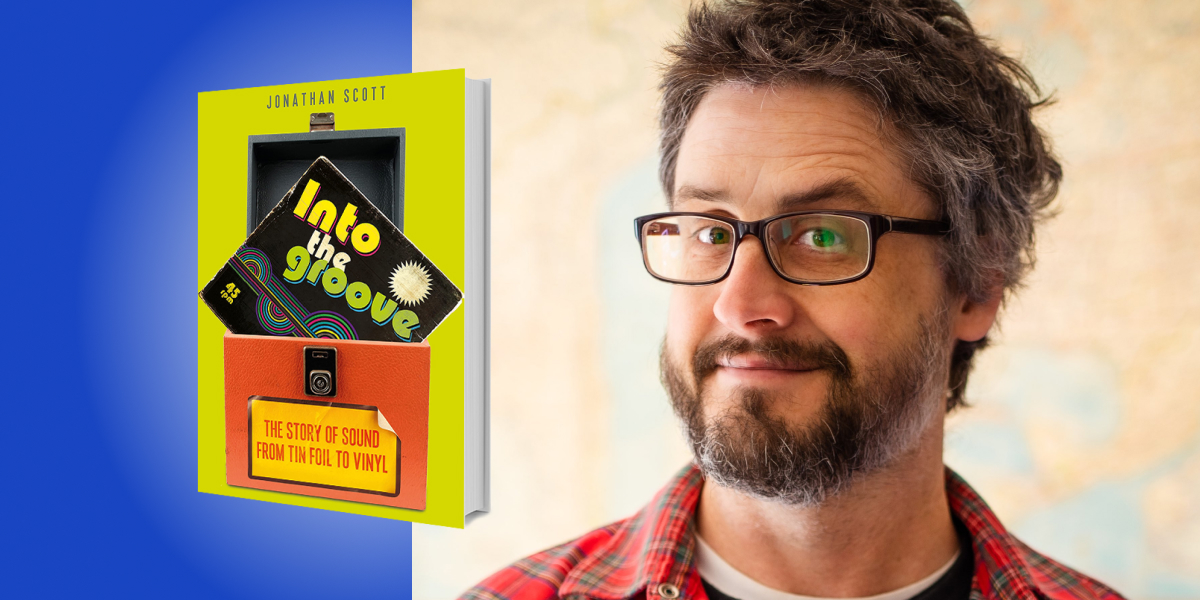

Jonathan Scott is a writer and record collector. Formerly a contributing editor to Record Collector magazine, he has edited books about Prince and Cher and has written about Nirvana, the Pogues, the Venga Boys, Sir Patrick Moore, and Sir Isaac Newton, in a variety of magazines.

Below, Jonathan shares five key insights from his new book, Into the Groove: The Story of Sound from Tin Foil to Vinyl. Listen to the audio version—read by Jonathan himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The past is a fascinating place to visit, and we all can.

This is such an exciting time for anyone with an interest in early sound. This is thanks to the work of pioneering scientists and academics at the likes of Project Irene and FirstSounds.org. Thousands of hours of audio, digitized from the fragile grooves of rare, old, and often unplayable media are available to all. There is the Library of Congress National Jukebox, the First Sounds website, and the Cylinder Audio Archive at the University of California, Santa Barbara, for example, with hours of audio available for free.

If you search “Crystal Palace 1888,” it was recorded on a warm summer’s afternoon in London. There was a Handel festival taking place that summer, and Edison’s UK cheerleader, a mustachioed colonel with a gift for publicity, sat in the press gallery with Edison’s latest phonograph and a box of cylinders. He recorded several thousand voices performing Handel’s “Israel in Egypt.” This is the earliest surviving recording of a live musical performance.

It sounds terrible, like a mic wrapped in a blanket has been dropped in a pond, but that’s exactly what makes it so powerful. You can hear that somewhere in its murky depths is something very beautiful, but far off, inaccessible. It’s like putting your ear to the door of 1888. You can imagine you’re late, hurrying through the park towards the venue, and you can hear the live music you’re missing as you approach.

2. In the 1890s, every record was a one-off.

We’re used to having music at our beck and call, and take it completely for granted. We need to strip away some of the entitlement we all feel around music and revel in the ingenuity of the groove.

“However, to begin with, there was no way of mass-producing a recording.”

The recording industry really got going in the 1890s. Edison’s second-generation phonographs, playing cylinders of wax, slowly transitioned from being office-aid devices aimed at the business community to purveyors of audio entertainment. However, to begin with, there was no way of mass-producing a recording. To sell 100 copies of “The Mocking Bird,” for example, the pioneering hit maker John Yorke Atlee, who was a government clerk by day and a honey-voiced whistler by night, had to record the thing 100 times. Every single copy was its own take. Think of that! Imagine going up to The Cure and saying, “Could I have two, Just Like Heavens and a Boys Don’t Cry please?”

3. Before 1925, all recording was acoustic.

Sound historians divide up popular music into four distinct eras: acoustic, electric, magnetic, and digital. To make a sound recording prior to 1925, there was no volume or tone control. Instrumentalists and singers performed in front of a horn, which funneled sound waves toward a thin diaphragm. In turn, it vibrated an attached stylus, etching sound onto the rotating surface. To make it louder, you sang louder or got closer to the horn. Certain voices, and certain instruments, simply didn’t translate well in the limited frequency range of the acoustic period. Nevertheless, “Caruso 1902,” or “Nellie Melba 1904,” are magic to the acoustic era.

For an interesting before-and-after comparison and contrast exercise, “Rhapsody in Blue, Paul Whiteman 1924,” and “Rhapsody in Blue, Paul Whiteman 1927,” give an insight into the importance of the electric microphone. Suddenly, sound engineers had a fine brush on hand, enabling them to fill the grooves with ever richer detail: voices and instruments unsuited to acoustic recording were thus set free.

4. The first 7″ was pressed in green vinyl.

Many of us think of colored vinyl and picture discs as a modern thing. But, in fact, colored vinyl has been with us right from the start. The modern 33 rpm LP made its debut in 1948, showing off the 20-plus-minute run-time of Columbia’s new micro-grooves. The following year, RCA launched their competing 45rpm 7-inch, kicking off the so-called “War of the Speeds.”

“Colored vinyl has been with us right from the start.”

To start with, they color-coded their releases: country releases were green, children’s records were yellow, classical was red, pop was black, R&B was orange, “international” was light blue, and musicals midnight blue. The very first 45 rpm record was a yellow disc of “Peewee the Piccolo,” pressed on December 7th, 1948. However, the first to be released was, “Texarkana Baby,” by Eddy Arnold in glorious green.

5. Your record collection contains so much more than music.

Records are not only your taste in music, they are a diary, a snapshot of your life, bound up with love, passion, friendship, time, and memory. I write about family history and I’ve come to realize that there is lots of common ground between genealogy and collecting records.

My copy of “Not Fade Away,” by the Rolling Stones is worthless by all modern standards of vinyl collecting lore; it’s so scratched as to be virtually unplayable. To me, it’s priceless simply because it has my mother’s handwriting on the sleeve. It reminds me not only of her, but also of a hilarious conversation, a moment in time, when I was talking to her about her first records, and she described the Stones as “dishy and dangerous.”

So many records have a story: first records, records given for a birthday, records passed on by a beloved aunt, sister, father, or friend, or those bought from a particular place or at a time. These stories are important to preserve; after all, you don’t take your collection with you, you’re just a custodian. One day they will pass on to your family and if you don’t tell someone what the records mean to you, what family stories they represent, they may disappear.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jonathan Scott, download the Next Big Idea App today: