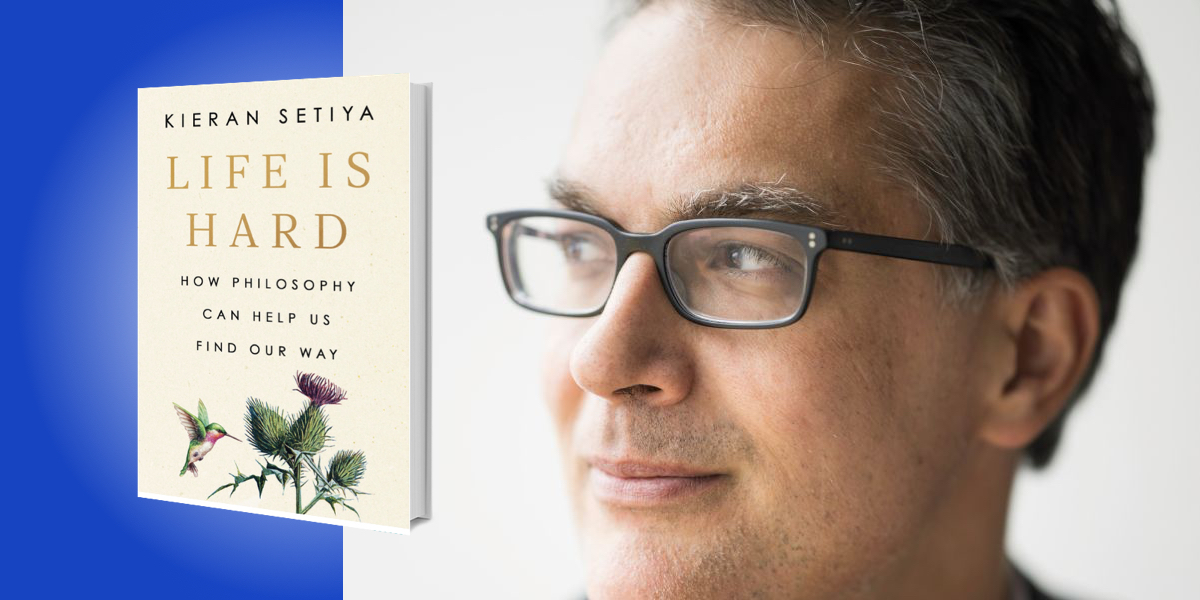

Kieran Setiya is a professor of philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Below, he shares 5 key insights from his new book, Life Is Hard: How Philosophy Can Help Us Find Our Way. Listen to the audio version—read by Kieran himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Acknowledgement comes first.

Here’s an experience you may have had: You tell a friend about a problem you are coping with, maybe a blowup at work or in a close relationship, or a health scare that has you rattled. They are quick to reassure you or to offer you advice, but their response is not consoling. Instead, it feels like disavowal: a refusal to acknowledge what you’re going through. What we learn in moments like these is that assurance and advice can operate as denial. What we need in our affliction is acknowledgement.

Philosophical reflection here is as much about attending to adversity as it is about arguing around it. As the novelist-philosopher Iris Murdoch wrote: “I can only choose within the world I can see, in the moral sense of ‘see’ [that turns on] moral imagination and moral effort.” Paying attention to what’s happening in someone’s life, finding the right words to describe it, isn’t just consoling in itself. Often, it’s the better part of knowing what to do.

2. Don’t try to be happy; try to live as well as you can.

Who doesn’t want to be happy? At the end of the day, you might think, it’s happiness that matters most; it’s the reason for everything we do. Being happy is not the same as living well, though. Happiness is a mood or feeling, a subjective state; you could be happy while living a lie. We can illustrate this with a thought experiment, riffing on The Matrix. Imagine Maya, submerged in sustaining fluid, electrodes plugged into her brain, being fed each day a stream of consciousness that simulates an ideal life, the only real inhabitant of a virtual world. Maya doesn’t know she’s being deceived; she is perfectly happy. But her life does not go well. She doesn’t do most of what she thinks she is doing, doesn’t know most of what she thinks she knows, and doesn’t interact with anyone or anything but the machine. You wouldn’t wish it on someone you love, to be imprisoned in a vat, alone forever, duped.

“The unhappiness of grief or anger at injustice aren’t things we would be better off without.”

The truth is that we should not aim to be happy but to live as well as we can. I don’t mean we should strive to be unhappy, or be indifferent to happiness, but there is more to life than how it feels. The unhappiness of grief or anger at injustice aren’t things we would be better off without. In living well, we cannot extricate justice from self-interest or divide ourselves from others. Our task is to face adversity as we should—and truth is the only means. We have to live in the world as it is, not the world as we wish it would be.

3. Value the process.

At the age of 35, I had a premature midlife crisis. Life seemed repetitive, empty, just more of the same: a sequence of accomplishments and failures stretching through the future to decline and death. I would finish the paper I was writing; it would get published, or not; I would write another. I would teach these students; they would graduate and move on; there would be more. All of it worthwhile, in its way, but somehow hollow and self-defeating.

My problem was being too project-driven. When we pursue a project like earning a promotion, getting married, or having a child, satisfaction is always in the future. The moment that project is achieved, it’s already in the past. Worse, by aiming at completion, we’re aiming to extinguish an activity that gives meaning to our life. Once the project’s done, we have to move on; what next? No wonder the present feels empty, like we’re sprinting to stay in place. Borrowing jargon from linguistics, we can say that projects are “telic” activities—aimed at a terminal state, fulfillment always in the future or the past, activities for which success can only mean cessation.

“By aiming at completion, we’re aiming to extinguish an activity that gives meaning to our life. Once the project’s done, we have to move on; what next?”

Not all activities are like this. Some are “atelic,” and they don’t aim at a terminal state of completion. As well as walking home, there’s just going for a walk, with no particular destination. As well as having a child, there’s the ongoing work, and joy, of parenting. For me, it’s thinking and talking about philosophy, which has no permanent end. It’s not that results don’t matter, because they do. But if we invest in the process, too, what we value isn’t extinguished by our engagement with it; it isn’t archived or deferred, but fully realized in the present.

4. Life is not a story.

It’s often said that we do, and should, narrate our lives to ourselves in living them, the heroes of our own stories. It’s less often recognized how much we risk in doing so. In practice, those who think of life as a narrative gravitate to narratives of the simplest and most linear form. That linear form is the idea that one aspires to tell the story of one’s life as a single integrated arc, a quest.

It’s not necessary, however, and it’s not a good idea. By squeezing your life into a single narrative tube, you set yourself up for definitive failure. Projects fail and people fail in them. We have come to speak as if a person can be a failure—as though failure were an identity, not an event. When you define your life by way of a single enterprise, a linear narrative, its outcome will come to define you.

Yet there is more to any life than a single story. The more you appreciate the sheer abundant miscellany of life, the more you’ll see it as an assortment of small successes and small failures. You will also be less prone to say, despairingly, “I’m a loser”—or with misplaced bravado, “I’m a winner!” Don’t let the lure of the dramatic arc distract you from the digressive amplitude of being alive.

5. Do one thing to fight injustice.

Chances are, you spent some time today on the internet, doomsurfing—skipping from headline to headline in a daze of horror. Click once to see energy prices spiraling; click again for the faltering of democracy; a third time for glaciers melting as climate chaos grips the world. Most of us click with a sense of guilt and shame. The superficiality of surfing deadens our emotions, and the scale of the world’s crises leaves us feeling overwhelmed.

“It’s wrong to disregard the increments.”

In the face of such realities, what are we to do? “The almost insoluble task,” the philosopher Theodor Adorno wrote, “is to let neither the power of others, nor our own powerlessness, stupefy us.” The proper response to paralysis is not inaction; it is to take the first step. Do one thing.

I am not much of an activist, let alone a leader, and I feel routinely overwhelmed by the injustice of the world. If that resonates with you, my advice is to pick a single issue and find a group that you can join. For me, the issue was climate change and the group was Fossil Free MIT. In 2015, the student group pushed MIT to enact its first ever Climate Action Plan. We couldn’t persuade the Institute to divest from fossil fuels—but we did something.

Confronted with the scale of human misery, some despair. They believe it doesn’t matter what they do, or that millions will still suffer regardless. This thought is confused. You may not do enough, but the difference you make when you save a life is the same whether you save one of two or one of two million. A protest may not change the world, but it adds its fraction to the odds of change. It’s wrong to disregard the increments. We make the same mistake when we deny ourselves compassion, knowing that others suffer more. “It may be the most important lesson I ever learned,” the poet Richard Hugo wrote, “maybe the most important lesson one can teach. You are someone, and you have a right to your life.” You also have a right to your suffering.

To listen to the audio version read by author Kieran Setiya, download the Next Big Idea App today: