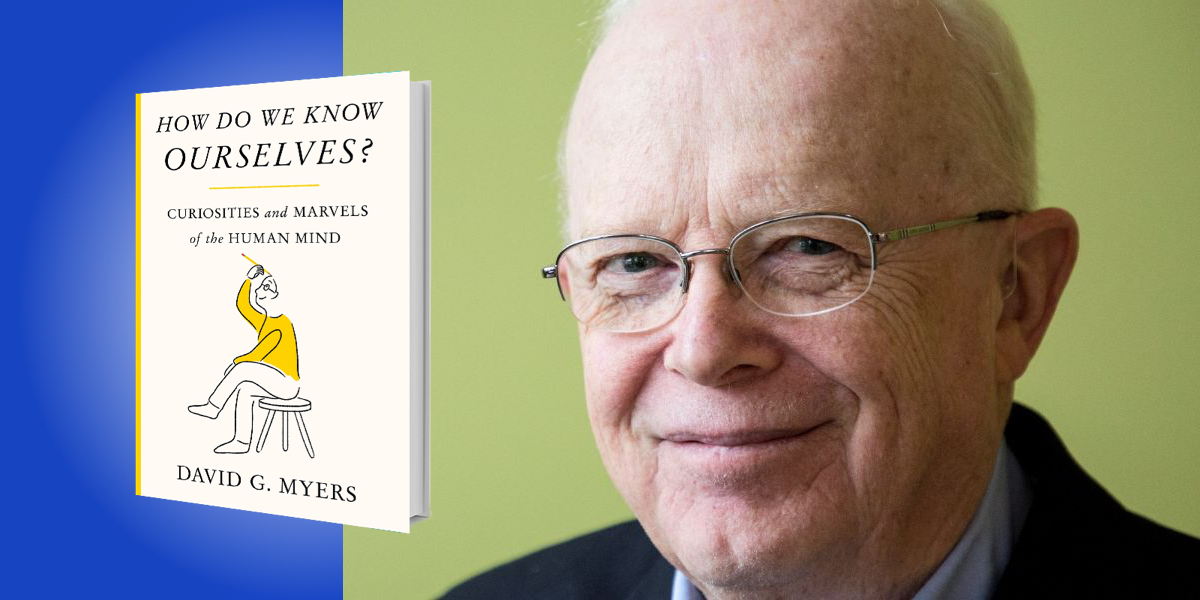

David Myers is a research psychologist at Hope College where he reads and reports on the wonders of human thought and action.

Below, David shares 5 key insights from his new book, How Do We Know Ourselves?: Curiosities and Marvels of the Human Mind. Listen to the audio version—read by David himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Our expressions and actions are self-revealing.

Much as when we observe others and infer their sentiments, so hearing ourselves talk clues us in to our own attitudes. Witnessing our actions signals how strongly we feel. “Self-knowledge,” said Goethe, “is best learned not by contemplation, but by action.”

The surprising extent to which this is true becomes apparent in some clever experiments. In one, Swedish participants spoke one word while occasionally hearing their own voices saying another word. On two-thirds of these trials, they experienced the inserted word as what they spoke.

Other experiments have manipulated facial expression. Researchers may induce a scowling expression by asking participants to pull their brows together, under the false pretense of attaching facial electrodes. People felt a bit angrier. Likewise, if manipulated into a smiling expression, people felt happier and found cartoons funnier. As the father of American psychology, William James, discerned in the late 19th century, going through the motions can trigger the emotions. “To feel cheerful,” he advised, “sit up cheerfully . . . and act as if cheerfulness was already there.” To empathize with someone else, mirror their expressions and synchronize your movements with theirs.

Or try for yourself what folks in another experiment did: Take a short walk with shuffling steps and eyes downcast. Then return with long strides, arms swinging, and eyes straight ahead. Can you feel the difference?

2. The happy power of micro-friendships.

Recall brief conversations with strangers that left you feeling cheerful—perhaps after providing directions to someone on the street. Fleeting interactions can brighten other people’s day, and your own, to a surprising degree.

In one experiment by Nicholas Epley and his University of Chicago colleagues, commuters were offered a $5 gift card to either A) Do as they normally would on their train or bus, B) Sit in solitude, or C) Strike up a conversation with a stranger. Participants in the third condition presumed the attempted conversation would be awkward, but it seldom was. Moreover, they were in a happier mood at the end of their ride. Other experiments have revealed a similar mood boost among people who banter with a barista or compliment a stranger in passing.

“Fleeting interactions can brighten other people’s day, and your own, to a surprising degree.”

Small acts of kindness have been found to make both the giver and receiver feel better, to a greater degree than expected—even for introverts. I asked my own friends if they could recall happy experiences of humanizing yet brief interactions, either as giver or receiver. Dozens of heart-warming replies flooded in. Many recalled the happy results of reaching out to homeless people, grocery store clerks, tradespeople, taxi drivers, fellow hikers, dog-walkers, or just the person ahead of them in line.

So push beyond your comfort zone! Go out of your way to chat up the rideshare driver. Ask the checkout clerk how their day is going. Check in with an old friend. You will brighten their day—and yours.

3. We often fear the wrong things.

We fret about vividly publicized but highly improbable horrors while ignoring greater risk. Dramatic catastrophes make us gasp while we barely grasp statistical probabilities. Thus, we may fear airline flights more than driving—even though over the last decade, driving has been, per mile traveled, 501 times more likely to result in death.

Or consider COVID. In a Gallup World Poll of more than 100,000 people, 39 percent of those over 65 were “worried about their health under COVID.” But among those aged 18 to 29, despite having more than a hundred-fold lower death risk, a similar 40 percent expressed COVID fears. Moreover, fully vaccinated people—who have little to fear—are more likely to fear the illness than unvaccinated people, who are at risk of serious harm.

How many parents agonize about statistically rare terrorist acts, school shootings, and child abductions, while not bothering to strap their child into a car seat? Whatever makes national news is, by definition, rare—and thus something that, though horrific, poses less of a risk than life’s undramatic, ongoing threats. Consider the 40,000 lives taken each year (100+ per day) by suicidal, homicidal, and accidental gun deaths.

“Dramatic catastrophes make us gasp while we barely grasp statistical probabilities.”

If we care about minimizing tragedy, we should not let feelings hijack thinking. Next to the evil of a school shooting, statistics seem cold. But exaggerated fears of infinitesimal risks do their own harm. Numbers matter, risk statistics matter, because the real risks to lives everywhere matter—for those we know and with whom we empathize, and those unseen and in the future.

4. Differences seize our attention.

As social psychologist William McGuire noted long ago, we are conscious of ourselves “insofar as, and in the ways that” we differ. When he and his co-workers invited children to “tell us about yourself,” they mostly mentioned their distinctive attributes. Redheads volunteered their hair color, foreign-born their birthplace, minority children their ethnicity. In the U.S., a Pew survey found that 74 percent of Black people but only 15 percent of white people see their race as “extremely or very important to how they think of themselves.” Differences determine our spontaneous self-concepts.

In my daily life, surrounded by mostly white colleagues and neighbors, I am seldom mindful of my race—which becomes a prominent part of my identity when visiting my daughter in South Africa, where I become part of a 9 percent minority. In Scotland, I’m self-conscious of being American. To be in a numerical minority is to become more conscious of that identity.

At times, our acute self-consciousness has funny consequences. In one of social psychology’s more creative studies, researchers used theatrical makeup to place an ear-to-mouth facial scar on college women—supposedly to see how others would react. After each woman checked the real-looking scar in a hand mirror, the experimenter applied “moisturizer” to “keep the makeup from cracking”—but they were actually removing the scar.

So a woman, feeling terribly self-conscious about her supposedly scarred face, would talk with another woman who knows nothing of this. If you have ever felt similarly self-conscious—perhaps about a physical handicap, acne, or a bad hair day—then you can sympathize with the woman. Compared with women who believed their conversational partners merely thought they had an allergy, the “disfigured” women became acutely sensitive to how their partners looked at them. They rated their partners as more tense, distant, and patronizing. Observers who later analyzed videotapes of how the partners treated “disfigured” persons could find no such differences in treatment. Self-conscious about being different, the “disfigured” women had misinterpreted normal mannerisms and comments.

“To be in a numerical minority is to become more conscious of that identity.”

Consider, also, a clever experiment in which Cornell University students were asked to don a dorky Barry Manilow T-shirt and were then shown into a room where several others were completing questionnaires. Afterward, participants estimated that about half of the others noticed their dorky attire, when only 23 percent actually did.

This spotlight effect—an overestimation of others’ noticing us—extends to secret emotions. We presume that our attractions, disgust, and anxieties become visible. If we’re nervous, will our face show it? Not necessarily. Even lies and lusts are less transparent than we imagine.

There’s bad news here: Others notice us less than we imagine, partly because they are more worried about the impressions they are making. But there’s also good news: Others notice us less than we imagine. This is liberating: A bad hair day hardly matters. Few will notice. Fewer will care. Of those, fewer still will remember.

5. Hindsight bias is powerful.

If these insights seem familiar—like something you knew all along—then I beg you to consider one of psychology’s underappreciated lessons: Anything seems obvious, once it happens. After the stock market drops, we recognize that it was due for a correction. After the football game, we fault a losing coach for the stupid play call. After an election, its outcome seems predictable. How easily we presume that we knew more than we did. As philosopher Søren Kierkegaard recognized, “Life is lived forwards, but understood backwards.”

Hindsight bias has a way of making history seem like a series of inevitable events, when in actuality the future is seldom foreseen. No one’s diary reads, “Today, the Hundred Years’ War began.” Thus, after the 9/11 attack, investigators found signals that made the disaster seem obvious. But in the six years before 9/11, the FBI’s counterterrorism unit could hardly have pursued all 68,000 uninvestigated leads, and only in hindsight did the few useful ones become obvious. Nevertheless, because outcomes, once known, seem predictable, we tend to blame decision-makers. After the sudden and chaotic Afghanistan government collapse, pundits (who never predicted such) disparaged President Biden for not having foreseen it.

Moreover, we blame not only others for “stupid mistakes,” but also ourselves. Looking back, we realize how we should have handled a person or a situation. “I should have known how busy I would be and started that project earlier.” “I should have realized sooner that he was not to be trusted.” “I should have known not to risk money on that stock.” But sometimes we are too hard on ourselves. We forget that what is obvious to us now was not nearly so obvious at the time.

As Sherlock said to Dr. Watson, “It is easy to be wise after the event.”

To listen to the audio version read by author David Myers, download the Next Big Idea App today: