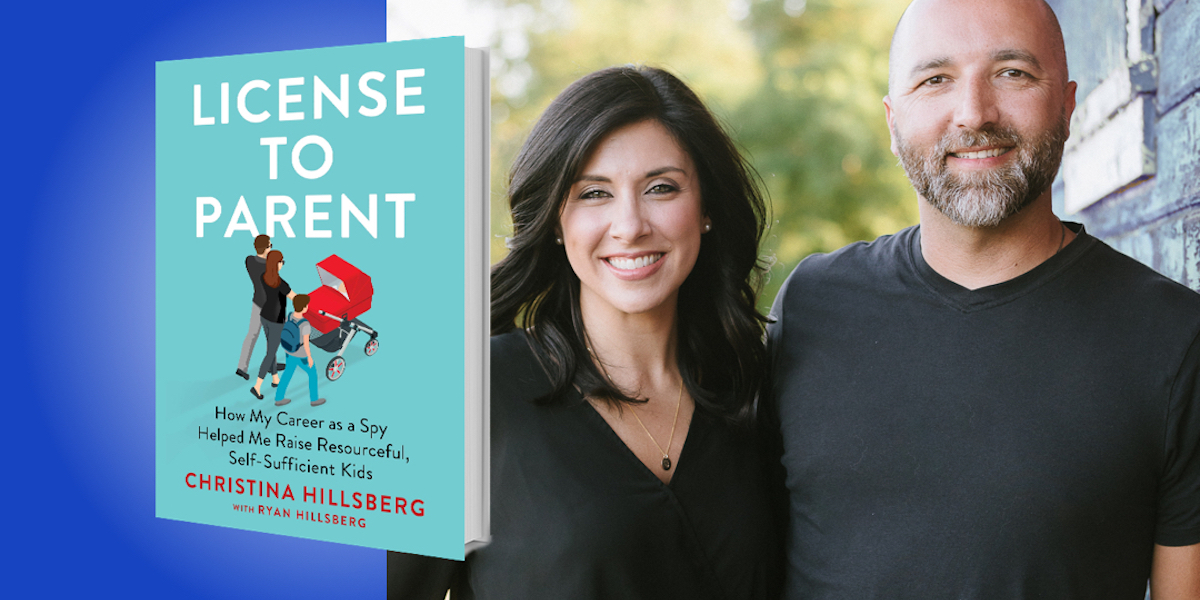

Christina Hillsberg is a former CIA intelligence analyst, a writer, and a mom. Her husband, Ryan Hillsberg, is a former CIA operations officer, the current Director of Corporate Security at a global biotech company, and a dad.

Below, Christina and Ryan share 5 key insights from their new book, License to Parent: How My Career as a Spy Helped Me Raise Resourceful, Self-Sufficient Kids (available now from Amazon). Listen to the audio version—read by Christina and Ryan themselves—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Teach your kids how to spot and avoid danger.

Ryan: There was a stark reality I faced when I first became a father: I’m not able to be with my kids at all times to protect them and keep them safe. Because of this reality, I want to know that I’ve done everything possible to prepare them so that they have the best chance at avoiding danger, surviving dangerous scenarios, and defending themselves if necessary. As part of this endeavor, we teach our kids a concept that we learned at the CIA called “get off the X.” The X can be anything: a person, a car, a building, an environment—literally any situation in which danger rears its ugly head and your gut tells you to run. The bottom line is you want to get as far away from the X as you can. The longer you stay on the X, the more likely that you’ll be harmed.

One of the most important lessons you can teach your kids is how to spot danger, and so much of that has to do with listening to their Spidey sense. Teach your kids to tune in to the feeling they get when the hairs on the back of their neck stand up—this can be a useful barometer for when they should get off the X. When emergencies happen, it can become chaotic quickly, and it’s common for people to become “frozen.” It’s important to register what’s happening as quickly as possible so that you can keep moving, as opposed to freezing in place as events unfold around you. Teaching your kids to visualize how they would react in potential “get off the X” situations beforehand and mentally preparing for how they would keep moving can make all the difference.

“It’s extremely important for our kids to know that just because someone is an adult doesn’t mean that person is always right.”

Kids are never too young to start learning these concepts. On the contrary, shielding kids from these realities can do them a disservice, because it doesn’t prepare them for the real world. When teaching this concept to your kids in age-appropriate ways, we’re empowering them, rather than frightening them.

2. Emphasize the importance of thinking critically to your kids, even if that means ignoring authority figures.

Christina: Something we learned time and time again at the CIA is the importance of thinking critically. It’s good to ask questions, even of authority figures. We recommend teaching your children that there’s a time to do what’s asked of you, but if it doesn’t seem right, don’t be afraid to push back—respectfully, of course. And surprisingly, sometimes the concept of getting off the X may actually be the opposite of what you’re instructed to do. There are times when it’s not only appropriate but also critical to ignore orders from authority figures.

You may be familiar with the sinking of the Japanese-built South Korean ferry known as the Sewol ferry disaster. On the morning of April 16, 2014, the ferry sank, and 304 of the total 476 passengers and crew aboard the boat perished. Many of those who died were secondary school students. News media reported that as the ship sank, a voice over the intercom told passengers not to move because it was dangerous. Given that many were children, they were likely frightened and inclined to follow orders. Some of those who jumped or ran to the top of the ship were rescued. Those who stayed did not survive.

It’s extremely important for our kids to know that just because someone is an adult doesn’t mean that person is always right. As your children become older, they must learn to think critically for themselves and to question authority. If they already have a foundational understanding of these two things, they’ll be more inclined to think for themselves in an emergency scenario.

“In order to connect with someone on common interests, it’s important that you have a portfolio of your own genuine interests from which to draw.”

3. Expose your kids to a variety of interests, skills, and topics.

Christina: At the CIA, we approached targets and developed relationships using the “You Me, Same Same” approach. This is all about finding common ground to create an immediate connection with someone, which you can then build on to convince them to agree to a clandestine relationship with the CIA. In order to connect with someone on common interests, it’s important that you have a portfolio of your own genuine interests from which to draw. That’s why it’s important to emphasize well-roundedness for your kids as early as possible—they should know something about everything and everything about something.

One of the best ways to teach your kids this concept is to model it. Ryan, for example, speaks four languages, plays multiple instruments, enjoys a variety of sports, cooks and bakes from scratch—the list goes on. With this impressive portfolio of skills and interests, he can pull from just about anything when meeting someone. It wasn’t just common interests on which we connected on our first date, though; I was drawn to him because his array of interests fascinated me. This fascination continued when I met his kids, and it was clear that he had also instilled the concept of well-roundedness in them. To be honest, I hadn’t met any kids under ten who knew how to ride motorcycles, shoot arrows, and ski.

You can instill this concept in your kids too, and you can begin by exposing them to a variety of skills as early as possible. Consider skills that may be useful, as well as topics that interest them. You may consider things like archery, motorcycles, sailing, hiking, camping, cooking, athletics, computer programming, music, crafting, and more. These don’t have to be abilities that you have yourself; you can find a class for your kids to take alone if they’re interested, or you can take up a new interest together. Seeing you learn something new with them can demonstrate that it’s never too late add to your repertoire. When you ensure your kids have a variety of interests, you’re filling their tank with endless topics for building relationships with others throughout their lives.

“We’d rather expose our kids to technology while they’re young and living with us, so that we can guide them if and when they make a mistake.”

4. When it comes to technology, strike a balance between autonomy and boundaries.

Ryan: When people find out that we’re former spies, they often assume that we must spy on our kids. Perhaps surprisingly, quite the opposite is true for our family. Some parents opt to install surveillance software on their kids’ devices, but we’ve chosen not to do this. Instead, we seek to strike a balance between giving them autonomy and boundaries. We’d rather expose our kids to technology while they’re young and living with us so that we can guide them if and when they make a mistake, rather than restrict their access only for them to stumble when they’re out of the house. Moreover, if we restrict their access, we’re taking away opportunities for them to become more skilled and knowledgeable.

When it comes to cell phones, for example, we want our kids to have some freedom so that they can strengthen social skills and stay connected to their friends, especially when we’ve been isolated due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We also want to build trust through giving them more and more responsibility. That said, we want to set them up for success and not failure, and that’s where the boundaries and expectations come into play. In addition to controlling the installation of apps, we also put screen time limits on their phones, so if they want extra time, they have to send a request from their phone to ours.

In our home, we try to find a balance between giving our kids access to apps that we feel are appropriate and saying no when we feel, for whatever reason, that they’re not ready. Again, it’s about balancing boundaries and independence, and considering each app for each child on a case-by-case basis. We’ve made it clear to our kids that if we’ve told them they can’t have a particular app, that doesn’t mean we’re not open to changing our minds with the right persuasive argument and data points. However, an argument that hinges on “But this app is so in right now!” or “Everyone has it but me” will not get them anywhere. Instead, we ask them to answer the following questions:

- What do you want?

- Why do you want it?

- How will you use it?

- What impact will it have on your daily life?

- How do you envision this changing your life in the short and long term?

- What opportunities will this app give you?

If they can answer these questions respectfully and convincingly, then they’ve just argued their way into an additional app. If instead they’re complaining or being rude, then nothing will change, and we won’t approve access. Just like choosing what level of supervision you’ll have on their cell phones, this will be a personal choice for your family. Find an approach that works and, ideally, it’s one that emphasizes trust so that if and when your child makes a mistake, they feel comfortable seeking your guidance.

“We don’t have to be rock stars or failures. We can fall somewhere in between, and in the best-case scenario, we walk away well-rounded and better because of it.”

5. Show your kids what failure and determination look like.

Christina: You should set them up for success, knowing that they’ll sometimes fail. When they do, be there to help them learn from their mistakes. In fact, they’ll learn the most from mistakes. This is an approach the CIA often takes in its training, knowing that once we’ve failed at something, we’re unlikely to make that same mistake again. They’d rather failure happen in training than during an actual intelligence operation. Similarly, we’d rather our kids try new things and learn how to fail while they’re young, so that they don’t make the same mistakes again and they don’t fear failure.

At a young age, I began avoiding new things if I thought I might not be good at them—or worse, that I’d fail miserably. It’s only been since becoming a parent that I’ve made a significant effort to change this about myself. Why? Because I don’t want my kids to fear failure. I think of all of the things I haven’t tried over the years, specifically how I’ve robbed myself of opportunities to learn new hobbies and sports. Maybe I would have been good at some of them, or maybe not—but the world is not black and white. We don’t have to be rock stars or failures. We can fall somewhere in between, and in the best-case scenario, we walk away well-rounded and better because of it.

In my effort to discover new interests, I decided I wanted to learn how to wake surf behind our boat. I tried to surf nearly every time we went on the boat that summer, often for an hour at a time, falling again and again. But I kept swimming back to the board and calling out, “Ready!” as Ryan revved the engine for another go. Each time, I told myself that I was doing this to show the kids that (1) it’s okay to not be good at something, (2) you’re never too old to try something new, and (3) when we fall in life (quite literally, in this case), we get back up and try again.

How can you model failure and determination for your kids? Is there something new you can try either together or separately? Show them what it means to push through something that doesn’t come naturally. Encourage them to try something that, perhaps, doesn’t play to their strengths. You may not realize it now, but demonstrating lessons like this—and giving them opportunities to do the same—while they’re young can have a big impact on how they approach new hobbies and interests throughout their lives.

To listen to the audio version read by Christina and Ryan Hillsberg, download the Next Big Idea App today: