part of your own ‘good life.’”

5. Philosophical contemplation helps us focus on what really matters.

One of the oldest philosophical insights is that a great deal of anxiety comes from being overly attached to things outside of our control. If I make my happiness depend on becoming fabulously successful, wealthy, or powerful, I’ll be vulnerable to the whims of others and to the contingencies of fate. One option is to double down—to try harder to accomplish ambitious goals, hustle more, put in longer hours, try to exert more control. But stoic philosophers, like Marcus Aurelius, remind us that this isn’t the only way.

Stoics encourage the use of reason to constantly reorient toward what really matters. In their view, the most important things in life are virtue and a right orientation toward reality. We always have control over our reactions, and we can respond virtuously to any situation; therefore we can ensure that we’re not attaching our happiness to things beyond our control.

Here’s how this played out in practice for Marcus Aurelius. Suppose something bad happened—he lost a battle, or someone took off with part of his fortune. He would sit down and meditate on the fact that no one can take away his virtue. Material wealth doesn’t make a person good or bad. He even thinks this approach works in the face of our deep anxieties about mortality.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Meghan Sullivan and Paul Blaschko, download the Next Big Idea App today: