Indra K. Nooyi served as CEO and chairman of PepsiCo from 2006 to 2019. She was the chief architect of Performance with Purpose, the company’s mission to deliver sustained growth by making more nutritious products, limiting the company’s environmental footprint, and empowering its associates and people in the communities it serves. She has been awarded the Padma Bhushan, India’s third-highest civilian honor, the U.S. State Department’s award for Outstanding American by Choice, and 15 honorary degrees.

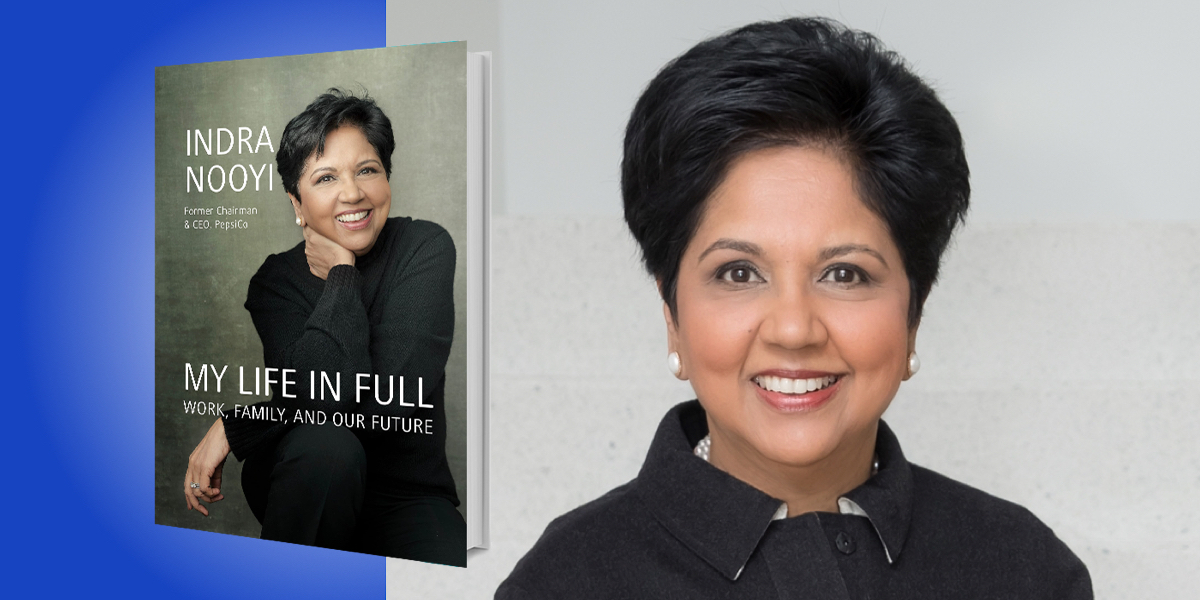

Below, Indra shares 5 key insights from her new book, My Life in Full: Work, Family, and Our Future. Listen to the audio version—read by Indra herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The accelerator and the brake.

I was born just eight years after India’s independence from the British, and the country was trying to figure out its identity as a new democracy. Social change was happening in our household, too. I was supremely lucky that the elders in our house—my parents and my grandfather—wholeheartedly embraced girls and boys as equal. They were completely focused on our education, and my sister and I had every chance to study and soar. This was not an obvious or easy path, especially for my mother. She had one foot on the accelerator—encouraging us to dream big, quizzing us after dinner on world leaders and the great rivers, and expecting top grades. She hadn’t had the chance to go to college after high school because her family didn’t have the money for her, as a girl, to do so, and she wished for us the opportunities she never had.

But our busy Hindu Brahmin household, with aunts and uncles and cousins coming and going, was also fairly conservative—and there was constant chitchat and poring over horoscopes to consider who the girls might marry at age 18. My mother worried about that, too. She had her other foot on the brake, concerned that I was an energetic, outspoken girl who loved to climb trees and started a rock band, and that I wouldn’t become the gentle wife, mother, and daughter-in-law that our community expected and admired.

“We need women to do both—to rise in the paid economy and to be mothers.”

All the millions of women who have entered the workforce in the last fifty years are emerging from an era of one foot on the accelerator and one foot on the brake. The march to women’s equality is still new, and we must encourage it so that girls everywhere can go to school, and women can choose to go to work. At the same time, it’s a reality that women bear the children and lead in caregiving. I believe we must let both of these realities flourish. We need women to do both—to rise in the paid economy and to be mothers. In other words, it’s time to take that foot off the brake.

2. India and the U.S.

I came to the United States at age 23 to attend Yale. At first, everything about being in Connecticut was new and strange. The roads were wide and clean, traffic was orderly. It was quiet. The greenery all around was spectacular. I loved it.

At the same time, I struggled to understand many aspects of day-to-day life. I had to learn how to shop in a self-serve grocery store. I was aghast when my classmates didn’t stand when a professor entered the room. I was sheepish about my clothes, and shy about whether I could wear a sari to a job interview. But soon, as is the case with so many immigrants to the U.S., I found my place in this country that is founded on a great idea—that we can come from anywhere, live together, and succeed.

I am still Indian—I am the girl who grew up in India, the world’s largest democracy. But I am also American—someone who improbably rose to run an iconic company that celebrates the American spirit. I belong in both worlds, and I think my journey was only possible in this country. Much as we may question ourselves and despair over the divisions in the United States right now, I stand firm that the U.S. truly captures meritocracy like no other. It is still the most open and welcoming country in the world, and we should celebrate what we’ve got.

“I stand firm that the U.S. truly captures meritocracy like no other. It is still the most open and welcoming country in the world, and we should celebrate what we’ve got.”

3. Power and humility.

One December night in 2000, I was at work when I got a call from Steve Reinemund, PepsiCo’s new CEO. He told me that I was being named president of the company, and would join the board of directors. I was over the moon. I packed up and drove home, and when I walked into the kitchen—there was my mother. “I’ve got the most incredible news!” I exclaimed. “The news can wait,” she said. “I need you to go get milk.” I turned around, went out and got the milk, and, when I came back, I was hopping mad. “I was just named president of PepsiCo, and I’m joining the board, and you couldn’t just let me share my big news,” I declared. “Listen to me,” she said. “I don’t care if you are president or on the board. I don’t even know what that is. But when you come through that door, you are a wife, a mother, a daughter—and no one can take your place in this family. So you leave that crown in the garage.”

I have told this story hundreds of times, and I still think I should have been able to share my news. But I also know my mom was right; the stability of our home meant I would be equally valued and important, whether or not I had been named president of PepsiCo. And that stability was a source of pride for her, too. Inside the house, I was just me.

I think that if I were a man, a husband, a father, I would have had more leeway. Men seem to be allowed to celebrate their work achievements without always being reminded that they have responsibilities at home, too. Women, not so much. Her comment also pushed me to think more about power and humility. Those of us who are privileged to lead must remain firmly rooted to the ground, and focus on the responsibilities of the job. This can be tough—the trappings of being a CEO, for instance, are extraordinary. The connections and experiences can be dazzling. The scope of the job is also grueling. I sometimes struggled to be cheerful at home when I was worrying about decisions that would affect PepsiCo’s earnings or global markets. I was also a little bit hurt when I gained stature at work, and some members of my extended family started treating me like I was no longer the same person. But in the end, I tried to compromise and remember what centered me and where I came from. My mom was right: No matter who we are—women or men—we all have to leave our crowns in the garage.

4. Performance and purpose.

When I stepped up to lead PepsiCo in 2006, I knew it was incumbent on me to connect what was good for our business with what was good for the world. The company had to last well beyond me—it needed to be “futureproofed.” I read all I could about the megatrends that could impact the corporation over the next 10 to 15 years, and I concluded that the way forward was to transform PepsiCo. We would create a balanced portfolio that included treats and healthy eats, become much more environmentally conscious, and ensure that all of our quarter-million employees felt supported and proud of our work and their contribution. “Nourish, replenish, cherish,” I told people thousands of times.

“I am a capitalist, and I believe in markets, but I also believe that companies are part of society and must be a force for good.”

I called this mission “Performance with Purpose.” This was not corporate social responsibility, where we take the money we earn and put it toward good works. There is a role for that. Instead, PwP was about changing the way we made money. As a publicly traded company, we had to deliver for shareholders—but I felt strongly that we also had to responsibly serve and support consumers, customers, suppliers, and the communities in which we operated. I am a capitalist, and I believe in markets, but I also believe that companies are part of society and must be a force for good.

5. Work and family.

When I started this book and finally had time to read the volumes of excellent research on why women have such a tough climb in the work world, one matter became very clear to me: There is a disconnect. The people in the rooms of real power—who are almost all men—do not talk about “family” as a driver of global progress. They don’t dive into the intricacies of women’s roles in the economy, or discuss how to support young family builders or how to ensure we have thriving populations going forward. In those rooms, “family” is fringe. Women—and much of what half the population does and thinks—are on the outskirts.

I believe we have to elevate “family” into the global conversation in a whole new way. We can no longer just talk about it on the sidelines at women’s gatherings, or only in policy, budget, or finance conversations in the context of social programs. “Family” must be central to how we talk about the future of work. We know our current work-and-family structure is weak and vulnerable. We saw this during the pandemic—more than 2 million women in the U.S. left the workforce. Meanwhile, we saw care workers, cleaners, nurses, and teachers sacrifice for all of us as “essential workers” during the crisis.

I believe we have sidelined so many people in our economy—especially women—because we haven’t created the right support systems for contemporary life. We have to do more. I’m not speaking just as a feminist here, but as an economist. We are living in a very ambitious world—we are tackling climate change and poverty, inventing new technologies, building infrastructure, making art, and learning to live in a more global and diverse community than ever before. We need all hands on deck to prosper together. I think we also need paid leave. We need to take what we have learned about work flexibility in the last two years and create new patterns that give workers more agency over their time.

As a business leader who has designed and led massive transformation, I know we can change our companies and communities. We can create a more inclusive, supportive, productive economy. It’s within our grasp. As that Chinese proverb says: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.”

To listen to the audio version read by author Indra Nooyi, download the Next Big Idea App today: