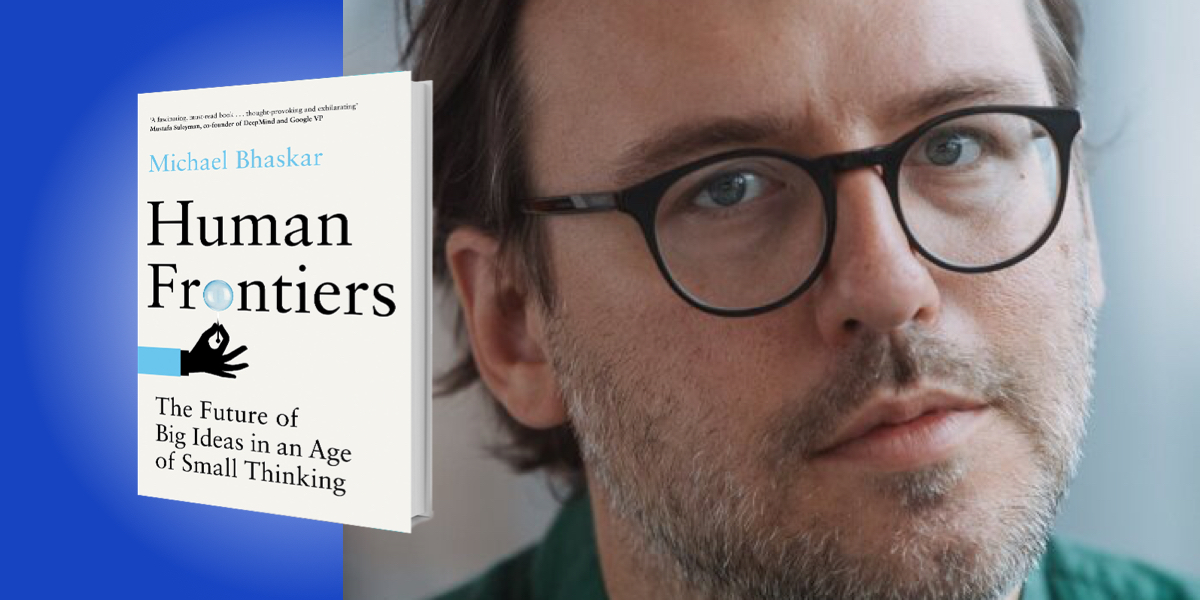

Michael Bhaskar is a writer, researcher, and cofounder of Canelo Digital Publishing. The author of Curation and The Content Machine, he spent two years as a consultant Writer-in-Residence at DeepMind, the leading AI research lab. He has been featured in The Guardian, the Financial Times, and on the BBC, among other media outlets.

Below, Michael shares 5 key insights from his new book, Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking. Listen to the audio version—read by Michael himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Some ideas matter more than others.

There are such things as big ideas, as opposed to any old, common idea. In general, people are a bit wary of things called “big ideas.” I think the world is somewhat hostile to them.

People tend to want to attack a big idea, or think that it’s somehow arrogant, or an imposition, or a myth. People want to say that big ideas break down into lots of little ideas. That is partly true. But the stuff of history is about big ideas—that which I call the “human frontier,” or the limit of what we can do. Maybe it’s our technological frontier, or the knowledge frontier of what we know about the world, or perhaps a cultural or artistic frontier.

A big idea is one that impacts at the frontier. And that’s not speculation, because a whole range of researchers have found ways to work out how much impact an idea has. You can then say, “Well, we can estimate the impact of every patent, and we find the top 5 or 1% that have the most impact. Those are big ideas.”

Then there’s also a psychological aspect. Some ideas just shock us. Darwin’s idea of natural selection was an explosive idea that pulled apart a lot of peoples’ worldview. Big ideas have this shocking, sensational impact.

Human history, human civilization, really doesn’t make much sense unless we have some awareness of those ideas that matter most.

“Human history, human civilization, really doesn’t make much sense unless we have some awareness of those ideas that matter most.”

2. There has been a Great Stagnation of big ideas.

Look around the world, and it feels like everything is going on. We have amazing new technologies launching. We have what seems like a really fast pace of change. How can it be called a Great Stagnation?

The phrase “Great Stagnation” was coined by Tyler Cowen, the economist, and quite a few other economists have now backed it up. The first piece of evidence would be that in the frontier countries—the most developed countries on Earth—economic growth has started to slow down on a long-term trend. In the middle of the 20th century, growth was faster than it is today. If we were a society that was accelerating into the future, why wouldn’t growth be accelerating? Even more than that, there is a productivity slowdown. Yet productivity tends to be driven by new technologies, so that suggests that big, new technologies are either not being rolled out as fast as in the past, or that something is not quite catching on about those technologies.

In essence, a lot of discourse on the Great Stagnation can be summed up by Peter Thiel’s quote, “We wanted flying cars, but we got 140 characters.” We got Twitter, not flying cars. If you compare now to the late 19th century, transportation does seem fairly stuck. If you were alive in the middle of the 19th century, you’d already have seen several revolutions in transport. You’d see the steam train, motorized boats, bicycles, then the motorcar, then the airplane.

In effectively the space of a human lifetime, you went from most people walking around and using horses, to humans landing on the moon in a massive rocket. It was an extraordinary transformation, and in each of these modes of transport was a big idea. Since then, all of those modes have become a lot safer, sleeker, cleaner, more efficient… but we’re not getting new ideas. There have been countless incremental improvements, but the big ideas that would transform transport seem to be stalling. There are lots of proposals for flying cars or drone delivery, but nobody’s actually getting them off the ground.

My idea of the Great Stagnation is broader than just economics and technology. I would say that when you look at our cultural world, it is stuck in a similar pattern. For most of the 20th century, you could clearly identify when music was from. Music from the 1980s sounded very different from the 1960s. There were new genres, new kinds of instruments, and whole new subcultures.

“We wanted flying cars, but we got 140 characters.”

Nowadays, there’s a lot of great music, but it’s not that different from 20 years ago. There’s not that kind of wholesale revolution in public taste that used to happen. There was a time in the 20th century when there were huge novelists, great philosophers, and they would dominate their fields. These huge ideas would come in, but it seems like big ideas are out of fashion.

Likewise, we’ve kind of given up on big new ideas about politics. When Francis Fukuyama talked about the end of history, he was talking about the end of massive new challenges to forms of political organization. And he seems to be right. We have a kind of reheated authoritarianism, we have liberal democracies, and we have a bit of a fudge between the two, but nobody has any clear idea what, if anything, might come beyond that. When you start to drill down, it does seem like there’s been a Great Stagnation of sorts. The big exception would be in digital technology, but it doesn’t invalidate the idea entirely.

3. It is getting harder to have big ideas.

There’s a huge amount of evidence for this from across a range of fields. A bunch of economists, for example, have shown that to maintain constant rates of technological progress, you have to pile in more and more resources. So, very concretely, very measurably, it is getting more expensive to have big ideas.

There are other ways in which it’s getting harder. The process of history is unidirectional, and there isn’t this infinite pool of big ideas. Once somebody’s instantiated one, then it’s done. It’s been taken. Without new tools or technologies or worldviews, the ideas have been taken to some extent.

There are limits to what technology can do. There are limits to what is economically feasible. There are limits to the human brain. It might be that in, say, physics, we are starting to approach the limits of what we can actually think. So, both in a measurable sense and also in the slightly more abstract sense, we are taking the low-hanging fruit, because we are getting close to the edge of some things. It adds up to a picture where, unless there are new breakthroughs that change things, it is getting objectively harder to have big ideas.

“To maintain constant rates of technological progress, you have to pile in more and more resources. So, very concretely, very measurably, it is getting more expensive to have big ideas.”

4. Society doesn’t like big ideas; small, incremental ideas are much safer.

If you look at businesses, they want a safe return. They don’t want to gamble huge amounts of money on something that is unlikely to generate a return. That’s even often true with venture capitalists and others who are supposedly taking all these risks.

Almost nobody can afford to back things that might fail for 20 years before they become good. There are many areas, by contrast, that used to have backing for big ideas. For example, you had a great ecosystem of innovation in mid-20th century corporate America, where in places like Bell Labs there was a huge amount of freedom. A lot of those places have been closed. And although tech giants do a lot of R&D, it doesn’t necessarily replace that real broad-based ecosystem.

So, we don’t give the timelines or the money. And secondly, a lot of the people coming up with ideas are at universities and other places where incentives for taking on the risks of a big idea just aren’t there. Scholars have to get citations. What gets cited? Well, it’s generally stuff that is already established. You have to calibrate what you pursue to what’s out there in order to get cited.

If you take a big risk with your career and get it wrong, you won’t get jobs, you won’t get tenure, and you won’t get citations. The entire sector of research and universities has been taken over by an almost bureaucratic box-ticking exercise, rather than what used to be free-blue-skies research. That kind of bureaucratic, safety-first, often intensely regulated atmosphere exists across institutions.

This dovetails with my point about funding. It makes for an incredibly conservative atmosphere for experimenting with big ideas—the ideas that seem ambitious and crazy, and will often fail.

The whole nature of what I’d call a series of populisms (from political populism to the need to get publicity) adds extra pressure. People are chasing eyeballs more than they’re looking for deep thoughts. The political atmosphere is polarizing opinions, such that there aren’t free spaces of investigation.

“People are chasing eyeballs more than they’re looking for deep thoughts.”

All in all, when you start looking into how research is done, how it’s funded, and how it’s discussed, you start to get a sense that society doesn’t like big ideas. Society would much rather have things that have somewhat the pattern of a big idea, but ultimately don’t really do much.

5. The Great Stagnation is likely ending, and powerful forces are likely to open new vistas of ideas in the next 20 or 30 years.

Right now we are building a new tool set that is by far the most powerful set of tools humanity has ever had at its disposal. Artificial intelligence is one example; DeepMind, the AI company, has effectively solved the protein folding problem, which was one of the longest-standing problems in biology. For 50 years, people have been trying to solve this, and not making much progress, but an approach that deploys cutting-edge machine learning techniques can solve it. So this is a new tool set of AI, encompassing everything from synthetic biology, CRISPR, nanotechnology, VR, and so on.

This new tool set is the outside factor that can change the way we see the world. It will change the ways we discover things, and the technologies we build. All of those tools are big ideas themselves because, if we deliver them, they’re the platform for the next hundred years of huge thinking.

The world is converging at the frontier for the first time in history. If you look at the frontiers of knowledge or technology, it has always been in a few localized societies or civilizations. A bit of Europe, or perhaps a bit of China or the Arabian Peninsula, but the whole world has almost never been working at the frontier at one time. The extraordinary economic growth around the world, and the nature of the internet, means that the capacity to work at the frontier is now global. Innovation isn’t going to be coming just from one corner. This has only come to the fore in the last 20 years, and it’s only now that we’re going to start feeling the effects.

If you put together this new set of tools and this great convergence at the frontier, then it creates the ingredients for a Great Acceleration. It provides enough momentum beyond the fact that society is hostile, beyond the fact that ideas are getting harder to generate. It means that we are entering a new phase—and that’s incredibly exciting.

To listen to the audio version read by author Michael Bhaskar, download the Next Big Idea App today: