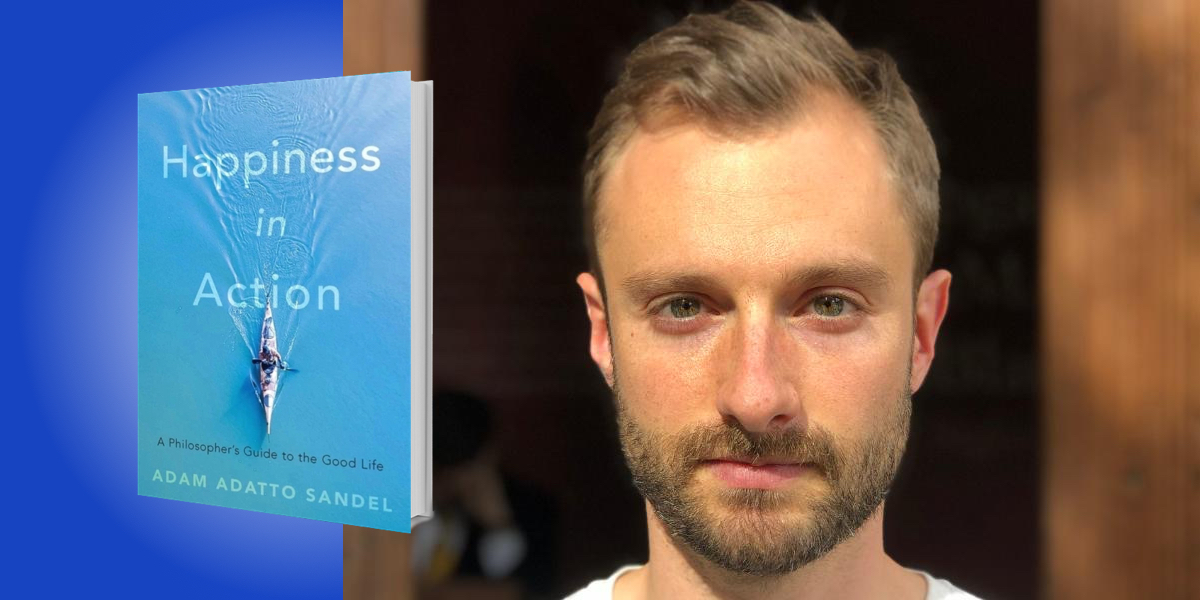

Adam Adatto Sandel is a philosopher and award-winning teacher who has taught at Harvard University. He is also an Assistant District Attorney in Brooklyn, New York, as well as the Guinness World Record holder for Most Pull-Ups in One Minute.

Below, Adam shares 5 key insights from his new book, Happiness in Action: A Philosopher’s Guide to the Good Life. Listen to the audio version—read by Adam himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Happiness is not a state of mind but a way of being.

We tend to think of happiness as a feeling or mental state—a sensation of pleasure or contentment. But this is the wrong way to conceive of happiness. To see why, we might consider an ancient Greek conception of the good life, what Aristotle calls eudaimonia. The word “eudaimonia” is typically translated as “happiness.” But it literally means “having a good demon by your side.” Eudaimonia suggests being on a path, living life in accordance with wisdom. It implies a mode of activity rather than a feeling or mental state.

What eudaimonia suggests is the connection of happiness to meaning and meaning to struggle. To be happy, in the deepest sense, is to be engaged in activity that speaks to a personal narrative, a story that coheres and gives one’s life direction, but that’s also unfinished and in the process of being clarified through encounters with the difficult and unexpected. The most meaningful activity, in this sense, may involve hardship and struggle. As we are engaged in it, we may be stressed or perturbed. And yet, paradoxically, we may be happy.

I’ve come to this insight not only from studying ancient philosophy but from reflecting upon the strange joy of being in the midst of a hard pull-up workout. At the end of a set of pull-ups, my arms are burning and my fingers start going numb with fatigue as I squeeze the bar. And yet, in that moment, I’m intensely engaged and full of life. As I attempt to rebound for one more rep, motivated by the shouts of encouragement from my training partner, and eager to test gravity one more time, part of me loves the struggle itself. When the set is over, the sense of satisfaction that accompanies it is inseparable from the process of struggle and overcoming.

This embrace of the activity itself, the struggle, is applicable to so many realms of life beyond the intensely physical. It could be writing a book, figuring out a problem, or simply attempting to understand a friend in conversation. The meaning of these activities and the joy they bring is inseparable from a process of resistance and overcoming.

2. The most meaningful activity is that which we do for its own sake.

This might be hard to accept at first. We’re used to thinking of meaningful activity in terms of aiming at goals that we imagine will bring us fulfillment: landing a dream job, reaching a personal milestone, getting married, having kids, devoting ourselves to making the world a better place. There’s nothing wrong, of course, with pursuing such goals. But goal-oriented activity, no matter how good the goal may be, is not enough for fulfillment. Even the achievement of our greatest goals brings only a fleeting satisfaction. We celebrate for an evening, bask in the afterglow of the achievement, but sooner or later, we find ourselves asking, “what now?”

“What we lose in goal-oriented striving is an appreciation for life in its unfolding.”

And yet, even knowing deep down that the goal-driven life leaves us stuck in a cycle of striving, achievement, and emptiness, we easily slide into defining our self-worth by how close we are to reaching our goals. The thought that “if I don’t land the job, get married, or reach the milestone, my life will in some respect be a failure” is a familiar way in which the goal-oriented perspective encroaches on our happiness. What we lose in goal-oriented striving is an appreciation for life in its unfolding. We lose a sense for life as a boundless journey in which unexpected encounters, challenges, and failures are integral to our character formation and self-discovery.

We also lose the sense of joy intrinsic to an activity that often enough led us to pursue it in the first place. Consider how a passion for artistic creation that finds expression with each stroke of the brush can turn into a harried effort to get a painting done on time for an upcoming exhibit. What we once enjoyed for its own sake as a distinctive form of passionate exertion becomes an object of success or failure. To find true happiness requires keeping in check our goal-driven striving and reorienting our lives to the intrinsic value of the activities that give our lives meaning.

3. Understand life as a field for the exercise of three virtues: self-possession, friendship, and engagement with nature.

On one level, these virtues are familiar to us. But in our frenzied effort to get stuff done, we lose touch with what these virtues really mean. Consider how we tend to equate self-possession with the spirit of “leaning in”—a kind of self-assertiveness in the workplace aimed at having an impact, winning supporters, and climbing the corporate ladder. We lose sight of the ways in which we might stand up for ourselves that have nothing to do with attainment, and that may even involve risking our goals for the sake of our dignity.

Similarly, we easily mistake friendship for alliance. An ally is someone who helps you achieve a goal. But a friend is someone who helps you put your goals in perspective. Consumed by the goal-driven life, we find ourselves with many allies, but few real friends. We overlook the kind of friendship that arises from a shared history and that enables us to grow in wisdom and self-understanding in each other’s company.

When it comes to engaging with nature, we face the immense difficulty of squaring our momentary appreciation of the “great outdoors” with all the ways we try to shield ourselves from nature and to exploit the earth for our purposes. We take pleasure in certain aspects of nature that fit easily with our daily routine, or that strike us as exotic novelties, and then turn our backs on the landscapes, forests, lakes, and oceans that we appropriate for industry. What we need to recover is an appreciation of nature as a source of wonder and awe from which we might gain new perspectives on ourselves and our humanity.

4. Self-possession and friendship are deeply connected.

Although we tend to think of self-possession and friendship as two separate virtues, one of which could be had without the other, they are actually deeply connected. When we recognize their connection, we gain a new appreciation for what each really means.

“As Socrates understood it, philosophy was not an isolated activity of abstract reflection but a mutually empowering form of discourse among lovers of wisdom.”

The reason we tend to view these two virtues as separate is that we assume an individualistic conception of the self. We assume that to gather one’s self and withstand external pressure does not necessarily involve the support of friends.

But we ought to reflect more deeply on how the activities that give our lives meaning, and that define our sense of self, imply a certain friendly relation to others. Here it’s worth considering, as an example, the life of the ancient Athenian philosopher Socrates.

In one sense, Socrates was the quintessential self-possessed individual. When he was accused by the city of Athens of corrupting the youth by encouraging them to question conventional authority, he boldly declared—in front of 500 Athenian jurors—that the unexamined life is not worth living. Ultimately, he even accepted the death penalty rather than renounce philosophy.

But Socrates understood himself not as a lone rebel but as someone motivated by a certain form of friendship. His very devotion to philosophy—which gave him the strength to defy the city—was a commitment to dialogue among those equally engaged in the pursuit of truth. The way Socrates practiced philosophy was by listening closely to the opinions of those with whom he conversed, attempting to enter their perspective and to derive some truth from what they said. As Socrates understood it, philosophy was not an isolated activity of abstract reflection but a mutually empowering form of discourse among lovers of wisdom. In this sense, philosophy was a powerful form of friendship.

So when Socrates stood up for himself against the city, he was really motivated by friendship as much as by his own sense of self. The example of Socrates leads us to consider the ways in which our greatest acts of self-possession attest to the support of friends.

5. At stake in overcoming the goal-driven life is finding a new relation to time.

We often think of time as a force that moves independent of us. We assume that whether we are aware of it or not, and regardless of what we do or think, time passes. But we ought to consider that the very meaning of time, and the sense in which it can be said to pass, depends on the stance we take toward our own being.

To the extent that we live in anxious preoccupation with achieving our goals, time always seems to fly by too fast. Immersed in the goal-driven life, we find ourselves plagued by the sense that there aren’t enough hours in the day. We also find ourselves plagued by the sense in which time slips away. The past, characterized by some former success or failure, rolls further into the distance as the future, in the form of some new aim or anticipated state of the world, barrels toward us.

Anxious that the future won’t turn out as we want, and haunted by past disappointments that still weigh on us, we live in constant dissatisfaction with the present. We treat the present as a waystation to a better future.

“It is only because past and future, closure and openness, coexist and constitute each other in every moment that life in the fullest sense is possible.”

But there is a way out of this anxious looking ahead and dejected looking back, a way in which we can truly live in the moment, and come to understand time as more than a sequence of moments that fly by. It requires learning to appreciate life as an ongoing journey—a journey that aims not at a goal, but at the ongoing commitment to being one’s self, standing by friends, and engaging with nature. In this way, the future and past take on a new meaning.

The past is the closure that orients life at every moment and gives it its meaning and sense. One could think of the past as the horizon of possibility from which dilemmas and choices present themselves as meaningful. The past is the way in which life already, in some sense, coheres. The future is the radical openness that encircles life at every moment and constitutes its mystery. The future is the ultimate beyond out of which the unexpected can break on the scene and put our lives to the test.

Understood like this, past and future aren’t separate. They coexist in a single moment, in every moment. Think about it this way: without the past, life would be utterly directionless, and would never be open to the future in the sense of the radically unknown. Without the future, life would be motionless, frozen over, and without inspiration or vivacity. It wouldn’t be life at all. It is only because past and future, closure and openness, coexist and constitute each other in every moment that life in the fullest sense is possible.

To the extent that we recognize this unity of past and future, take it to heart, and enact it in the way we live, we liberate ourselves from the fears of failure and loss that can make life so difficult to bear. In this way, we may seize upon a happiness that lasts.

To listen to the audio version read by author Adam Adatto Sandel, download the Next Big Idea App today: