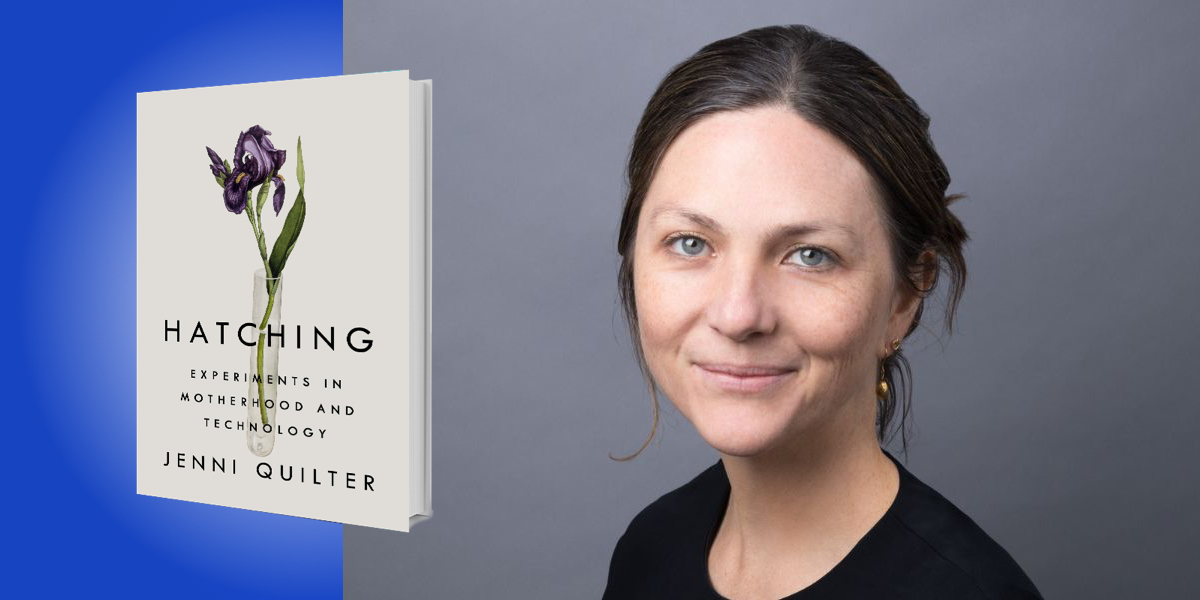

Jenni Quilter teaches at NYU, where she is the Executive Director of the Expository Writing Program and the Assistant Vice Dean for General Education at the College of Arts & Sciences.

Below, Jenni shares 5 key insights from her new book, Hatching: Experiments in Motherhood and Technology. Listen to the audio version—read by Jenni herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Baby-longing is culturally determined.

Most health organizations define a woman’s infertility as the inability to become pregnant after a year of unprotected sexual intercourse with a man, but that’s not always the case. When I was 35, I decided to freeze my eggs. I wasn’t in a relationship, and wanted to make sure it would be possible to have a baby later. I had always been ambivalent about having children—someday, but not right now. I had not fantasized about babies, had not grown up with them, and did not babysit them. In fact, up until that point I couldn’t even remember holding a single baby in my life. I had missed the boat, I thought, on craving motherhood.

But when I found out that I had far fewer eggs than a woman of my age should, I was devastated. I didn’t want to work, eat, or see friends. What had once been bulwarks in my world—solitude, work, exhilaration —hollowed out, dissolved, and I found myself caring very little about the future. Why, if I had been so ambivalent, had I stumbled upon such a vast plain of grief? Did I not know myself? I didn’t buy into the thought that this panic was “simply” my biological clock. My egg supply had probably been low for some time, and I hadn’t even known.

Some people would call this a biological or hormonal urge, or evolutionarily natural. I remain unconvinced that we should rationalize it this way. As Population Researcher Anna Rotkirch has pointed out, “most parents in human history have had their children before they had the time or opportunity to long for them.” When baby longing appears, it tends to be tied to the culturally expected age of birth, rather than any biological demarcation of fertility. It comes when a person senses that in a parallel life, they could have been a parent by now: the opportunity has presented itself, and they have not pursued it. They are grieving a decision they did not make. The age at which this longing appears is culturally subjective and gendered. In Tanzania, the average age for first births is nineteen, in India, sixteen. In the United States, it is twenty-seven.

“Without realizing it, I had considered motherhood as a kind of automatic meaning making machine.”

I had underestimated the structural logic of motherhood. When I was in my twenties, I read about image schemas, which were a fancy way of naming recurring structures in our cognitive processes which establish patterns of understanding and reasoning. According to this theory, our bodily experiences as babies direct our later linguistic experiences and expressions: our most basic spatial patterns (in/out, up/down, etc.) structure figurative language and abstract reasoning. For example, we might metaphorically project the spatial direction “out” without thinking twice into more-conceptual sentences like “Tell me your story again, and don’t leave out any details,” or “She finally came out of her depression.”

At the time, this knowledge helped me see how insidious sense-making was in poetry; even if a poet strains to be dissociative, their brain couldn’t help but use coherent image schemas. In contemporary poetry that appeared to describe impossible scenes, basic sense lurked in the lines, spatial views appearing like the outlines of old shipwrecks buried under sand. Image schemas function as a secret cognitive and linguistic glue, holding us together even when we try to linguistically fall apart.

Motherhood felt like that to me. I knew, consciously, that my own baby desire was far slighter than that of the other women I knew. I had also unconsciously accepted that giving birth would act as a fulcrum, a kind of tipping point. This was not so much about wanting a baby as expecting a life shaped by one. What would my life look like without that central event around which everything else gained interpretive symmetry? No wonder I was bereft. Without realizing it, I had considered motherhood as a kind of automatic meaning making machine. Now I was exhausted by the prospect that I would have to craft this meaning on terms that would not be immediately or easily understood by people around me.

2. Modern technology has revolutionized how we see pregnancy and the beginning of life.

The ability to look inside our bodies has radically changed our understanding of our reproductive choices. To see your insides with your own eyes—rather than simply to possess them unconsciously and involuntarily—is a remarkably recent development. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, you could not look inside yourself while you were alive. Ultrasound technology, first developed in the 1950s by a British surgeon named Ian Donald, was one of the first comparatively “harmless” ways of looking inside (as opposed to the radiation caused by X-rays). Ultrasound has become so ubiquitous that people now announce a pregnancy with an ultrasound photo: no one thinks twice about the verification of life as image.

In the 1960s—right as the pill was legalized, and at the height of the post-World War II baby boom—a number of books and magazines detailed color photographs of fetuses. The most famous were Lennart Nilsson’s photographs for Life magazine in 1965. You’ve probably seen these photos without knowing who took them. You can trace the developing capillaries in the fetus’s legs, as distinct as the veins on a tree leaf, the caul like tissue paper, the fine hairs on the forehead. In other words, at precisely the time when women sought more choice, their sense of what that choice amounted to was also changing.

Through this kind of photography and ultrasound, we have now learned to humanize fetuses in a way that would have been deeply unfamiliar to women who could not look inside themselves even 200 years ago. Saint Augustine argued that “ensoulment” happened when a woman experienced “quickening,’ which was her sensation of the fetus inside (usually at four to five months). This was the official position of the Catholic Church until the nineteenth century (though there were a few early Christian writers who argued that early abortion was infanticide). Other theories mark the arrival of the soul as being at the time of birth, or the time the child first laughs. But by now, it is difficult for any woman born into the late twentieth or early twenty-first century to not think of fetal photographs and ultrasounds when she thinks of life inside her.

3. IFV does not have to be expensive.

Most people understand in-vitro fertilization to be a privilege for the wealthy, the well-insured, or those living in a country with a generous social safety net, but IVF has been proven to work at a fraction of the cost.

For the past 15 years, Willem Ombelet, originally from South Africa and long based in Belgium, has led the charge to lower the cost of IVF in Africa. In 2008, he happened to ask a colleague about hand-me-down IVF equipment. That colleague, Jonathan van Blerkom was, initially skeptical; it’s not just the equipment you need, but the personnel and infrastructure.

Months later, driving home, he recalled how, as a graduate student, he drove rabbit and pig embryos from Arizona to Colorado, keeping the embryos alive in a very simple combination of sodium bicarbonate, water, and citric acid. It was relatively easy to monitor the pH balance; if it got too high, he just needed to inject some CO2. You could, he reasoned, do the same with human embryos. He also thought of how you might generate that CO2. As a child, one of his favorite toys was a plastic scuba diver he’d purchased with box tops from Kellogg’s corn flakes. One chamber of the tank was filled with vinegar and the other with baking soda. As the contents reacted with each other, they gave off CO2, causing the diver to dip and resurface, releasing bubbles. Van Blerkom wondered if you could keep an embryo alive using the same technique.

“Using conventional IVF resulted in a 29 percent live birth rate. Using this new method, the rate was 30.4 percent.”

The result of Van Blerkom’s thinking was an embryology kit that fits inside a shoebox. It looks a lot like a high school science experiment, with its modest metal casing, glass tubing, and basic cork stoppers. The materials barely cost more than $10. In a conventional IVF clinic, approximately 35 percent of running costs are spent in the laboratory. Some of this is diagnostic blood and semen work, but then there are also the considerable operating costs of an embryo lab, which include staffing, equipment, and maintenance. Incubators are extremely costly, as are air purifiers and ventilation hoods.

Ombelet and Van Blerkom rethought a few basic assumptions; What would happen if you reduced the number of times an embryo was moved from one receptacle to another, or removed from the incubator for observation? You wouldn’t need quite the same emphasis on air quality control, and you wouldn’t need as many trained embryologists. They reasoned that it was quite possible to combine sperm and egg in the test tube and leave the ensuing embryo to grow, rather than removing excess sperm. They also thought it quite possible to find a microscope that would work well enough through glass. If this was true, then the only remaining requirement was a consistent temperature, and this was relatively easy to achieve with a minimum of equipment.

They then had to establish whether such a low-cost method would work as well as conventional IVF. Ombelet designed a study to submit to the Belgian Ethics Committee wherein a number of couples younger than 36, with a sperm count of more than 1 million, received ovarian stimulation. If the oocytes harvested numbered more than eight, half were fertilized and cultured the usual way, and the other half using the new method. An independent embryologist, blinded as to which were which, would then select the best embryos to implant, and the others would be frozen.

The results were remarkable. Using conventional IVF resulted in a 29 percent live birth rate. Using this new method, the rate was 30.4 percent. Sixteen live births resulted from embryos that had been cultured using the low-cost method. The implications for the developing world were clear. If you could find a clinician to prescribe a hormone stimulation protocol, who was also able to carry out laparoscopic surgery, you could possibly conduct IVF anywhere. At the very least, IVF could cost less than 920 euros in a country like Belgium, which was little more than $1,100 U.S. dollars. Right now, the cost per cycle in the United States is between nine and twelve thousand dollars.

4. Science with a grain of salt.

One of the first things you are often given at an IVF clinic is a series of laminated charts of their implantation rates, essentially their sense of your odds with them. If you’re a 35-year-old woman with no underlying other complications, chances of a successful embryo implantation is 30 percent, chances of a full-term pregnancy are 25 percent, and so on.

When you’re given these charts, it is very easy to become very numbers-focused. You develop your own number sequence: your blood hormone levels, the numbers of oocytes in your ovaries, the number of retrieved eggs, etc. You can see this focus on numbers in a lot of the online message boards, where patients gather to commiserate, celebrate, and strategize. These numbers also generate an awful amount of pressure, and when your numbers are not what they should be, it’s easy to feel despondent. Having gone through it all, the thing I wish I had known at the beginning was that all numbers need to be taken with a grain of salt.

“To assume that one’s infertility is a fixed, static condition is a little like assuming that because everyone else on the freeway is driving faster than you, you’re not going anywhere.”

My numbers were terrible. Terrible. I wish I had known then that all kinds of outcomes are possible, and that acknowledging this possibility wasn’t an exercise in magical thinking or religious faith, but the realization that there are ever-evolving limits to science. The field of reproductive technology is constantly shifting, including the ways in which clinics value or weigh various indicators of infertility or hormonal stimulation. There are still some things about the human body we still don’t really understand. (This is true of every human endeavor, and I’m amazed how quickly we forget it when we’re told we’re “dealing with experts.”)

The field of reproductive technologies is wonderfully dynamic in that sense. To assume that one’s infertility is a fixed, static condition is a little like assuming that because everyone else on the freeway is driving faster than you, you’re not going anywhere. Your body is always doing something, and the horror and the marvel is that sometimes you don’t know what that is. Conceiving is a maddeningly complex thing, which is why it’s important to take the simplicity of those laminated charts with a grain of salt.

5. Motherhood is an experiment.

This is not meant in a provisional or lighthearted sense. You don’t experiment with motherhood the way you do with bangs or jeggings. “Experiment” is meant in a scientific sense; in the sense that there is a method, a sense of real risk, a genuine sense of not-knowing and then finding out. There is something to be discovered by becoming a mother, rather than something that is only confirmed.

I first really understood this when I read Naomi Mitchison’s novel Memoirs of a Spacewoman. It was published in 1962 and I picked it up around 2017. The book collects the “expedition notes” of a spacewoman called Mary and her visits to various planets. It is the ventriloquized voice of the future, a way for Mitchison to imagine the fantasies and freedoms she thought the future might afford a woman like her.

In the novel, Mary has six children. Four of the children are human, and two are aliens. One child, Ariel, is a tentacle-like creature with whom Mary communicates through number theory (the tentacle can tap out number sequences on her leg). Another, Viola, is described as half-human, half-Martian. Mary conceives a few of these children back on Earth, and a few in space. Some, but not all, have biological fathers. Mary does not raise all of them together. In this new world, her age has nothing to do with her reproductive clock. Because time moves more slowly away from Earth, and because she embarks on a number of space missions to different worlds and solar systems, each time Mary returns to Earth she returns to a different world: there is no one who ages contiguously with her, no lover, no family, not even her own children, who are infants when she embarks on one trip, then teenagers when she returns—and she has only aged one year.

For anyone who has felt the queasiness of pregnancy, the sudden conviction that your body is not your own, the inner roiling and the splitting open, the endless days and nights of cleaning and feeding, Mitchison’s freedoms are fascinating. For anyone who has not fallen pregnant or raised a child, but who has been caught between the fearing and the yearning, Mitchison’s recasting of the obligations of parenthood is also irresistible. Mary has a biologist’s eye in her attention to cause and effect, and is obviously interested in how our physiological structure directs our cognitive and moral frameworks. Her tone is professional, even impassive: she sees no disconnect between scientific exploration and reproduction, and is not surprised that her expeditions involve physiological experiments of more than one kind. Her pregnancies defamiliarize two discourses—one of scientific knowledge, the other of motherhood—at the same time. In her book, I saw for the first time what motherhood, conducted as a pursuit of knowledge, might look like.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jenni Quilter, download the Next Big Idea App today: