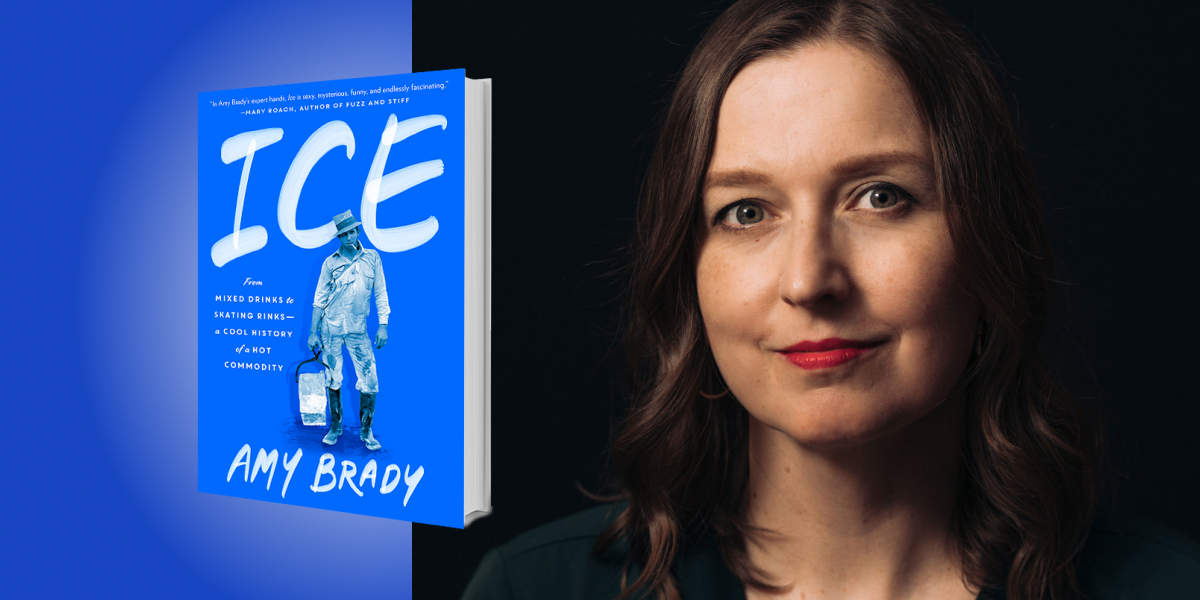

Amy Brady is the executive director of Orion magazine. She is also contributing editor for Scientific American and co-editor of The World as We Knew It: Dispatches from a Changing Climate. Brady has made appearances on NPR, BBC, and PBS. Below, she shares 5 key insights from her new book, Ice: From Mixed Drinks to Skating Rinks—a Cool History of a Hot Commodity. Listen to the audio version—read by Amy herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Never, ever give up.

The American ice industry began in 1806 when a visionary Bostonian named Frederic Tudor landed on the idea to carve blocks of ice from his Massachusetts lake and sell them for a profit to people in warm climates. His peers thought he was a madman for even considering the idea. How would he sell something as common and, well, free, as lake ice? How would he ship it long distances without it melting? Who would buy it—and why?

Tudor refused to listen to the nay-sayers and figured out how to build a cargo hold on a ship that would keep ice from melting. But the day the ship left the dock in Boston, a local paper ran a headline calling his endeavor a “joke” built on “slippery speculation.” When his ship arrived at its first stop in the Caribbean, it seemed like his critics were right. No one bought Tudor’s ice. It melted away, and Tudor went back to Boston empty-handed.

Over the next nine years, he attempted several more shipments, each one a dismal failure. He had to mortgage the family estate to keep his vision alive, and he even ended up in debtors’ prison—twice. Eventually, after building networks and implementing a marketing plan, he turned a profit. It took much, much longer to do so than he anticipated, but once the world caught up to his vision, they couldn’t get enough of what he was selling. Had he given up after the first, second, or even twelfth failure, Tudor wouldn’t have become an extremely wealthy man, and America wouldn’t have become the ice-obsessed nation it is today.

2. Your product isn’t just a commodity, it’s a lifestyle.

When Tudor first arrived in the tropics to sell ice, he struggled to sell it because people had never seen such a thing before—let alone knew what to do with it. It hadn’t occurred to Tudor that for people living in the tropics in the early nineteenth century, ice would have been as fanciful as a unicorn. He learned that he needed to demonstrate how his product could make life better—and more delicious.

He brought ice to every bartender and barista that would see him, showing them how to use ice in their drinks. Until this point, rum was served lukewarm, coffee was only served hot, and water was served the temperature of sweat. Tudor’s innovation was to change all that. He gave the bartenders ice for free so they could test whether their clientele enjoyed the icy concoctions. As it turns out, you can’t argue with a cold cocktail on the rocks. The icy drinks were a sensation. Bartenders and baristas started advertising them as luxury items to help beat the heat, and Tudor turned his first profit.

“As it turns out, you can’t argue with a cold cocktail on the rocks.”

Over the next several years, he would return many times to the Caribbean before setting his sights on New Orleans. There, he used the same marketing strategy. His cold cocktails were such a hit that New Orleans became not just an “ice city,” as Tudor called it, but a cradle of civilized drinking.

In just a few years, innovative mixologists in the Crescent City created the Sazerac and the gin fizz. Bartenders serving such drinks became celebrities. Ice became known as white gold. Ice consumption became a luxury lifestyle, and ice’s biggest proponents couldn’t get enough.

3. Sometimes the world must catch up to your vision.

In the 1850s, a doctor named John Gorrie drew on physics classes he took in med school to build America’s first ice machine. He was thrilled with his invention, but that’s not the response he received. Instead of cries of gratitude, he heard cries of blasphemy. Newspaper headlines called him a “crank.” How dare a man create ice? Only God can create ice!

On his deathbed, Gorrie wrote that his invention “has been found in advance of the wants of the country.” But the idea of creating ice didn’t die with him. A decade later the Civil War broke out, and the Confederacy was cut off from the northern ice shipments they’d come to depend upon. To replace that ice, they built giant ice plants capable of producing hundreds of tons of ice per day in major cities across the south—all of them built on Gorrie’s original blueprints. Those ice plants made ice more available than ever before. They brought the cost of ice way down, making it more affordable to average Americans. Eventually, the ice machine led the way for other innovations in medicine, such as cryotherapy, and in sports, with the indoor skating rink.

4. Adjust with the market.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Southland Ice Company was one of the largest mechanical ice companies in Texas, with stores across the state. The stores sold blocks of ice to customers who usually stopped by on their way to and from the grocery store. Some of the ice store managers noticed that customers often grumbled about forgetting key items on their grocery lists, like milk, bread, and fresh fruit. So, they started stocking such items alongside their ice.

“Customers often arrived low on fuel, so the company added fuel pumps.”

That proved to be a very popular decision, so they decided to make another change to accommodate yet another customer’s complaint: Customers often arrived low on fuel, so the company added fuel pumps. These changes made the stores so popular that the Southland Ice Company needed to extend their store hours to keep up with business.

The company eventually rebranded, naming its stores after their extended hours of operation, and 7-Eleven was born. By adjusting to what the market demanded, the Southland Ice Company combined kitchen staples, gas for the car, and blocks or bags of ice, all in one place, giving birth to an entirely new concept: the convenience store.

5. Get ahead by helping others.

In the summer of 1896, a deadly heatwave struck New York City. Temperatures rose to the nineties and stayed there for over a week. The city’s mayor and the state governor did nothing to help. By the time the heat dissipated, 1,300 New Yorkers had died.

Many more would have died if not for the swift thinking of a New York City police commissioner. He ordered hundreds of pounds of ice on dozens of wagons—whatever could be spared—to be delivered to the city’s poorest neighborhoods. Dozens of icemen and the commissioner himself unloaded the free ice and carried it into tenements, where people cried with relief.

In the months that followed, the people saved by the commissioner’s ice delivery became ardent supporters of his political ambitions. That commissioner was Theodore Roosevelt, and in just five years, he would be president of the United States.

To listen to the audio version read by author Amy Brady, download the Next Big Idea App today: