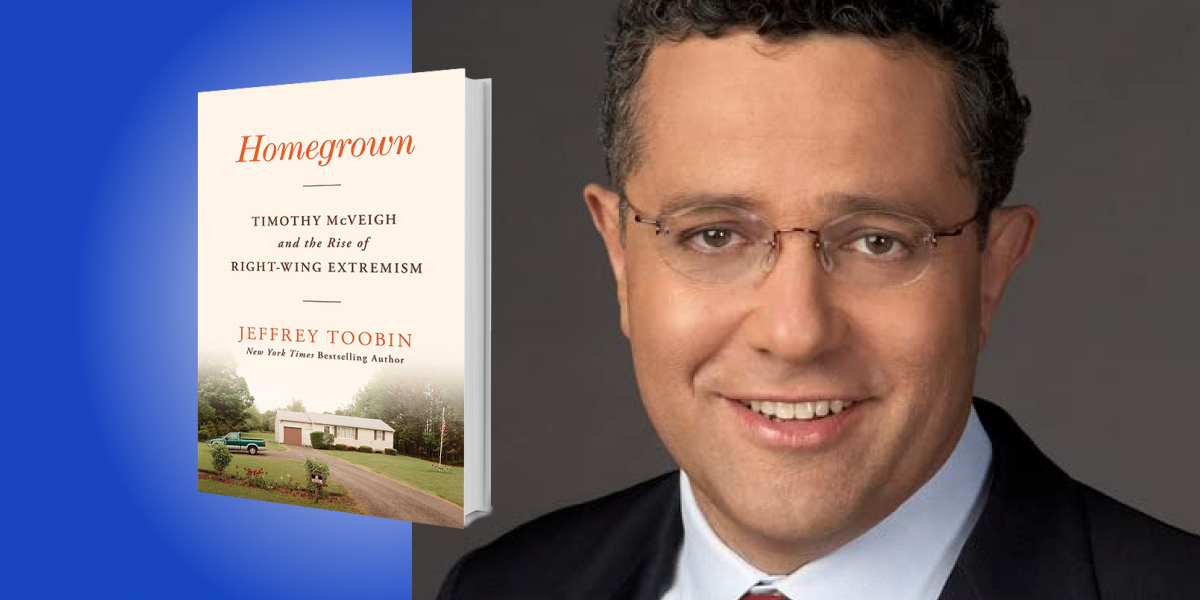

Jeffrey Toobin is a New York Times bestselling author and magna cum laude graduate of Harvard Law School. His bestselling books include American Heiress, The Oath, The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, Too Close to Call, A Vast Conspiracy, The Run of His Life: The People vs. O.J. Simpson, and Opening Arguments.

Below, Jeffrey shares five key insights from his new book, Homegrown: Timothy McVeigh and the Rise of Right-Wing Extremism. Listen to the audio version—read by Jeffrey himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Timothy McVeigh was not simply a lone wolf eccentric.

Most people know something about the Oklahoma City bombing. They know that it was April 19th, 1995; they know that 168 people died, including 19 children; they probably know that Timothy McVeigh set off the bomb. But what makes this story so important today, 28 years later, is that McVeigh was not, as he is often described, some sort of lone-wolf, anti-government eccentric.

Timothy McVeigh was a right-wing extremist. He was part of a political movement in the 1990s. He was a dedicated listener to Rush Limbaugh. He believed that Vince Foster, the White House aide, who committed suicide, was murdered by the Clintons. When he did target practice in the fields of Kansas, he used a photograph of Hillary Clinton’s face on top of the silhouettes he was shooting at.

He was part of a right-wing extreme movement that has continued to this day. If you look at the obsessions of the people who attacked the Capitol on January 6th, 2021, they are almost identical to McVeigh’s views: an obsession with gun rights, a belief in violence, a claimed kinship to the Founding Fathers. Exploring Timothy McVeigh’s story today shows how his views survived and flourished in the age of the internet, decades later.

2. Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols insisted on finding scapegoats for their reality.

Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols were both distinctive individuals, but they both led lives that were representative of larger themes and trends in American life. This is especially true in the development of the right wing.

“He was someone who didn’t blame the people who ran the companies, but blamed the government, that it had turned on him.”

Timothy McVeigh grew up outside Buffalo. His father worked at a GM plant in a town called Lockport for 30 years. His grandfather worked at the same plant for 30 years. At the time Tim McVeigh was growing up in the ’80s, that plant was shrinking, much like the Buffalo area around it. Tim McVeigh was living through the decline of industrial America and the shrinking of job opportunities.

The story of his political development is really the story of a search for scapegoats. He was someone who didn’t blame the people who ran the companies, but blamed the government, that it had turned on him. He embraced a right-wing philosophy that was centered around the protection of what he believed about the Second Amendment, the guns meant everything to him.

Later when he joined the army, he became much more fixated on race. He blamed Black people who he thought were jumping the line ahead of him. He also blamed women. He was, before this term was used, an incel, an involuntarily celibate.

His friend Terry Nichols, whom he met in the army, grew up outside in the thumb of Michigan. His life reflected the decline of agricultural America just as Tim McVeigh’s life reflected the decline of Industrial America. They both saw opportunities that their parents’ generation had disappearing before their eyes. Both of them turned to the military as a way of trying to escape their homes. For different reasons that dream did not turn out well for them either.

3. The internet is centrally involved in right-wing extremism.

One of the many haunting things that Timothy McVeigh said to his lawyers was, “There was an army out there, but I never found it.” What he meant by that was that there was an army of people who shared his extremist views but he could never figure out a way to find them and recruit them to his side. He went to gun shows, he sold The Turner Diaries, the dystopian novel that was such an important inspiration to him, and he listened to Rush Limbaugh, but he could never find the real allies and co-conspirators that he wanted.

“There was an army of people who shared his extremist views but he could never figure out a way to find them and recruit them to his side.”

In 2020, there was a plot to kidnap Governor Gretchen Whitmer of Michigan in October of 2020. The creators of that plot were from the Michigan Militia, to which Terry Nichols was also associated. The difference in the planning of the two events is that now, in 2020, co-conspirators in the kidnapping plan used the internet, using Facebook private chats to coordinate their plans.

If you look at all the right-wing extremism of today, the internet is centrally involved. Right-wing extremism and violence are therefore scarier now, as it is now easier for the people that McVeigh called “the army” to find each other and work together.

4. Though there were a slew of conspiracies, McVeigh and Nichols acted alone.

Did McVeigh and Nichols act alone? Was there a broader conspiracy? There had been rumors to that effect for years. People on the left often say that there was really a broader right-wing conspiracy. People on the right have tried to prove that there was foreign involvement, especially Islamic terrorists. Neither of those theories is true. McVeigh and Nichols did act alone. Evidence uncovered during the investigation and trial proves that this was the case.

One piece of evidence in particular holds a huge weight in the case. McVeigh and Nichols thought they were being very clever in hiding their long-distance phone calls. In those days, there were things called calling cards. They bought a calling card from a right-wing newspaper called The Spotlight, which they thought would never be uncovered. What that evidence showed was a record every time they made a long-distance phone call. From the period leading up to about a year and a half before the bombing to the bombing, the FBI could pinpoint every phone call and every call they made. They could pinpoint where they were making those calls from.

“McVeigh and Nichols thought they were being very clever in hiding their long-distance phone calls.”

We also know that there were no co-conspirators. Through those phone calls, there are records of how they tried to find all the ingredients, including the fuel, the fertilizer, and the infamous Ryder truck. All of that is in the calling card, but no other conspirators are in the calling card. This evidence suggests that McVeigh and Nichols acted alone.

5. Merrick Garland kept a low profile during the investigation of the bombing.

What was Merrick Garland’s role in the Oklahoma City investigation and what does it tell us about him as Attorney General now during the investigation of Donald Trump? At the time, Merrick Garland’s title in the Justice Department was Principal Associate Deputy Attorney General. In plain English, that means he was sent to Oklahoma City a day after the bombing to supervise the investigation.

At the same time, the OJ Simpson case was taking place also during April of 1995. Though the OJ trial was a national obsession, it was also a tremendous example to Garland of what the Justice Department should not do in the Oklahoma City investigation. He had, and has, a great aversion to public relations, and to public display. He did not want the kind of circus that the OJ case turned into. Thus, every step in the process was one he took to reduce the call of public attention.

That lesson is one he has carried forward to the Trump investigation. He has imposed on himself a burden of silence that is greater, frankly, than he needs to carry. He sees the role of the Justice Department as the role of the prosecutor, not as one of public education. It’s a debatable proposition about the Justice Department’s role, but it’s clearly the role that Garland saw in 1995 for himself. Therefore, it continues as the role he puts forth as Attorney General in the Trump investigation.

To listen to the audio version read by author Jeffrey Toobin, download the Next Big Idea App today: