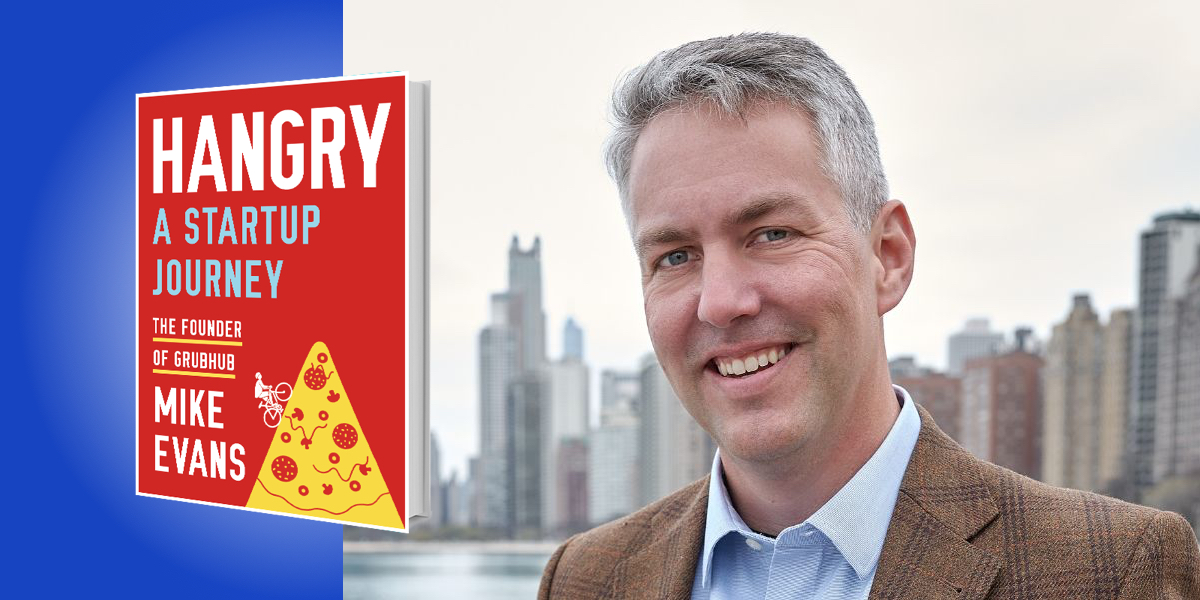

Mike Evans co-founded GrubHub. His new book is Hangry: A Startup Journey.

Below, Mike shares 5 key insights from his new book, Hangry: A Startup Journey. Listen to the audio version—read by Mike himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. You need a personal definition of success.

Everybody around you will try to give you a definition of success. Parents. Kids. Bosses. Churches. Friends. Even society as a whole. Any one of these will gladly spoon-feed you a goal. It’s why many people hate their jobs—they are working toward someone else’s vision, not toward their own. I have a question for you: Who is defining success for you?

I’ve been told I was successful because I founded a company, and I brought it all the way through an IPO. Or people think I’m successful because I made a lot of money in the process. But those weren’t my goals when I started. Don’t get me wrong, it was nice, and for sure, I started GrubHub with financial goals, but the vague idea of “getting rich” wasn’t one of them.

I started GrubHub with a much simpler goal in mind: paying off $260,000 in school debt that my wife and I had racked up. Later on, my definition of success got bigger. I wanted to create a company that leveled the playing field for independent restaurants against the big chains like Dominos and Papa Johns. I was successful because I met my goals, not because I achieved what everyone else thought was important.

2. Achieving success is hard, and that is GREAT.

When we talk about success, we’re talking about something bigger than just a goal. It’s the accumulation of many goals over a long period of time, maybe even a lifetime. The path to success feels more like a drunken stumble than it does walking a straight line. Hitting all those goals, over a time span of years, along with the setbacks that inevitably come along the way is hard. I saw this again and again at GrubHub, so much so that I made up Mike’s rules about hard things.

- Hard things are hard. Satisfaction and achievement don’t cancel out the difficulty. They exist simultaneously and in tension.

- Hard things have consequences. Achieving one set of goals often comes at the sacrifice of another set of goals. We talk about work life balance, but that’s elusive. The reality is that sometimes relationships suffer in service to career. Investing in health takes time, and that conflicts with urgent calls from a panicked investor. And so on.

- Hard things have big rewards. Not financial, but emotional and spiritual. We’re hardwired to work. We’re hardwired to learn. In fact, for children, work, play and learning are all the same thing. We forget that as adults, but we never really changed. When work, play, learning, and challenge come together, we feel satisfied, proud, and energized.

- Don’t give up hard things at the end of a long day. Wait until morning. I nearly quit my bike trip after a particularly tough day of hills and heat. But the next morning, I felt a lot better. I was able to pedal a mile, and then that mile turned into two, and then I finished the whole day. Don’t make big life decisions when you’re tired. Do it when you’re fresh.

- Hard things become easier with a vision, or goal. Nobody has the stamina to brute force up all the wins that are required for success. One thing that makes the day to day grind possible is knowing that off in the distance, just over the horizon is the destination.

3. If it ain’t working, quit.

In the clear light of morning, rested, and with an eye towards the future, sometimes I find myself in a situation where my work is not aligned with my ideals, values, or goals. It doesn’t happen just once a lifetime, it happens frequently. Being intentional about the direction I’d like my life to go comes with an uncomfortable requirement that I frequently revisit the question: is my work getting me closer to my goals?

When the answer is no, I need to change something. I can adjust my activities towards making my job, relationships, or community closer to the thing that I want it to be. I can influence the organizations I’m a part of, working to making sure their actions support their stated ideals.

When my definition of success for GrubHub evolved from getting me out of debt to the more ambitious aspiration to help independent restaurants, it required massive change in activity. The company adopted the mission statement, “Make Delivery Better.” We reoriented around customer service and helping restaurants succeed. For me, personally, it was a golden age, surrounded by passionate, energized coworkers, making a profitable business, but also immensely helping our restaurant customers. After the 2008 housing crisis, a restaurateur actually brought me flowers, thanking me for keeping his business afloat during a deep recession.

“It takes Herculean effort to overcome inertia. And when it happens, we should celebrate the pursuit of intentionality.”

At times, reaching for success requires more significant change than working within my existing patterns. In that case, I needed to try something new entirely. Or, in other words, quit. There’s a narrative in the United States that equates quitting to giving up. We demonize quitting, attributing laziness, where none exists. But it takes guts to abandon a safe job. It takes courage to step into an uncertain future. It takes Herculean effort to overcome inertia. And when it happens, we should celebrate the pursuit of intentionality.

A dual commitment to working hard at the things we set out to do but also to quitting the activities that aren’t bringing us closer to our goals is INCREDIBLY FREEING. Knowing that we have the luxury of experimentation and giving ourselves the grace to fail allows us to take bigger risks and set bigger goals.

The biggest misperception I have faced about GrubHub is why I left. People insist I was tired, or I got rich, or had nothing further to contribute. None of these were true. The reality was that my definition of success requires that the communities I work in benefit from that work. I didn’t see any path to that happening anymore, and so I went my own way to start something new.

4. The finish line moves when you get close to crossing it.

As a person approaches the culmination of their difficult goals, they’re forever changed, and that new person finds themselves back at the start, once again urgently needing to establish a new vision. It’s the cyclical nature of the hero’s journey, of all human journeys. But, unlike a novel, it doesn’t finish at the end. It starts anew.

This has happened to me a bunch of times. It happened at GrubHub, as the company surpassed the point where I could pay off my student loans. It happened on my bike trip. I started the ride with an intention of discovering how to be present and how to unwind the stress of a decade of insane work. But by Kansas, that goal no longer resonated, and the bike trip became more about relationships with new friends.

It’s the joy and horror of success that as we approach it, we’ve grown, and therefore we don’t feel the desire to cross the same finish line. In some sense, we can’t ever cross that line, because we’re growing, dynamic people. But, and I’m hardly the first person to say this, it’s the journey, not the destination, so that’s OK.

5. Stop overthinking it and start already.

I created a multi-billion-dollar company from scratch and did a 4,500 mile bike ride. The facts are true, but that wasn’t my actual experience. I didn’t really do a 4,500-mile bike ride. I did ninety distinct fifty-mile bike rides. I didn’t sign up 70,000 restaurants to GrubHub. I signed up one. And then another, and then found people to help sign up more, and then found more people, and so on. The journey starts with the first step.

“The best training for week one is to just show up with a commitment to take it slow.”

But how do you do something so big? How do you get to the start line of a 4,500-mile bike trip? The best training for week two is week one. The best training for week one is to just show up with a commitment to take it slow. Keep at it, every day, and then sure enough, by Kansas, a 130-mile day will be no big deal.

Similarly, my advice for the aspiring entrepreneur is this:

If you see something that is broken, and it bothers you; if you can’t shake the feeling that it could be done better; if you look around and realize that nobody else is as annoyed by this thing, and that maybe nobody else is going to fix it, and that maybe, just maybe, you might be the person to do it—you can.

Don’t overthink it. Don’t write a business plan. Don’t hire a lawyer, or a market research firm. Just start.

Make the thing.

Sell a customer.

Start.

To listen to the audio version read by author Mike Evans, download the Next Big Idea App today: