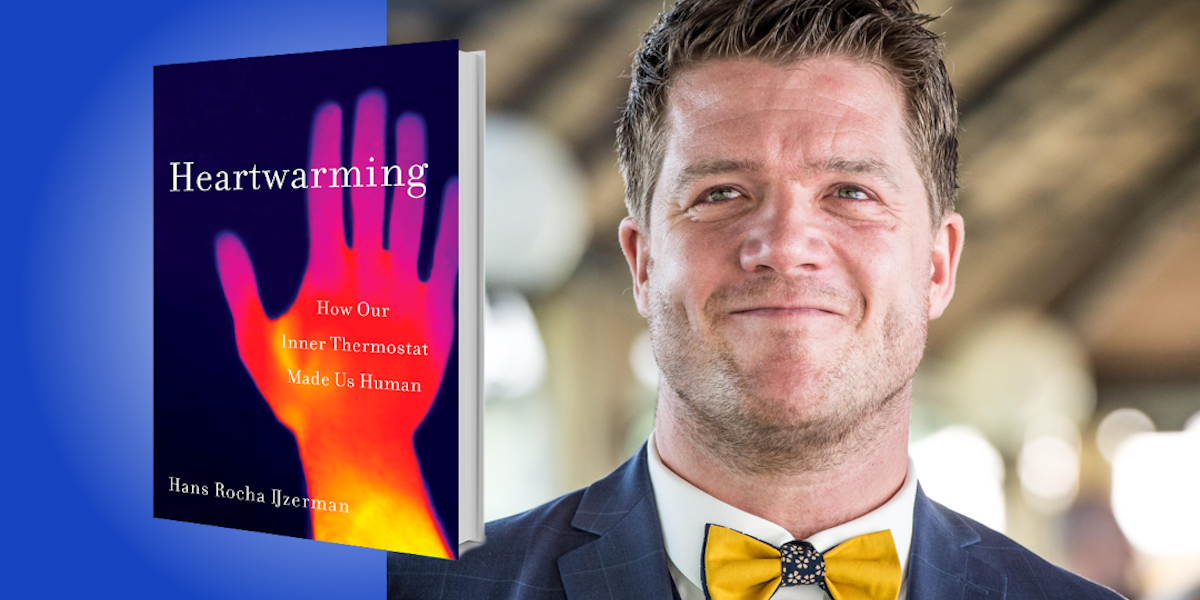

Hans Rocha IJzerman is an associate professor in social psychology at the Université Grenoble Alpes and the foremost expert on social thermoregulation in humans. His writing has appeared in the New York Times and the Huffington Post.

Below, Hans shares 5 key insights from his new book, Heartwarming: How Our Inner Thermostat Made Us Human. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. The hidden importance of temperature.

In modern life, we have all kinds of ways to regulate our temperature almost immediately—we wear certain clothes, or we turn on the air conditioner, for example. For most of human history, however, this near-constant regulation of temperature was impossible, even though temperature changes all the time. And if you don’t regulate temperature successfully, you die. This is why temperature affects almost every domain of our lives, from the way our body is shaped (animals like us with long limbs fare better in warmer climates) to how we speak.

In fact, different languages have different terms for temperature. Some languages distinguish between cold, lukewarm, and warm, while others only have two temperature terms like “cold” and “warm.” Languages also differ in whether they metaphorically combine warmth and affection—in English, you can say that someone is “giving you the cold shoulder,” for instance. Out of 84 languages I describe in the book, 52 of them use such heat-based metaphors.

2. Other people are like an investment portfolio.

The fact the temperature changes all the time means that we need a variety of mechanisms to cope with it. When temperatures go up, we usually down-regulate temperature by ourselves—either internally by sweating, or via behavioral thermoregulation by staying in the shade or jumping in a pool. But when temperatures drop, we have a bit more time to respond, and that opens up possibilities.

“We need to build up strong, intimate bonds with people who can protect us from the environment when it takes its toll.”

We can heat up our bodies ourselves by shivering, but that’s not the most metabolically efficient way to do it. Instead, we may outsource temperature regulation to others; a variety of species huddle together as a cost-saving mechanism, from penguins to the African four-striped grass mouse to the antelope ground squirrel. Huddling reduces the metabolic cost of the cold, and humans similarly rely on others for cost-saving purposes. So in a way, it makes us quite rational to invest in other people. We need to build up strong, intimate bonds with people who can protect us from the environment when it takes its toll.

3. The protective role of gezelligheid.

In our research, when we experimentally manipulate a temperature to be lower, participants tend to think more about people they feel close to, and they have a greater desire to be in touch with people. This effect occurs primarily for those with positive experiences in relationships, people who feel comfortable investing in the relationship portfolio.

This phenomenon reminds me of a concept from my home country, the Netherlands, which is known as gezelligheid. It’s the warm atmosphere and coziness that you feel when sitting around a fire with other people during a cold winter. Perhaps one of the most remarkable effects that represents gezelligheid is one that we detected with exploratory data analysis. In a sample of over 1,500 people in 12 countries, we found that one of the best predictors of people’s core body temperature was the diversity of their social network. The more types of social groups they participated in—like being in a volunteer group, a sports team, or a group at work—the better protected their core body temperatures were if they lived in a colder climate.

“One of the best predictors of people’s core body temperature was the diversity of their social network.”

4. The surprisingly sneaky act of kleptothermy.

Kleptothermy is the act of stealing temperature. Male garter snakes in Canada, for instance, pretend to be female by producing feminine pheromones, so that other males will try to mate with them. As many as 100 snakes can climb on top of one such deceitful male, warming his body under false pretenses. Amphibious sea snakes of New Caledonia also engage in heat theft by sneaking into boroughs occupied by large tropical seabirds, taking advantage of the body heat that warms the space. In a similar fashion, lizards, snakes, and dwarf caimans freeload on the heat produced by termite mounds. Schneider’s dwarf caimans, for example, place their eggs beside or on top of termite mounds to ensure that they stay warm.

5. Don’t oversimplify how human behavior works.

My field, psychology, is often guilty of oversimplifying human behavior. One famous applied methodologist keeps insisting to me that physical warmth should simply make people feel good, for example. But warmth doesn’t exclusively produce good feelings—it depends on the context. During a hot summer in Grenoble, France’s warmest city, I often long for a cold beer. Furthermore, there’s not even strong evidence for the idea that going through a cold winter leads to seasonally related depression, something many people thought to be a near certitude. So making simple, straightforward connections like this does not reflect how human behavior works. We need epistemic humility. But with improved measurement capabilities and more diverse samples to work with, I believe that over time, we will get closer to the truth.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: