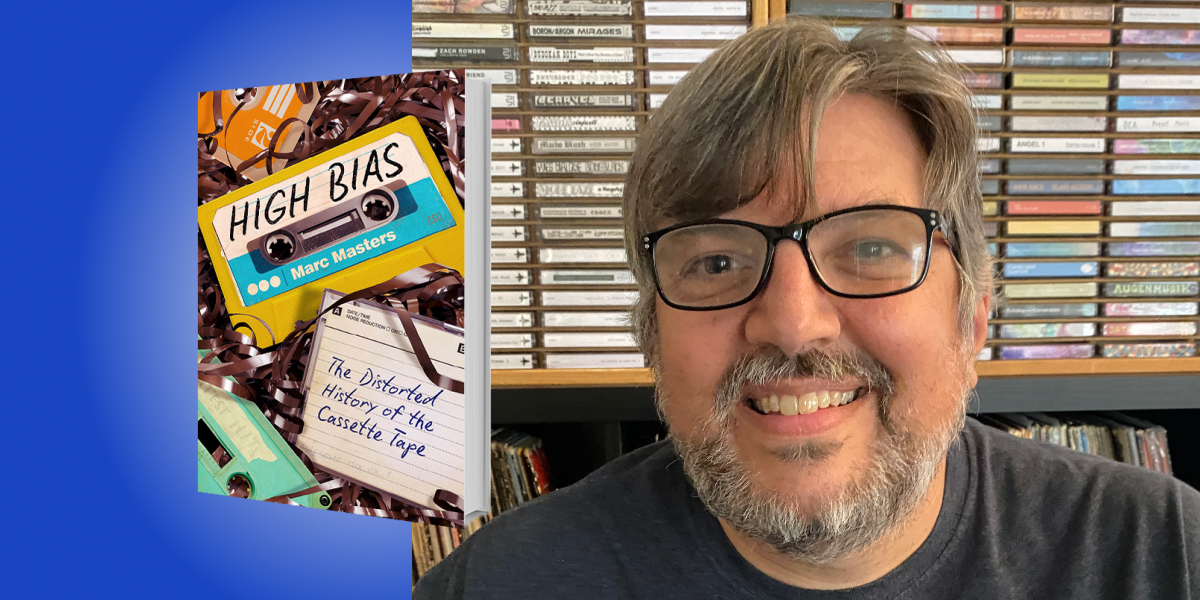

Marc Masters is a music writer for publications like Pitchfork, NPR, The Wire, the Washington Post, Rolling Stone, and Bandcamp Daily.

Below, Marc shares five key insights from his new book, High Bias: The Distorted History of the Cassette Tape. Listen to the audio version—read by Marc himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The cassette tape was a radical invention.

When the cassette tape came along in the early 1960s, magnetic tape as a recording medium had existed for a while, most famously as reel-to-reel tape. But this new version, originally called the “compact cassette” by Lou Ottens, who created it when working at Dutch company Phillips, was the first that truly was compact.

Ottens wanted it to be small enough to carry in your pocket, easy enough for novices to operate, and cheap enough that a non-professional could afford it. Just as importantly, Ottens and Phillips decided to make their design free to other companies, so the compact cassette circulated fast and quickly, becoming the standard product we now call the cassette tape. Suddenly almost anyone could easily record music, something no format had offered before, and something that threatened the music industry, who went so far as to start an ad campaign whose motto was “Home Taping Is Killing Music.” But music survived—and so did the cassette tape.

2. The cassette tape made music personal.

Ottens thought his compact cassette would be primarily used for voice recording because he wasn’t sure the audio quality was good enough for music. But many musicians and fans didn’t care about that; they just wanted to be able to do things themselves, so they quickly started copying and sharing music on cassettes.

“We take for granted now that music fandom is an expression of identity.”

Trading tapes became an act of friendship, forging personal relationships over music. In addition, carrying music around everywhere became a new way to personalize your relationship with music, something that became especially common after Sony introduced the Walkman. Suddenly, something you only did at home could be part of every part of your life, and it seemed like everyone walking down the street was now soundtracking their own lives, using something that was almost like a new appendage on your body. We take for granted now that music fandom is an expression of identity, but without the cassette tape, it never would have become so personal.

3. The cassette tape helped create music.

Whole genres of music grew up around the cassette tape. The most important example is hip-hop, which started as the music at live DJ parties in New York. DJs such as Kool Herc and Grandmaster Flash pioneered new ways of mixing and cutting records into what they called “breakbeats.” There were so many of these parties that no one could hear them all—unless they managed to find a tape that someone had made and passed around.

Eventually DJs themselves made cassettes of their own sets and sold them after shows or on the street, circulating their new sounds, which in turn influenced other DJs. Styles mutated and evolved like wildfire, long before hip-hop made it onto official releases on professional industry labels. These so-called mixtapes were so crucial that even today when hip-hop artists share their work digitally, it’s often still called a mixtape. The same kind of thing happened with heavy metal, go-go, indie rock, New Age, and many other genres percolating outside the realm of music industry gatekeepers because everyone involved was dubbing their music and sharing it with each other.

4. The cassette tape is an archive of musical history.

In many non-Western countries such as India, Syria, and Iraq, forms of folk music played by local musicians in homes and on the streets were shunned by the music industry and by state-run radio. This was especially true in Egypt, where a working-class genre called “shaabi,” meaning “of the people,” was banished from the airwaves, accused of being too “vulgar” for the masses.

“The folk sounds of towns, counties, and countries are a vital part of history.”

Music like this basically vanished in the air after it was performed—until the cassette tape came along. People began taping music performed in storefronts, at parties and weddings, and eventually started dubbing those tapes and selling them at kiosks and corner stands. The government of Egypt even set up an Office of Art Censorship to monitor all these releases, but there were so many coming so fast that they couldn’t keep up.

Now, many years later, much of that music only survives on cassette tape, and collectors scour dusty bins trying to rescue these artifacts of past musical forms. The folk sounds of towns, counties, and countries are a vital part of history, and if the cassette tape hadn’t been there to document, it surely would have been lost.

5. The cassette tape isn’t dead.

Ever since CDs overtook tapes in sales in the 1990s, people have pontificated about the death of the cassette format, framing it as, at most, a symbol of nostalgia or perhaps kitsch rather than a useful format. But these elegies have always been premature because the cassette tape never actually went away. People continued to use it for what was unique about it: cheapness, simplicity, and portability.

In recent years, the cassette tape has enjoyed a kind of resurgence, particularly among small independent labels. These labels can’t afford the high prices and long wait times associated with pressing vinyl records, and their fans are turned off by the impersonal nature of streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music. They prefer to buy something tangible directly from artists rather than listening to their music in a way that barely pays them pennies. In turn, some big labels have recently begun to sell releases by blockbuster artists on cassette. That aspect of the tape resurgence might just be a passing fad, but for those who still value the things that originally made the cassette tape such a unique and useful format, it’s never going away.

To listen to the audio version read by author Marc Masters, download the Next Big Idea App today: