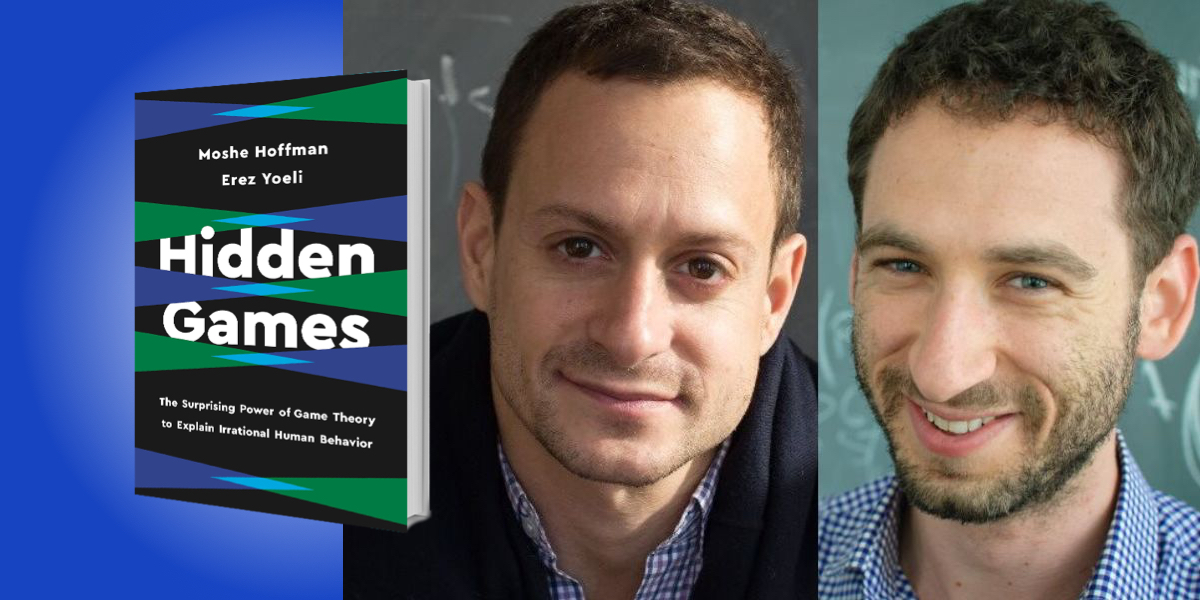

Moshe Hoffman is a research scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology and a research fellow at MIT’s Sloan School of Management. Erez Yoeli is a research scientist at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, the director of MIT’s Applied Cooperation Team. They both lecture in Harvard’s department of economics.

Below, Moshe and Erez share 5 key insights from their new book, Hidden Games: The Surprising Power of Game Theory to Explain Irrational Human Behavior. Listen to the audio version—read by Moshe and Erez themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. People are weird.

Just take our sense of aesthetics. In some places in the world, it’s common for men to grow long fingernails, especially long pinky nails. Now, to most of us, men with long fingernails aren’t so attractive, yet when we asked the men why they grow long fingernails, they said it was because they find them beautiful.

Here’s another example of our strange sense of aesthetics: The complex rhyme schemes of rapper MF Doom. His intricate verses pose two puzzles. First, there’s something kind of funny about the fact that an entire art form grows up around an artificial constraint like rhyming that, in fact, makes it pretty hard to communicate. Think about how much harder it would be to tell a family member or a friend how your day went if you had to rhyme almost every word with another word. Second, MF Doom’s rhymes are so subtle that the average listener is likely to miss them. This begs the question: Why is art so often subtle, and prized for that subtlety?

Another thing that makes people weird is our sense of altruism. You might know that Americans are very generous, donating roughly 3 percent of GDP to charity each year. That’s as much as we devote to R&D. Yet when we give, we tend to do it in odd ways. In surveys, most people admit that they don’t even check how good a charity is before giving to it. So why do we give—and why do we give so ineffectively?

2. Don’t give proximate explanations.

Proximate explanations are explanations that rely on what we think or feel. If you ask an MF Doom fan why they like the rapper’s complex rhyming schemes, the fan will probably tell you, “I like that beat,” or “I like how that sounded,” or “I like the way that rhyme flowed over the bar.” That doesn’t explain why they like those beats or rhyming schemes.

If you ask a volunteer at a charity why they wanted to support that particular organization, they may tell you, “It helps me feel connected” or “It helps to build a global community.” But again, that doesn’t explain why it makes them feel connected, or why they care so much about building a global community.

“To understand why people are so weird, we have to go beyond the proximate—and game theory helps us do just that.”

To understand why people are so weird, we have to go beyond the proximate—and game theory helps us do just that.

3. Game theory is a powerful tool.

At its core, a game just has three parts. There are players who choose from some actions and they get payoffs. It really is that simple. To make this game theory, though, we have to add two more things. First, those payoffs are going to depend not just on the player’s choice, but also on what others are doing. Second, there needs to be some sense that the players make their choice optimally. That’s it. That’s game theory in a nutshell.

Traditionally, game theory has been used to try to understand the behavior of companies (like, say, when they’re merging, what might happen to prices), the behavior of bidders in an auction (how changing the rules might change their bids and the amount of revenue that the auctioneer receives), or for statecraft (a famous application of game theory is to nuclear brinkmanship).

Game theory can help us make sense of some counterintuitive stuff. For instance, you might have heard of the Dutch tulip mania of the 1600s. During this time, a single tulip bulb could cost as much as hundreds of pounds of cheese. Yet in some auctions, if nobody bid high enough for the bulb, then the auctioneer would just crush it. That’s nuts! Why not simply let the price drop further, or try selling it again later? Game theory teaches us that at least in certain circumstances, destroying the bulb can increase the expected revenue from the auction.

Game theory often yields weird results like this, which is what gives it its power to explain all sorts of otherwise puzzling behaviors. That’s what makes game theory so powerful.

4. Game theory doesn’t require rationality.

You may have read books like Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene, which use game theory to explain a variety of puzzling animal behaviors and traits. Game theory has been used to address why in some species the ratio between males and females at birth is 50–50. Then there’s the hawk-dove model, which people use to talk about animal territoriality. Or consider the costly signaling model to talk about peacock’s tails—why would any creature evolve such an absurd tail? That was a question that Darwin said made him feel sick because he couldn’t understand it.

“Another way we optimize is cultural evolution—the idea that our tastes and beliefs are shaped by learning through experience or socially from others.”

Of course, these kinds of answers have nothing to do with rationality. All we need is for there to be some kind of optimization going on. And in these cases, biological evolution is doing that optimization.

Another way we optimize is cultural evolution—the idea that our tastes and beliefs are shaped by learning through experience or socially from others. This kind of argument has been used to explain why people in some cultures develop a taste for spicy foods, or why Native Americans develop a taste for corn that’s cooked with a bit of ash or lime, or why people start to believe in certain food taboos that keep them from ingesting dangerous toxins during pregnancy.

Game theory doesn’t require rationality, just some optimization process.

5. The game is often hidden.

Remember those men who grow long fingernails because they think long nails are beautiful? When we dug a bit deeper, we found that those with the long fingernails were secretaries, teachers, and mayors—people with indoor jobs. These were jobs that would both allow you to grow your nails long, but also carried a bit more prestige within the community. So one explanation here for the long fingernails is that they signal something about people’s occupation. But that game was hidden.

What is the hidden game when it comes to altruism? Here, the game might have more to do with reputations. We’re not saying Habitat for Humanity volunteers sign up just so they can put some photos up on Instagram. They genuinely want to do the right thing and genuinely feel good swinging those hammers. But below the surface, there’s a hidden game going on that helps to shape those righteous beliefs and good feelings. And this hidden game, if we take the time to understand it, can help us understand why folks who want to do the right thing are the same folks who do it in such ineffective ways.

To listen to the audio version read by co-authors Moshe Hoffman and Erez Yoeli, download the Next Big Idea App today: