Dr. Akilah Cadet is the Founder and CEO of Change Cadet, an organizational development consulting firm. A Forbes Next 1000 Entrepreneur, Dr. Cadet also holds a Bachelor of Science in Health Education in Community-Based Public Health, a Master of Public Health, and a Doctorate of Health Sciences in Leadership and Organizational Behavior.

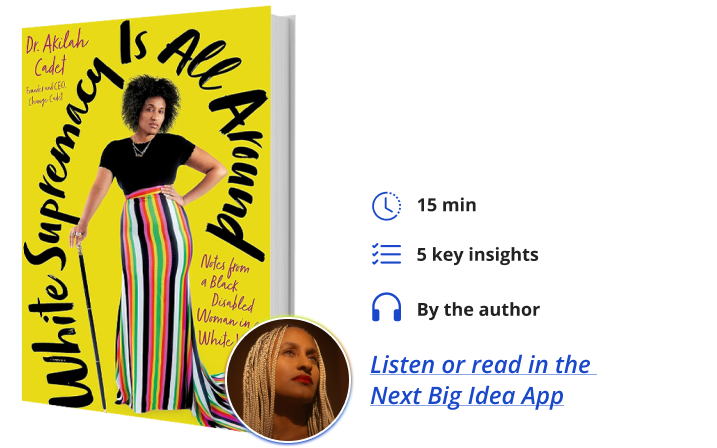

Below, Akilah shares five key insights from her new book, White Supremacy Is All Around: Notes from a Black Disabled Woman in a White World. Listen to the audio version—read by Akilah herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. White supremacy is not a bad thing.

You may be asking, why would a black disabled woman say that? Simply, it’s because when a white person drives down the street, they’ll get pulled over by a cop and may or may not get a ticket. They won’t be murdered or maimed or even get a ticket or wrongfully prosecuted like me. Their blood pressure won’t go up when an officer, cop, or sheriff drives by; they’ll be able to have the protection of white supremacy. It’s also a wonderful thing because when a white person goes into an emergency room, their pain is believed. They are treated, valued, seen, and heard. For me, this is not the case. As a Black disabled woman, when I go into the emergency room with rare conditions, I’m asked, “Are you anxious? Are you stressed out?” As a Black person, my pain is not believed, and I’m seen as a drug seeker. As a Black woman, my pain is definitely not believed.

We can also see this through childcare and healthcare in this country. White supremacy allows white women to be able to have babies in this country without thinking about who their doctor is. They don’t wrestle with having to prove their existence while in labor. They also don’t have to consider what to do if the doctor they built a relationship with isn’t there. If the doctor I worked with isn’t there, what happens if something goes wrong with me or the baby? If they are not feeling well, will I be taken seriously? Serena Williams would have hoped to be believed and cared for in the same way as a white woman. Black women suffer a rate of dying that is three to four times more than white women.

“White supremacy allows white women to be able to have babies in this country without thinking about who their doctor is.”

White supremacy is the ability to get a promotion without having to do a million jobs. It is the nine-to-five jobs that obligate employees to fit into a box. White supremacy is providing the structures, systems, policies, and practices for white people to thrive in this country.

Saying that white supremacy is all around is a way to acknowledge the importance of dismantling white supremacy, not for Asian American Pacific Islander supremacy, or not for Black supremacy. The goal is for all oppressed people—Black people, disabled people, women, non-binary people, the LGBTQ plus community—to receive the same as white people. That is dismantling white supremacy. On the whole, white supremacy is a great thing because white people who benefit from white supremacy can thrive and succeed in this country. They’re able to have that American dream without dealing with multiple layers of oppression.

2. Intersectionality is where our different identities cross paths.

Kimberly Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality, which refers to the intersections of our identities that make things great or not so great. Think about a bus going down the street full of people. At that first intersection, all the women have to get off the bus. At the next intersection, disabled folks would have to get off the bus. At the next intersection, all members of the LGBTQ+ community have to leave the bus. At the end destination of that bus, only heterosexual, cisgender, non-disabled white men would be left. This group currently has the most power, and the bus analogy demonstrates how white supremacy works in this country. The intersections are where people have to leave the bus, representing where folks don’t receive the same benefits as those who make it all the way to the end.

We need to understand intersectionality. My intersectionality occurs as a Black, disabled woman. I am always those three things. I’m always Black, as people can see my beautiful black skin. I am always a woman, and I identify as a heterosexual, cisgender woman. People can see my disability some of the time or not. It’s always with me because I have a dynamic disability; sometimes, I need an assistive device like my cane. Sometimes you see it, and sometimes you don’t, but I’m always in pain, and I’m always disabled.

3. We have to learn and unlearn continuously.

Learning is easy to understand because we’ve all gone to some type of school, whether we learn from our caretakers, parents, or school. We know how to learn, but we do not know how to unlearn. Unlearning is a challenge. Unlearning is realizing we all don’t know what we don’t know. Unlearning is realizing that what we thought was true is not.

An example is Columbus Day, now known as Indigenous People’s Day. Some people have been unlearning what they thought was right and true about Columbus. Unlearning involves understanding and acknowledging the genocide and horrible things that Indigenous peoples suffered upon Columbus’ arrival.

“Unlearning is a gift.”

Learning and unlearning is continuous. I’m a foremost expert in the world around white supremacy and diversity, but I’m constantly learning and unlearning. Unlearning is a gift. I have a little bit of the cheat code of experience because I am a Black, disabled person in this world. Therefore, I’ve had firsthand experience of more oppression. I’ve had to learn at a young age how to adapt to white dominant culture.

For example, in my preschool, there were two Black kids, and one was my twin sister. When my eighth-grade class graduated, there were about four black kids, and one was my twin sister. So, I was always part of the oppressed group and wasn’t part of the dominant culture. My lived experience granted me the tools early on to do more unlearning.

4. White supremacy is all around.

It’s in our textbooks. It’s at the hotels we stay at. It’s in the airport. It’s our jobs, the coffee shops, it’s everything and it’s everywhere. How are you using your power and privilege, knowing that white supremacy is all around?

Privilege is both earned and unearned. Unearned privilege is given to you. In the words of Lady Gaga, you were born this way. How did you come into this world? Did you grow up in a middle- or upper-class family? Did you have both of your parents? Did you have access to wealth? A house? Are you someone with a lighter complexion or are you one of the white ethnicities? How did you come into this world? Are you handsome? Are you beautiful? I have pretty privilege thanks to my parents. I know what my looks can afford me. When we think about our privileges—whether given through our DNA, caretakers, or parents—we can understand how to use that privilege for ourselves and other people.

Privilege is not just unearned. It’s also earned, too. Earned privilege is being able to acquire access to a company, a space, a learned language, a country, etc. You can either build off of your unearned privilege or do it yourself. So, for example, I was born with multiple rare conditions, but I wasn’t diagnosed with them until about seven years ago. So, for me, earned privilege is the protection of the American Disabilities Act. There are people who are born disabled, and that was part of their unearned privilege that was given to them. I’m still learning and unlearning what that means for me to be disabled in this country. I’m very proud to be disabled, but I’m also realizing that learning and unlearning involve advocating for those who are disabled. That ability to offer advocacy is centered around the fact that I am beautiful.

“How are you using your power and privilege, knowing that white supremacy is all around?”

As someone who is disabled, people expect me to look a certain way, talk a certain way, walk a certain way, or use a certain assistive device that deems me worthy of the earned privilege. I sit in the intersectionality of both visible and invisible disability. I use my privilege to advocate for my fellow disabled community. I use my power and privilege to help dismantle the myth around what disability looks like.

So, what are you doing with your power and privilege? How are you waking up every day, brushing your teeth, putting on your deodorant, checking your bias and your privilege? How are you advocating for yourself and others?

5. It is free-99 to apologize.

We are going to make mistakes. I make mistakes. But I have no problem apologizing for any harm that I have caused. I have no problem continuously learning and unlearning. I have no problem realizing that one person who may have similar intersectionality to another person can be completely different.

Apologizing is free-99. That’s a way to hold ourselves accountable so that we can act every day. Accountability, communication, and transparency are crucial. How am I holding myself accountable for what I’m saying and doing, moving past allyship? Allyship allows for comfort. To be someone who is an advocate, accomplice, and activist, apologies are a big part of doing the work. How am I communicating? How am I being transparent with how I feel?

Personally, I’m comfortable being uncomfortable. A lot of people are not comfortable being uncomfortable, regardless of how they identify. Realizing that an apology is free-99 is realizing that accountability, communication, and transparency can bring us to our goal. Getting comfortable with being uncomfortable allows us to do the work needed to dismantle white supremacy.

You have a choice of how you show up every day, and that choice can dismantle white supremacy. All oppressed groups can have the same thing as white people, or we can choose to further perpetuate and uphold the system as it is.

To listen to the audio version read by author Akilah Cadet, download the Next Big Idea App today: