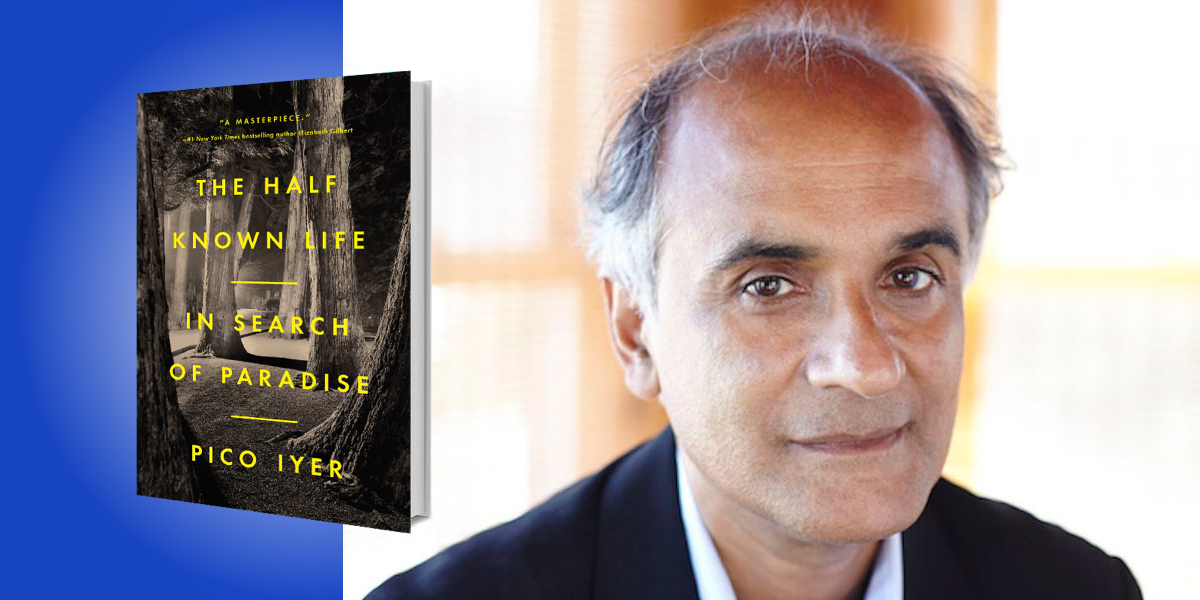

Pico Iyer is an essayist, journalist and acclaimed author of more than a dozen books, translated into twenty-three languages. He is journalism has appeared in Time, Harper’s, the New York Times, The New York Review of Books, the Financial Times, and more than 250 other periodicals worldwide.

Below, Pico shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise. Listen to the audio version—read by Pico himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Sometimes the only paradise we can trust is in the face of death.

Twenty hours after lockdown was declared in California, my mother, then 88, was rushed to the hospital in an ambulance. She was losing blood at a frightening pace. I couldn’t go to see her, since all hospitals were closed to visitors. But as soon as she came home, I took three flights, through ghost-town airports, from my two-room apartment in Japan, to be with her.

As her only living relative, I knew I had to be by her side. As I sat there, for six straight months, I began to think of what my 48 years of crisscrossing the globe had really come to. I also considered how those years might be illuminated by my 30 years of spending time in monasteries, my 48 years of regular talks and travels with the Dalai Lama.

Like all of us, I felt more keenly than ever in 2020 that I was in a world of uncertainty. None of us could say what was going to happen next month, or even tonight. Yet this state of uncertainty was the only home we had. So, my job was to make myself as comfortable as possible within it. As I thought back on all the paradise places I’d seen—from Bali to Tahiti and the Himalayas to Antarctica—I realized that none of them was Eden to the people living there. Even if one were, I might be spoiling it with my very presence, the serpent in the garden.

So, I began to think that the only paradise I could plausibly find was right here, right now, in the midst of the fallen world. “Look beneath your feet,” it says on the ground when you enter a temple down the road from me in Kyoto. We all want a better world, especially at a time of increasing division. Most of us aspire to a better self. But the only paradise I could ever trust was one uncovered in the midst of the real world, and in the face of death.

2. The illusion of knowledge can be far more costly than mere ignorance.

At that point in the hospital, I recalled perhaps the richest and most surprising, sophisticated place I’d ever seen: Iran. As it happens, the country of Iran gave us the word, “paradeiza,” along with some of our most ravishing images of a heavenly garden here on earth.

My first night in Iran, a young local took me to the central shrine in Mashhad, a network of seven interlocking marble courtyards that’s the largest mosque on the planet. When he invited me into the innermost sanctum, where a saint, dead for almost 1200 years, is buried, I noticed my new friend’s hand was on his heart. He was walking backwards, so he never presented his back to the long-dead saint. There were tears welling in his eyes.

“The only paradise I could plausibly find was right here, right now, in the midst of the fallen world.”

When we were back out on the street, he started telling me about his wife, who was, he said, a blonde English woman waiting for him in Yorkshire. He then told me how he had paid a human trafficker twenty-five hundred dollars to smuggle him into Britain in the back of a truck, breathing through a tube so he wouldn’t be detected. He then told me that the British government had given him a court-appointed lawyer and translator, who had worked for three years to win him asylum status.

In other words, he’d risked his life to flee Iran and now he was risking his life, every summer, to steal back into Iran to visit the mosque he missed so much. When he dropped me off at my hotel, I thought of how Iran had been on our front pages every day for as long as I could remember. Yet I couldn’t recall ever reading about a dissident stealing back into the country he’d fled. I also couldn’t remember ever hearing about a deeply faithful Islamic soul who nonetheless didn’t want to live in this Islamic republic.

This was embarrassing to me because I was the guy who had written a long article on Iran for Time magazine, drawing on colleagues’ reports. It was doubly embarrassing because I’d financed my first book with a 20-page article on Iranian history for the Smithsonian. It was quadruple-y embarrassing because I’d once spent four years reading and researching everything I could find on Iran to publish a 350-page novel partly set there, even though I had never been.

Now, within 24 hours of actually visiting, I saw that I didn’t have a clue. This reminded me of how urgent it is to meet our global neighbors in the flesh.

3. Even in the age of information, we often know less about the rest of the world than ever before.

Less than a year after visiting Iran, I returned to North Korea. I knew from a previous visit that a foreigner sees only stage-sets and facades in the Potemkin capital. The glittering skyscrapers are all unoccupied. The friendly locals who greeted me in the showpiece subway cars were actors planted by the government to make a good impression.

In fact, on this trip, I was coming expressly to look at the North Korean film industry. The Pyongyang film studio is three times larger than the Paramount lot in Hollywood.

Yet, the deeper reason to fly back to a city of false fronts is to catch glimpses of a humanity you can’t so easily see on-screen. The government guide who leans forward in the safety of a minivan to ask if Tim Cook’s management style at Apple is different from Steve Jobs’. The local who has seen the world outside North Korea, studying for three years in Pakistan, and asks whether unscripted chaos is really better than micromanaged order. The reminder that even as a visitor, if I so much as folded a copy of a newspaper containing a photo of a flower named after the late leader, Kim Jong Il, I was subject to imprisonment.

“The deeper reason to fly back to a city of false fronts is to catch glimpses of a humanity you can’t so easily see on-screen.”

Often, at home, I’ll pontificate on human reality or universal values. Almost nothing I say begins to apply to the 25 million souls who live in North Korea. Even in the age of information, we often know less about the rest of the world than ever before—and least of all about the countries we hear most about, such as North Korea and Iran. In the age of globalism, it’s easier than ever to be provincial.

4. Just thinking of paradise, or assuming one knows what it is, can get in the way of ever finding it.

For so many across the planet, as in Iran, paradise is essentially a religious concept. So, I began thinking back to the holy city at the center of three great monotheisms: Jerusalem. The first thing that strikes any visitor is that the city of faith is a city of conflict. Not just between the faiths, but within them; Shia Muslim plots against Sunni, ultra-orthodox Jew spits on his secular cousin.

In the church of the Holy Sepulchre, one of the most sacred spaces in Christendom, six Christian orders share the same roof, and go after one another with brooms, or something deadlier, if one of them trespasses by an inch, or a second, on another’s territory.

Yet even I, not a Christian, Muslim or a Jew, find myself irresistibly stirred by Jerusalem. Day after day there, I keep going, almost against my will, to the church of the Holy Sepulchre, just to sit in a little bare rock chapel with nothing to see but a guttering candle. Who knows why, but that small space has an undeniable magnetism. It seems a sanctuary in a world of tumult, beyond all divisions.

“It’s the very belief-systems that promise us unity that actually tear us apart, by stressing that their truth is the only truth.”

It makes me think of the near half-century I’ve spent with the Dalai Lama. He’s one of the most respected religious leaders on the planet, yet he brought out a book that was titled Beyond Religion. So often, he’s seen, it’s the very belief-systems that promise us unity that actually tear us apart, by stressing that their truth is the only truth. Even thinking of paradise, or assuming one knows what it is, can get in the way of ever finding it—or of finding real peace and harmony.

5. A city of death can be a city of joy.

I then recalled another holy city, Jerusalem’s cousin in its way, Varanasi, the center of Hinduism, and of many other spiritual traditions, along the river Ganges. Anyone who’s been there knows that Varanasi is India to the max: the most chaotic, shocking, infernal city in a land of chaos and shocks.

I’m Hindu-born and 100 percent Indian by blood, yet even I am unsettled and sometimes horrified by Varanasi. All along the narrow alleyways, people are carrying dead bodies to the holy river. All day and all night, flames can be seen, to the north and to the south, reducing bodies to bones and ash.

Everywhere, pilgrims are joyfully bathing and gulping down waters that the World Health Organization has declared to be 3,000 times beyond the maximum level of bacteria deemed safe for consumption.

One day, as I stood there, I ran into two Tibetan Buddhist monks I know. They couldn’t stop rejoicing in the scene. “This is the whole human pageant,” said one of my old friends, an American from New York City. “This is the reality in which we have to find our treasure!” All around us, people were radiant with delight as they consigned bodies to the water or the flames.

As it happens, my mother died during the pandemic—though not from Covid—just as I was completing my book on paradise. Of course, it was a shock and a terrible loss. But if someone had told me, when I was in college, that I’d have a parent who’d live to 90, I wouldn’t have believed such a blessing were possible.

A city of death can be a city of joy. A truly sacred place may be one where you no longer make distinctions between sacred and profane. The fact that nothing lasts is the reason that everything matters. Shortly before she died, my mother asked me to scatter some of her ashes in Varanasi.

To listen to the audio version read by author Pico Iyer, download the Next Big Idea App today: