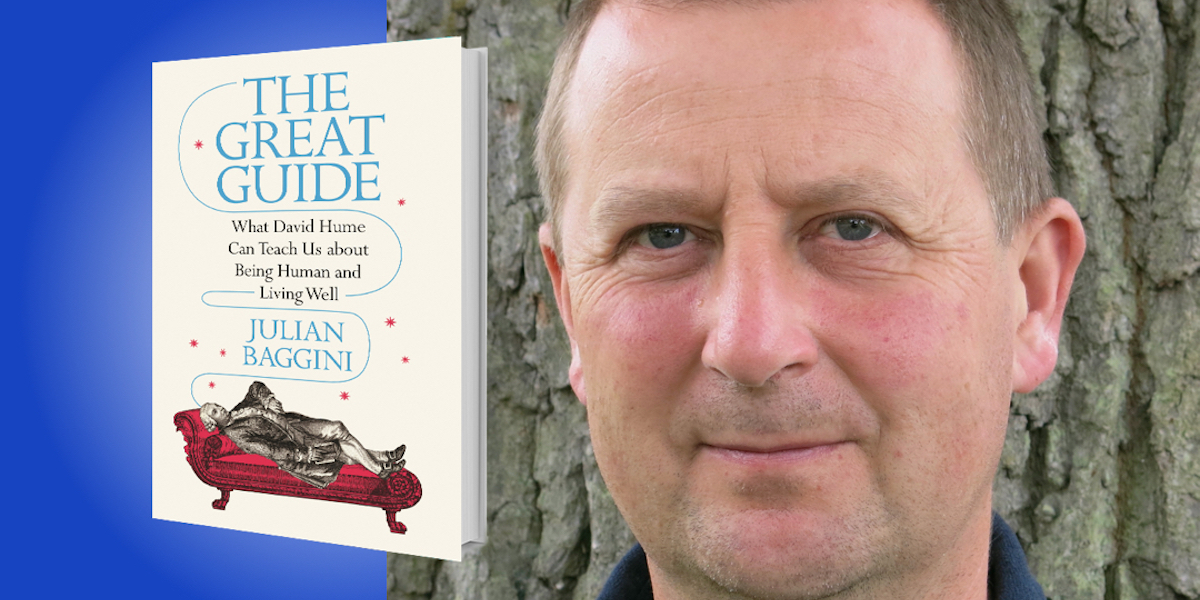

Julian Baggini is an independent scholar, philosopher, and writer. He was the founding editor of The Philosophers’ Magazine and is the author of many books, including How the World Thinks: A Global History of Philosophy and The Edge of Reason: A Rational Skeptic in an Irrational World.

Below, Julian shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Great Guide: What David Hume Can Teach Us About Being Human and Living Well (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Julian himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Be suspicious of big ideas.

Hume had plenty of big ideas, but when it came to understanding politics, society, psychology, and the good life, he was wary of theories that sought to explain everything with a single, simple formula. “To reduce life to exact rule and method is commonly a painful, oft a fruitless occupation,” he once said.

He saw that people often go dangerously astray when they overreach intellectually, and that to become enraptured by the perfection of our ideals is a sure route to error and arrogance. On religion, he said: “What so pure as some of the morals included in some theological systems? What so corrupt as some of the practices to which these systems give rise?”

We do need big ideas, but we need to stop the big from becoming too big. We take ideas that explain a lot and imagine that they explain everything. For example, eating less sugar becomes not good nutritional advice, but the secret to good health. Or mindfulness becomes not a practice that many people find beneficial, but one that you should feel bad for not doing.

“If you find yourself believing you have a theory that explains everything, beware.”

When we fall for big ideas, it can be like falling in love—we become so infatuated that our beloved seems perfect. But the inevitable reversion to reality can be painful, and we can end up despising an idea or a person as excessively as we once adored them. In romance, this may be hard to avoid. But in our intellectual lives, it would be better if we never allowed ourselves to get infatuated in the first place, and always remembered that even the biggest ideas are, in the grand scheme of things, small parts of the bigger picture.

So by all means think big, but if you find yourself believing you have a theory that explains everything, beware.

2. Be stoical, but don’t be a Stoic.

Ancient Stoicism has had something of a revival recently, in the guise of what is sometimes called “modern Stoicism.” As a young man, Hume fell under Stoicism’s spell and tried to put it into practice. But in the end, he rejected it. Why?

The problem with Stoicism is that it tells us to place little or no value on anything other than our reason, the only thing the Stoics believed was under our control. To value things external to ourselves is to value things out of our control, and that makes us vulnerable. As Hume summed it up, “Philosophers have endeavoured to render happiness entirely independent of every thing external.” But as he rightly concluded, “That degree of perfection is impossible to be attained.”

It’s not just impossible to attain, but undesirable. The only way to achieve such Stoic serenity would be to dampen all our emotions, good and bad. Many Stoic sayings are useful and powerful, but my own Hume-inspired conclusion is that everything the Stoics said which is true and helpful is not uniquely Stoic—and everything that is uniquely Stoic is neither helpful nor true.

“The only way to achieve such Stoic serenity would be to dampen all our emotions, good and bad.”

3. Be rational, but don’t be a rationalist.

A rationalist is not someone who wants to be as rational as possible, but arguably someone who wants to be more rational than is possible. Philosophers like Plato, Descartes, and Spinoza seemed to think that if we could only reason with pure logical clarity, we could deduce all important truths. To them, reason was even more powerful than experience; in fact, you could prove truths about ultimate reality without leaving your chair.

But Hume would have none of this. He saw that pure reason leads not to certainty, but absolute skepticism. “Understanding, when it acts alone, and according to its most general principles, entirely subverts itself, and leaves not the lowest degree of evidence in any proposition, either in philosophy or common life.”

It is experience, not abstract logic, that is the “great guide of human life.” Of course we must use our reason, but we must base it on what we observe. As Hume said: “A correct Judgment, avoiding all distant and high enquiries, confines itself to common life, and to such subjects as fall under daily practice and experience; leaving the more sublime topics to the embellishment of poets and orators, or to the arts of priests and politicians.”

History has shown us many of the great failings of this rationalist approach. Think about modernist architecture—people decided to build houses on the basis of principles that, on paper, looked absolutely brilliant. But too often, the result was buildings that were soulless, that people didn’t like to live in, that created no sense of community.

“It is experience, not abstract logic, that is the ‘great guide of human life.’”

On the other hand, following slightly irrational ideas that seem to work in practice—even when we don’t fully understand why—doesn’t always lead to the very best outcome, but it usually avoids the worst. So the Humean approach is a middle ground. We must base our knowledge on experience, but we can still use reason to work out how to make things better.

4. “Reason is, and ought only to be, the slave of the passions.”

To be clear, Hume did not think we should act on our unexamined feelings. “All doctrines are to be suspected, which are favoured by our passions,” he warned, and “Prejudice is destructive of sound judgment, and perverts all operations of the intellectual faculties.”

But the larger point he makes is that without emotion, without desire, we have no reasons to act at all. Cool reason cannot provide us with motivation; it can only help us judge the wisdom of our diverse desires, and help us to achieve the ones we end up endorsing.

One surprising consequence of this idea is that morality is rooted in emotion, not reason. It is not logic that tells us murder is wrong, but the compassion we have for our fellow human beings. The heart without the head often goes wrong, but a head without a heart wouldn’t go anywhere at all.

“The heart without the head often goes wrong, but a head without a heart wouldn’t go anywhere at all.”

5. We should understand as we would be understood.

Hume invites us to be honest about our own limitations and failings, and to be understanding of those of others. In many ways, he took a dim view of human nature, noting wryly: “To a Philosopher & Historian the Madness and Imbecility & Wickedness of Mankind ought to appear ordinary Events.” He hated tribalism of all kinds, saying “When men act in a faction, they are apt, without shame or remorse, to neglect all the ties of honour and morality, in order to serve their party.” So although he was known as “the great infidel” and had no religion himself, he had many clergymen among his friends, and even wrote his early masterpiece, A Treatise of Human Nature, with only the Jesuit monks of La Flèche for intellectual company.

In an increasingly fractional, factional, and polarized world, Hume’s plea to see beyond our differences, even when they are big, is more needed than ever. They capture the spirit of a philosopher who was far from faultless himself, but who Adam Smith described as “approaching as nearly to the idea of a perfectly wise and virtuous man, as perhaps the nature of human frailty will permit.”

To listen to the audio version read by Julian Baggini, download the Next Big Idea App today: