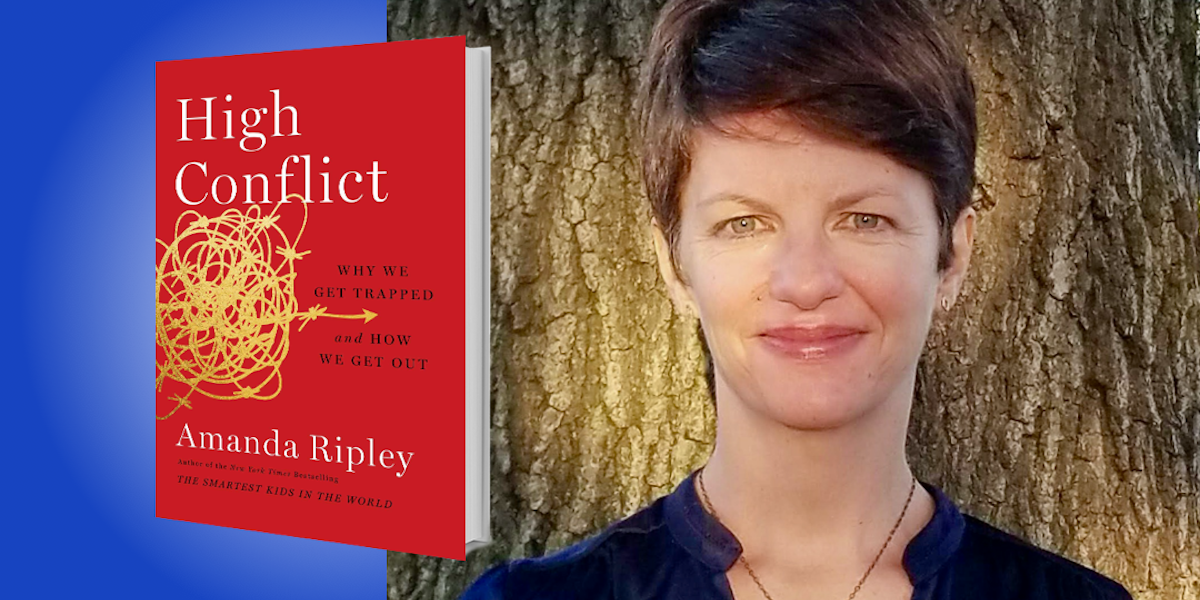

Amanda Ripley is an investigative journalist and the New York Times bestselling author of The Smartest Kids in the World and The Unthinkable. She writes for The Atlantic, Politico, the Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal, among other publications.

Below, Amanda shares 5 key insights from her new book, High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out (available now from Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to listen to the audio version—read by Amanda herself—and enjoy Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. You can’t avoid conflict.

These days, we see a lot of high conflict—the kind of conflict that takes on a life of its own, the kind that starts small but quickly becomes all-consuming. As the original facts that led to the dispute fade into the background, replaced by an us-versus-them dynamic, the conflict becomes its own reality. High conflict is invisible, but like gravity, it exerts a pull on everything else—and anything you do to try to end high conflict usually makes it worse.

But there’s no need to lose hope—you don’t have to give up or change your mind or stop fighting for what’s right. You just have to turn high conflict into good conflict. That’s the kind of conflict that can be heated and stressful, but actually goes somewhere worth going. It’s a way of fighting smart. Decades of research have shown that the problem with conflict is not the friction; the problem is high conflict, the kind that paralyzes us, blinds us to opportunities, and eventually makes us act against the causes we care most about.

2. Humiliation is the nuclear bomb of the emotions.

Why do some conflicts stay manageable while others implode? It turns out humiliation plays an outsized role. Humiliation is the most powerful, under-appreciated force in any conflict you can think of—politics, international relations, gang violence, even homeowner association disputes. It’s “the nuclear bomb of the emotions,” as the psychologist Evelin Lindner puts it. Researchers have found that feelings of rejection and humiliation activate the same parts of the brain as physical pain, which is why it’s often called “social pain.” And social pain usually causes people to become aggressive in response, which fuels high conflict.

“Usually, the understory has something to do with fear, humiliation, and a need to belong.”

3. Beware the binary.

Democrats and Republicans, white and black, good and evil, us and them—these binaries rarely reflect reality, yet they’re potent enough to bring out our worst conflict instincts. In order to break out of binary thinking, it helps to purposefully mix up categories. If you want to stay out of high conflict in your school, company, or country, create more than two groups. And keep them fluid—scramble them up every so often. Want to open a branch office? Rotate your employees in and out on a regular basis. Want to be a great school principal? Teach a class yourself, just like the teachers. Take a class, too, just like the students. Don’t let groups stagnate and take on outsized importance.

4. Investigate the understory.

Every high conflict has an understory—the thing it’s really about—which almost never gets discussed. Usually, the understory has something to do with fear, humiliation, and a need to belong. And until that understory gets investigated, high conflict rages on, like an uncontrolled wildfire. To get out of high conflict, you have to investigate the understory by asking, “What is the root cause?”

That is the question Curtis Toler, a former gang leader, asks young men on the streets of Chicago. Often, the people in high conflict don’t really know the answer since no one has asked. So help them get curious about it—what does QAnon mean to its followers? What does the COVID vaccine represent to its skeptics? Taking the time to excavate root causes is one of the best ways to turn high conflict into good conflict.

“Whenever an opportunity arises, we can help people realize they have reached a saturation point, and invite them to come home.”

5. Watch out for saturation points.

The great weakness of high conflict is that it makes everyone involved kind of miserable. They want it to stop, but they can’t figure out how. This misery creates saturation points, moments in a conflict where the losses outweigh the gains—but a saturation point can be a golden opportunity to interrupt conflict. A couple in a bitter custody battle, for example, might reach a saturation point if their child gets sick. Suddenly, their priorities realign. With gang members, it might happen in the hospital after someone’s been shot. In politics, it can happen after a loss.

This happens in war, too. In Colombia’s long-running civil war, 52,000 people left the armed conflict voluntarily through the government’s reintegration programs. What caused them to leave when they did? They reached their saturation points. Sometimes it was when their side experienced major casualties or ran low on money and food. It also happened, according to fascinating research by Juan Pablo Aparicio, when the government ran ads during big sporting events, inviting the rebel fighters to come home and watch the game with their families.

In other words, people on the outside of a high conflict matter—those of us who are not calling each other names on Facebook, who are not “conflict entrepreneurs.” Whenever an opportunity arises, we can help people realize they have reached a saturation point, and invite them to come home.

To listen to the audio version read by Amanda Ripley, and browse through hundreds of other Book Bites from leading writers and thinkers, download the Next Big Idea App today: