Jonathan Marks is a professor of politics at Ursinus College. Marks describes himself as an “exotic bird” because he is a conservative academic in the dominantly liberal industry of higher education. Marks writes for conservative outlets like Commentary Magazine and the Wall Street Journal.

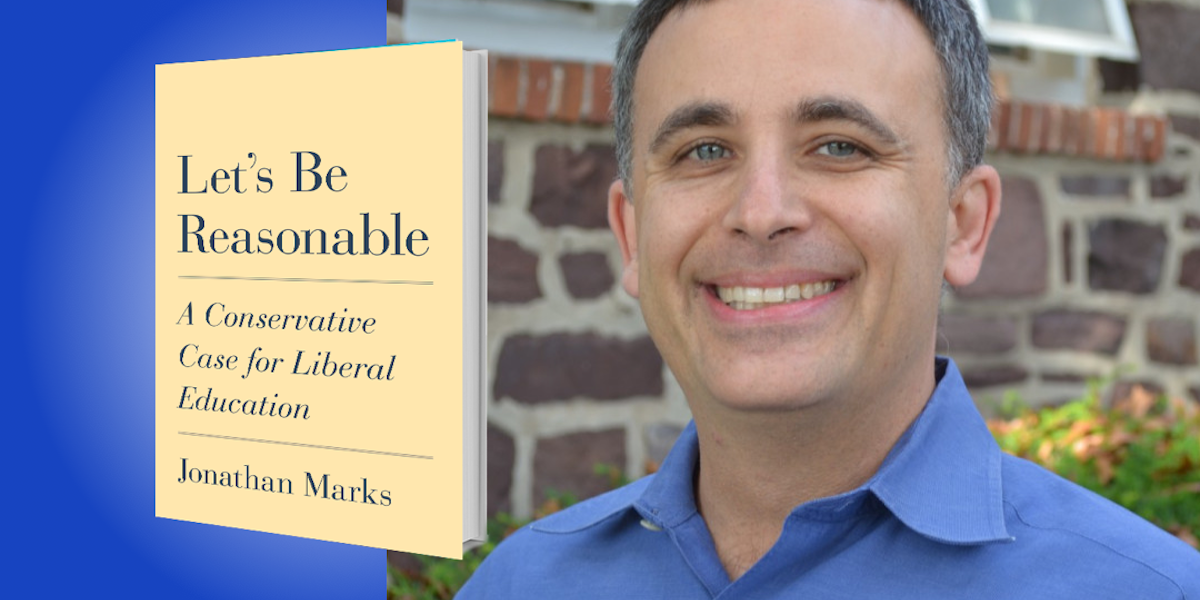

Below, Jonathan shares 5 key insights from his new book, Let’s Be Reasonable: A Conservative Case for Liberal Education (available now from Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Being reasonable is not just a skill set.

Colleges and universities are in the “reason” business, which is why college and university leaders are always going on about critical thinking. Liberal education aims to shape reasonable people, but reasonable people aren’t merely (or even mainly) possessors of a box of critical thinking tools. Shills, hyperpartisans, and bullshitters possess such boxes too.

John Locke, the 17th-century educational and political philosopher, said, “There cannot be any thing so disingenuous, so misbecoming a gentleman or any one who pretends to be a rational creature, as not to yield to plain reason and the conviction of clear arguments.” He has in mind a type of person we all know—one who, when confronted with undeniable evidence against his position, changes the subject, insults his opponent, or admits he’s wrong today, but then returns to the same argument next morning. If we were to grab that person by the collar and plead with them to “Be reasonable!” we wouldn’t mean, “Take a class on critical thinking!” We’re not dealing with someone who doesn’t know what an argument is. He may even be more skilled than we are at arguing, but cares more about sticking to his guns than he does about the truth. When we say, “Be reasonable,” we mean, “Let’s stop playing around.” We mean that reason is an authority, not a tool to get the better of others.

There’s a set of standards within which a community of reasonable minds can productively wield their reasoning skills. Conduct unbecoming a reasoner includes an approach in which reason isn’t authority. It’s a standard that suits a community of people who seek the truth together. A liberal education aims to draw us into such a community and to bring us around to such a standard.

2. It’s not that bad for conservatives in academia.

Many people think that conservative professors and students are persecuted. Early this year, we heard from a Princeton student writing in the National Review that even George Will, a mild-mannered, anti-Trump political commentator, was deemed too controversial to be invited to campus by a Princeton debating society. “Stalin lives at Princeton,” declared a conservative journalist. It’s clear to students that conservatives are regularly exorcised out of academic settings.

“Reason is an authority, not a tool to get the better of others.”

Yet this same debating society had, months before, hosted Ted Cruz. Not long before that they had Ken Buck, a Colorado congressman who made news upon releasing a video in which he brandished his AR-15 while daring Joe Biden to come and take it from him. So while the George Will story makes the university look bad if true, if someone paid for an exorcism at Princeton, they should ask for their money back.

It’s just one story, but it’s representative of the potential on liberal campuses for the voices of campus conservatives to be silenced. It’s very likely that conservatives are in the minority because liberal academia is overwhelmingly leftist, thanks to people’s desire to hire those who resemble them, inadvertently discriminating against diverse worldviews. But it’s also true that in surveys, conservative professors indicate that they are as satisfied with their jobs as liberal professors are.

Joshua Dunn and John Shields wrote a book, Passing on the Right, based on interviews with conservative professors. Respondents generally told them that the Academy has far more tolerance than right-wing critics of a progressive university imagine. At the same time, surveys also indicate that conservative students are more reluctant than their liberal counterparts to speak about controversial issues. That said, the difference is overblown (you’d think from the media coverage that it was a kazillion percent).

I don’t claim that all is well for conservatives at universities—far from it—but I object to the overbroad, overheated sense of victimhood that now prevails in our circles, which saps energy that might otherwise do some good.

3. Liberal education is not just for elites anymore.

In 1995, Earl Shorris assembled a class that consisted almost entirely of students living at or below 150% of the poverty threshold. Some of his students were homeless. Some had been in prison. Some could barely read a tabloid newspaper. All studied with Shorris, and other instructors, the same kinds of ideas they would encounter in a first-year course at Harvard, Yale, or Oxford.

“I object to the overbroad, overheated sense of victimhood that now prevails in our circles.”

Shorris describes what happened after those students were presented, early in the course, with a difficult logic problem. In a short time, his students had formed a community of reasonable people, trying to arrive at a solution by weighing the arguments. Liberal education is sometimes thought of as a luxury good. But if it aims to shape reasonable people, it’s not a luxury good at all. What we’re doing, when we weigh the arguments, is trying to keep our minds in order. John Locke calls “understanding” the last resort a person has recourse to in the conduct of himself. He says that every man carries about him a touchstone to distinguish truth from appearances. That touchstone is natural reason, a noble faculty possessed by men of study and by the day laborer.

Everyone has an interest in making use of better principles in matters that greatly concern them. My students aren’t like Shorris’ students, but they’re mostly middle-class people, not the products of expensive prep schools, and more likely to go into K–12 teaching than management consulting. They are also capable of undertaking and benefiting from liberal education. And after all, do we really want to say that the future teachers of our children ought not to pursue the comprehensive enlargement of mind, that Locke says the reasonable person pursues?

4. Students aren’t angels, and students aren’t demons.

An old, higher-ed joke has it that being a professor would be terrific were it not for all the students, but no teacher can afford not to try knowing the complex people whom they teach. That is, however, hard. Teachers, like everyone else, are prejudiced—subject to confirmation bias, the tendency to look for and interpret evidence in accordance with our views and overconfidence. It is therefore disheartening how often professors and higher education writers proclaim in one breath the importance of not supposing one knows, when one doesn’t know, and then declare that today’s students are part of generation W, X, Y, Z, from which much is supposed to follow.

You may have heard that today’s students are against free speech, but their attitudes towards speech are complicated. In a 2018 survey commissioned by the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, a majority of students agreed that colleges and universities should be able to restrict student expression of political views that are offensive to certain students. But an even larger majority said that students should have the right to free speech on campus, even if what they were saying offends others. So, your guess is as good as mine. You may have heard that today’s students are obsessed with safety because they were coddled as children, but data from the Monitoring the Future survey suggests that today’s students are no more risk-averse than students in my own Generation X, who I can assure you rode beltless in the back of station wagons and ran to school alone with scissors.

“Most good work on any campus is not accomplished by screaming bloody murder.”

Today’s college students are neither paragons of social justice, nor crybabies who should be given a stern lecture about what real hardship is. Like students before them, they have the capacity and the motive to become reasonable. Colleges should cultivate that reasonability.

5. It takes five to make an enormous difference.

The Princeton political philosopher Robert George inspires this idea. George is a social conservative, and social conservatives are more on the outs in academia than your average conservative bear. Yet George says it really doesn’t take a hundred professors to make an enormous difference on campus—it only takes five. Two decades ago, George founded the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton as a forum for the vibrant, robust discussion of the spectrum of points of view that are held by reasonable people. Those include conservative views. At my own Ursinus College, there were around that same number of people, five, who began to develop our common intellectual experience for a genuinely liberal education. Thanks to those five, every first-year student who has passed through in the past two decades has read great books like Plato’s Euthyphro and Genesis, which encourage reflection on enduring questions like how one should live. Once a model like that has been developed, it can be adopted at other places.

It’s easy to despair over never being able to change anything in our vast higher education landscape, especially when every ill-conceived, left-wing op-ed written for the student newspaper is boosted by conservative commentators with large followings. You may not have heard of the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions, but thanks to the National Review, you may have heard of a Princeton student who complained about how other students making fun of how he pronounced “Cool Whip” constituted a microaggression.

It’s easy to despair because conservative complaints about our politicized campuses have more than a little truth in them—but there is much to be done by teachers, in whose classrooms students learn to confidently follow arguments and evidence where they lead. Meanwhile, administrators are in a position to nurture the commitment to reason that is already present on their campuses. Then there are organized groups, like the Foundation for Individual Rights and Education or the Heterodox Academy, which have seen great success fighting for free speech by reasonable people on campuses. Most good work on any campus is not accomplished by screaming bloody murder, even though it’s a rush, and may even win you some fans. It takes time and patience to build a diverse following that can even include people with whom we differ on many issues. It may take courage, but it doesn’t take an army. It takes five.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: