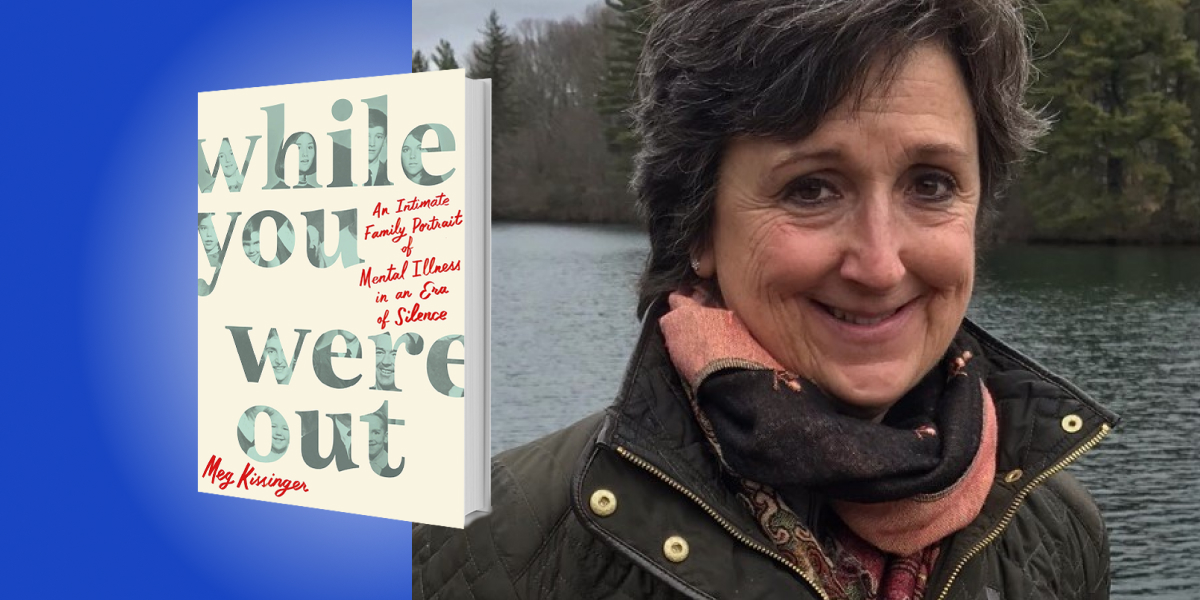

Meg Kissinger is an award-winning journalist for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. She is A Pulitzer Prize finalist and has won dozens of accolades, including two George Polk Awards, the Robert F. Kennedy Award, awards from Investigative Reporters and Editors, and two National Journalism Awards. Kissinger teaches investigative reporting at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism and was a visiting professor at DePauw University, her alma mater.

Below, Meg shares 5 key insights from her new book, While You Were Out: An Intimate Family Portrait of Mental Illness in an Era of Silence. Listen to the audio version—read by Meg herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The mental health system is not a system.

It’s a sieve that allows millions of sick people to fall through its many holes. The definition of a system is “a set of things working together as parts of a mechanism.” When it comes to mental health, almost nothing works together. If you’ve ever tried to get help for yourself or someone you love, you know this.

We don’t have enough doctors to care for the huge numbers of people who are suffering. More than half of counties in the United States lack a single psychiatrist. Even if you are able to find a doctor, paying for good mental health care is out of reach for most people. Insurance companies often deny claims without merit. They set the reimbursement rate for psychiatric care so low that many doctors say they cannot afford to take insurance and will only accept patients who can pay out of pocket.

Can you imagine denying treatment to someone with a suspicious lump or stabbing chest pains? Yet, this happens thousands of times every day for people with crippling depression, panic attacks, or terrifying delusions. Many have no clue where to turn for help. In the twenty-five years of reporting on our country’s broken mental health system, I was most haunted by the frantic parents who called me wondering how to get help for their sick child, because I had no good answer for them.

So what happens to these very sick people who can’t get medical care? The lucky ones likely will recover on their own in time. But 58 million Americans suffer from serious mental illness, a distinct category meaning a lifetime of chronic disease. That subset is about 5.6 percent of all people with mental illness. People with serious mental illness get confused easily. They’re often overwhelmed. They may have a hard time sleeping, making decisions, holding a job, staying in relationships, making their own meals, paying their bills, and caring for other basic needs. Some are not able to separate fantasy from reality or even recognize that they are sick. When they are left untreated, many end up abandoned on the streets, or dead.

2. People with mental illness are human beings.

That might sound overly obvious or even facetious. But when you consider how people with psychiatric illnesses have been treated throughout history you will see why this point cannot be underscored often enough.

Those with illnesses like schizophrenia, mania, and depression were once thought to be evil, possessed by demons. Witch doctors bore holes in their skulls to release the wicked spirits. Beginning in the 1600s, so-called healers figured the veins of people with mental illness were full of bad blood. So, they cut holes in their bodies and covered the sores with leeches. This blood-letting was meant to rid the patient of bad humors and restore the body’s balance. That didn’t work well either.

By the late 1800s, the preferred treatment was isolation. Governments began building asylums with foreboding names on the outskirts of town where the city folk need not have to see or think about those unfortunates. To keep them docile, patients were kept behind locked doors where they were sometimes submerged in ice baths, injected with insulin, doped up with sedatives, and chained to their beds. Many were confined to straight-jackets. Lobotomies, popular in the 1940s and 50s, were performed by hammering an ice pick into the eye socket of the patient to sever the connection between the prefrontal cortex and the frontal lobes.

“The federal government promised to close down the old asylums and build robust community care.”

In Milwaukee, where I live, county workers used to cut off the arms and the legs of those who had died at the Asylum for the Chronic Insane so they could save money on the wood for their coffins. It was only after World War II when conscientious objectors who were assigned as orderlies in state mental hospitals leaked photographs of this barbaric treatment to the press that the public could see the grisly reality of how many chronically mentally ill people lived. Those exposes led to the new era of deinstitutionalization. The federal government promised to close down the old asylums and build robust community care.

The idea was to divide each county into catchment areas, like congressional districts, where community mental health centers could offer an array of services from in-patient care for the sickest to out-patient medication dispensaries and clinics for classes on stress management, postpartum recovery and life skills training. “When carried out, reliance on the cold mercy of custodial isolation will be supplanted by the open warmth of community concern and capability,” President John F. Kennedy said as he signed the 1963 bill to overhaul mental health care in America. Three weeks later, Kennedy was gunned down in Dallas. The enthusiasm for reform died with him.

The federal government emptied the asylums and tore down the buildings, but reneged on its promise to provide community care. More than half of the community centers that were planned were never built.

3. We need to listen to people with mental illness.

Given that grim history, it’s little wonder why so many people are too frightened or ashamed to acknowledge that they have mental illness. We make them feel like it is their fault that they are ill, like it’s a character flaw, a moral failing, or their parents’ fault. Even today, we refer to people with psychiatric diseases as “schizophrenics” and “the mentally ill,” like they are some kind of lesser form of human, worthy of being described only by their illness. The truth is, some of the sickest people I interviewed over the years were also some of the cleverest, funniest, and most generous I’ve ever met.

People with mental illness have a double burden—they are sick and hurting but often they have to suffer alone because no one around them can or wants to listen to them. They don’t get casseroles or flowers or get-well cards. Is it any wonder then, that the suicide rate is at an all-time high? In the past twenty years, as the rate of deaths from heart disease and cancer declined significantly, the rate of suicide jumped a staggering 37 percent. After a brief dip during the early days of the pandemic, the number of people dying by suicide is expected to reach an all-time high by the end of the year. Nearly 50,000 Americans will die by their own hand in 2023.

“People with mental illness have a double burden—they are sick and hurting but often they have to suffer alone because no one around them can or wants to listen to them.”

Suicide is now the second-leading cause of death for children ages 10 to 14 and people between the ages of 20 and 34. Disturbing as it may be, feeling suicidal is a shockingly common human emotion. In 2021, 12.3 million Americans seriously considered killing themselves, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention estimated. About a third of those people said they had an actual plan and nearly two million put their plans into action.

The week before he died, my brother Danny sent me a letter describing what it was like for him to live with chronic mental illness. “This is an awful disease,” he wrote. “Only love and understanding can conquer it.” Those words seemed cheesy to me when I read them then, not knowing they were the words of a man who would soon be dead. In the years since I’ve reflected on them a thousand or more times. And I see that Danny was exactly right. If you love someone, you will try and understand them. And, if you understand them, you will try to help them. You will listen to them.

If we are going to cut down on the alarming number of suicides, we need to let our friends and families talk about their thoughts without making them feel ashamed. We need to be able to ask,

“Are you feeling like hurting yourself” with the same clarity and sense of purpose that we would about chest pains or trouble breathing. We need to find a way to let them have their voices be heard. Silence can be deadly. Shame kills.

4. Families need support, too.

For every person who lives with serious mental illness, there are family members who are affected, too. We feel the anguish of watching our loved ones languish. Jobs lost. Relationships severed. Lifelong goals unfulfilled. We mourn the death of the lives that we thought they were going to have. Every now and then, I run into one of my sister Nancy’s friends or someone who knew Danny and I think, what more could I have done to help them so they’d still be here?

There is a lot we can do on a micro-level to help ourselves and the people we love who are suffering. Join a support group. Find healthy ways to blow off steam. Talk about it!

In 2006, I was diagnosed with breast cancer. The hospital staff swarmed me with support. The ladies auxiliary knit me hats to keep my head warm when my hair fell out from the chemo. They assigned me someone they called a “journey coordinator” if I needed help getting to an appointment or keeping track of my medication. I was lucky enough to have a loving husband and two great kids to help me. But do you know who needs journey coordinators? People with serious mental illness and their families.

“We do better when we share our lives with one another.”

A note here to all those struggling with their own mental health: Ask for help. Let me tell you about my older brother Jake. Jake was diagnosed with crippling depression back in his college days. He now lives in a group home for people whose mental illness is so pronounced that they cannot live on their own. Jake, amazingly, has the humility to reach out to us when he is feeling shaky. He is not too proud to say that he struggles or to ask for help. This, I believe, is his saving grace. Jake knows that the key to feeling better is to be with the ones he loves. We are social animals. We do better when we share our lives with one another. To quote one of my favorite Beatles songs: “In the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.”

5. Despite all your hard work and care, the person you love might still lose the battle. Take heart in knowing you did all that you could.

This is true of all illnesses—cancer, heart disease, diabetes. That’s hard to hear, but it’s true. Sometimes the illness is so catastrophic that the person simply cannot be saved. If you’ve done all that you could and they die anyway, try and find comfort in knowing that you did your best.

I spent decades haunted by the question of what more could we have done to stop our sister and brother from killing themselves. The night that my sister Nancy died, my father called us all into the living room and instructed us, in no uncertain terms, “If anyone asks, this was an accident.” That was on a Friday night. By Tuesday, we were back in school or at our summer jobs, business as usual. Move along, now. Nothing here for you to see.

I worried that our silence around Nancy’s death set the stage for Danny’s. Families of people who kill themselves are more than twice as likely to die by suicide. What if we would have gotten the help that we so desperately needed? How much more grief could we have spared ourselves? No one can say for certain. It’s never too late to reach out for help. Decades later, I finally got the chance to ask those questions.

In the wonderful poem “In Blackwater Woods” Mary Oliver talks about the devastation of a forest fire and what can come in its aftermath. “Look, the trees are turning into their own pillars of light, giving off the rich fragrance of cinnamon and fulfillment,” she writes. That’s what having the chance to talk about the mental illness in our family has done for me and my brothers and sisters. We’ve become our own pillars of light, finding ways to help each other.

Oliver ends her poem with this genius advice, words that now give me great comfort:

To live in this world, you must do three things:

Love what is mortal

Hold it against your bones

Knowing your whole life depends on it

And when the time comes to let it go

To let it go.

To listen to the audio version read by author Meg Kissinger, download the Next Big Idea App today: