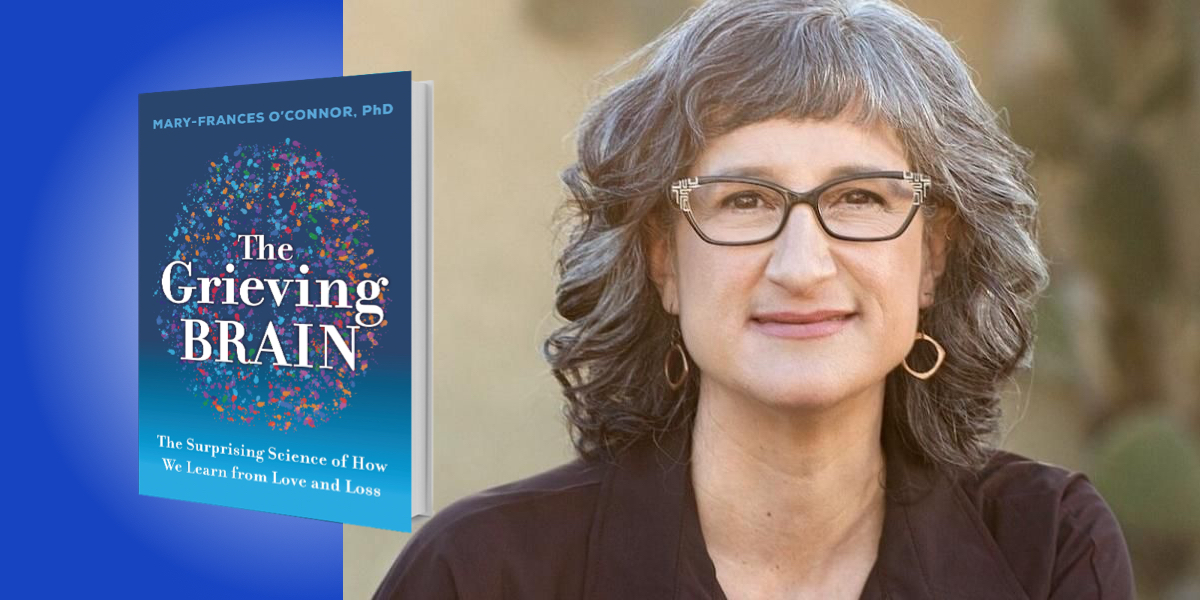

Mary-Frances O’Connor is a neuroscientist and clinical psychologist who directs the Grief, Loss, and Social Stress (GLASS) Lab at University of Arizona. Professionally, she has spent the past 20 years researching the neurobiology of grief. Personally, she experienced losing her mother in her twenties and her father more recently.

Below, Mary-Frances shares 5 key insights from her new book, The Grieving Brain: The Surprising Science of How We Learn from Love and Loss. Listen to the audio version—read by Mary-Frances herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Grief is different from grieving.

Grief is the wave that knocks you off your feet, like being underwater and spun head-over-heels, with the fear that the moment will never end, and you will not survive. Grieving, on the other hand, is how the feeling of grief changes over time without ever going away.

Grieving means that the hundredth time a particular wave of grief sweeps you off your feet, you may still want to escape, but it will also be familiar. You have probably learned by this point that you will survive the moment—horrible as it is. You may have learned how to comfort yourself and give yourself kindness, and begun to acknowledge that you carry a grief that may unleash itself at any time. That change in grief over time is grieving.

If you expect that grieving means you will no longer feel grief, then you will be disappointed. The wave will crash over you in six months, or six years, or six decades after your loved one died. Grief is the natural response to loss, to the awareness that your loved one no longer walks this earthly plane. Grieving means that you will react to these pangs of grief differently over time. And so, grieving takes a long time.

2. For the brain, our loved one is gone and everlasting at the same time.

When our loved one dies, that moment becomes a memory. It could be the memory of watching them decline and being with them at the bedside, or a memory of that terrible phone call that bore news of their death.

“If our loved one isn’t here, our brain believes that they are simply somewhere else, and motivates us to seek them out.”

Memories are but one kind of information that the brain relies on, and there is another stream of information. When we bond with our one-and-only, the encoding of that relationship in the brain comes along with an everlasting belief—the belief that they will be there for us, and we will be there for them. We don’t have to rely on being in their presence for this belief to endure. We could never go our separate ways to work every day if we didn’t have a deep belief that we would come back together again at the end of the day. If our loved one isn’t here, our brain believes that they are simply somewhere else, and motivates us to seek them out, or get their attention so they will come back to us.

But these two streams of information—from our memory and from this attachment belief—conflict. We hear grieving people say, “I know they’ve died, but it just feels like they will walk through that door again any minute.” That is because the grieving brain can hold these two mutually exclusive truths at the same time. The brain has a hard time figuring out how to operate in the world when experiencing two conflicting streams of information.

3. Grieving is a form of learning.

Because our brain is using two conflicting streams of information, we continue to do things like pick up the phone to text our loved one, only to realize that we can no longer do that. These conflicting streams of information mean that it takes a very long time to change the habits we had integrated with our loved one. Psychology defines learning as acquiring new knowledge that enables different behavior. So it isn’t enough to know that they have died—we have to learn a whole new set of habits.

“We know that learning takes time, can be frustrating, and never really ends. In these ways, grieving is the same.”

Our brain is essentially a prediction machine. Its role is to predict what is going to happen next, to help us prepare for it. When we have woken up next to our spouse for thousands and thousands of days, and one morning we wake up and they are not there, our brain won’t readily consider it a likely prediction that they have died. In a sense, for one part of our brain, they haven’t died. It takes many days, weeks, and months of experience for our brain to predict that we will not see them again, and that therefore we need to restore our lives while carrying the absence of that person. We have to learn what it means to us specifically to be a widow or an orphan or bereaved, and what it means for our lives that they have died.

Thinking of grieving as a form of learning may make it more familiar, or make it less scary, because we have been learning from when we were first born. We know that learning takes time, can be frustrating, and never really ends. In these ways, grieving is the same.

4. The would’ve/could’ve/should’ve keeps us from living in the present moment.

I think many people who are grieving will recognize what I mean by the would’ve/could’ve/should’ve. I’m referring to those thoughts that run through your head over and over again, creeping in when least expected, like when you go to bed, or are sitting at a red light. “If only I could’ve gotten them to the hospital sooner, or they would’ve said no to that last drink, or the doctor should’ve ordered another test…”

Here’s the problem with the would’ve/could’ve/should’ve: there are an infinite number of them. Each of those virtual realities we are making up in our head, they each end with, “…and then my loved one didn’t die.” But the painful reality is that they did die. To live in the present moment is to recognize this devastating truth, and what their death means for your life now.

“To live life is to move with all its joys and sorrows.”

The trouble with not living in the present moment is that, although it contains grief and anger and pain, the present moment is also the only way to experience delight and connection and love and silliness and pride. Psychology research tells us that human beings are not able to avoid only negative feelings. If we are avoiding one channel of feelings, then we don’t experience any of them—neither the positive nor the negative. Many people experience this as numbness, or just going through the motions. To live life is to move with all its joys and sorrows.

5. Our brain is forever physically shaped by our loved one.

Bonding with another person, falling in love, physically changes our brain. That bond is encoded literally through sprouting new connections that reach out from one neuron to another, creating new waves of neural firing that pulse across our brain. In research on animals that mate for life, we can see that proteins are folded differently in the brain before and after they bond. This encoding means that our loved one is physically a part of our brain. That physical aspect of them does not go away when they die.

Our brain is different because they loved us and we loved them. Those changes are a physical manifestation of our love, forever allowing us to connect with them through more than memories. If we ask them for advice, in the here and now, we know what they would say, the way they would look at us, and how they would feel hugging us.

I find it marvelous and comforting that the brain does this—creates this physical part of “we” to carry forever. The world is also perceived through our brain, and our brain is shaped by the love we shared, so our world also contains them. We interpret what we see, how we act, and our capacity to love, because our brain carries them forever.

To listen to the audio version read by author Mary-Frances O’Connor, download the Next Big Idea App today: