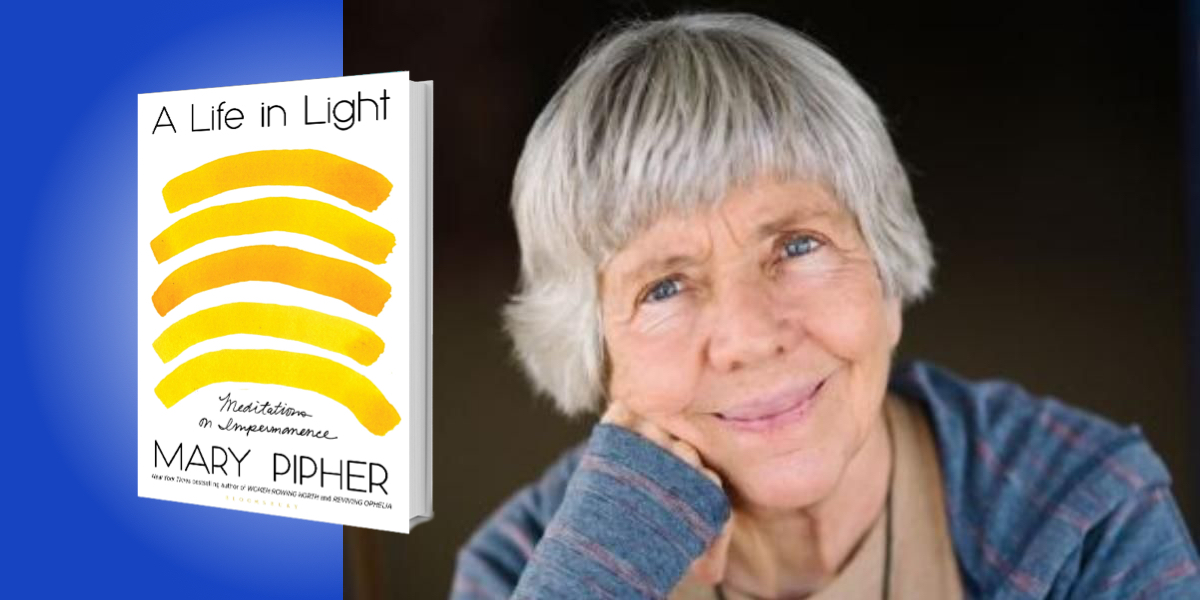

Mary Pipher is a clinical psychologist, community activist, and author of 10 books, including the New York Times bestseller Reviving Ophelia. Below, she shares 5 key insights from her new book, A Life in Light: Meditations on Impermanence. Listen to the audio version—read by Mary herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Our lives consist of a continuous interplay of light and shadow.

Thomas Edison was born in 1847, and I was born a hundred years later in 1947. He invented the light bulb on October 21st, which happens to be my birthday. Light is my joy and my medicine—it’s my first memory. When I was an eight-month-old baby, someone carried me out in the Ozarks into my grandmother’s front yard. I was lying on a blanket and looking up at light sparkling through the tree above my head. I have that memory encoded. Even though it’s not verbally encoded, it’s encoded as light and shadow.

Everything changes constantly. What is here now will soon transform. There’s a Japanese word that perfectly expresses this concept: komorebi is the dance of light and leaves as the sun shines through them. Metaphorically, it signifies the melancholic longing for a person, place, or thing—in other words, the inescapable human experiences of poignancy and loss.

When we are small, it may be the loss of a pet, a grandparent, or the beloved kindergarten teacher we must say goodbye to when summer comes. As we age, we lose people. By our 70s, we are attending more funerals than weddings, saying goodbye to siblings and close friends. Yet we all have moments in the sun. Even after a funeral, we can walk outside, hear the song of a cardinal, or see the hibiscus blooming.

I have a story about a cat that lived on our property. This cat was scroungy, three-legged, and didn’t look strong. My grandson burst into tears when he first saw him. I’m not sure how this cat managed to catch birds or survive. But one day I was sitting on my porch, and this cat was lying on our driveway, just wriggling around on the pavement with his belly up to the sun. I realized that even the hungry three-legged cat has days in the sunshine.

2. Happiness is a choice and skill set.

Two of the most important skills are setting intentions and feeling gratitude. Being grateful is not a virtue—it’s a survival skill. And attitude isn’t everything, but it’s almost everything. Sunlight is a metaphor for joy, but also for rescue. When we are struggling, we can look for the lighted path forward. For me, this is both a literal and metaphorical statement.

“Being grateful is not a virtue—it’s a survival skill.”

For example, from the time I was two until I was five, my family lived in Denver. My parents were rarely around. My father, who was based at Fort Fitzsimmons, served as a medic in the Korean War, and my mother was attending medical school at the University of Colorado. We lived in a tiny house on a dirt road in the small village of Aurora. My two younger brothers and I were left with a series of indifferent housekeepers. We were lonely, feral children, but I was deeply attached to my mother. When she was home, I barnacled myself to her.

One Saturday night, she took us driving on the plains of eastern Colorado. My brother, Jake, spotted the KOA radio tower, and we drove over to see it—but we found something much better. There was a splashing fountain that changed colors. We sat on the warm hood of our car, stars above, with air smelling like sage and prairie grass. I watched those sparkling lights cascade. My mother got back in the car and fell asleep, my brothers wrestled on the ground, but I was entrenched by those beautiful lights. I held them in my memory all the way home. That night, I learned the trick of preserving a moment: watch carefully, take in everything, and vow to hold that moment forever. I found this particular skill very useful all of my life.

3. To be happy, we must balance sorrow with beauty and joy, and despair with meaningful work.

After sad events, I found that listening to certain classical music melts the frozen rivers of my heart and allows me to grieve. After the school shooting at Sandy Hook, I was numb with pain. I tried to figure out how I could calm down. Eventually, I realized I needed to go outside and let the entire night sky absorb my sorrow.

Unfortunately, it was a cold winter night. I put on my coat, hat, and gloves, got a sleeping bag, and lay down on my driveway, looking at the stars. After a long while, I felt like I was in the presence of a sky that could absorb everything.

Work is also an antidote to despair. My mother had a saying: “The cure for everything is salt. The salt of hard work—sweat—the salt of tears, and the salt of the open sea.” I believe what she meant by “the salt of the open sea” was moving to a different place for a new perspective. Though she also could have meant the beauty of the open sea.

“The cure for everything is salt. The salt of hard work—sweat—the salt of tears, and the salt of the open sea.”

When I’m feeling low, I try to figure out a useful job for myself. That always cheers me up. One thing I commonly do is call someone I know will be happy to hear from me. I’ve got an old cousin, Roberta, down in the Ozarks, and I love to call and talk to her about all the things we did together as kids with our grandmother. I also have a friend in an assisted living facility, and many refugee families who like when I stay in touch.

Following tragedies, many people yearn for redemptive actions. The Mothers Against Drunk Drivers are an example of this. I have some friends whose son died suddenly in his 30s. At first, they were so grief-stricken that all they could see was darkness. But over time, they came up with a project. The son worked with disabled people, so the parents decided to build a bench and a ramp in our beautiful Holmes Park so that people in wheelchairs could enjoy the sunset across the lake, the view of our capital, and the expansive sky vista.

4. Our first decades are spent learning to love and attach to others, while our last decades involve learning to detach.

When my dad returned from the Korean War, he and my mother weren’t getting along. For reasons that weren’t entirely clear to me, he took me and one of my brothers to live in a trailer near his family in the Ozarks. My mother and youngest brother stayed in Colorado. All I remember is the darkness of that trailer. I spent a year, at age six, in hibernation until I was reunited with my mother. When I was reunited with her in a car in Kansas, she was bathed in golden light. The light changed when I was once again with my mother.

As a girl, I was a heat-seeking mammal. I made myself useful and likable, and eventually I found people who liked me. I had a wonderful grandmother who loved me into existence. I remember the first time I realized how much she cared about me. We showed up at her house, and I always ran for the cookie jar, asking her, “What kind of cookies did you make?” And she said, “I made molasses cookies.” And I’d go, “My favorite kind.” She said, “I know, Mary. That’s why I made them.” She called me “My Mary” or “Bright Eyes,” and we would do dishes together. We would work very slowly because we so enjoyed visiting with each other.

“To be happy, we must accept impermanence and adapt to the passage of time.”

I built a life of relationships: aunts, cousins, brothers, friends, children, and grandchildren. The first half of my life, or maybe even the first six decades, involved creating loving attachments. But the second part has become about letting go. My grandchildren are growing up, my daughter and her family moved from Nebraska to Canada, and many of my friends are moving or changing in ways that don’t allow us to be so close. COVID was a crash course in letting go. To be happy, we must accept impermanence and adapt to the passage of time.

There’s a wonderful story about learning to let go. The Buddha and his followers were sitting under a tree in a meadow when a farmer ran up, pulling his hair and crying in desperation. He said, “I have lost my cows. Have you seen them?” The Buddha and his followers looked at each other, and finally they all shook their heads. They had not seen the cows. The man ran away grieving. The Buddha turned to his followers and said, “Aren’t we lucky that we have no cows?”

Our ultimate goal is to find the love we need within our own hearts. That way, as we approach the end of our lives, no matter what is happening, we will find ourselves walking in light.

5. Every moment contains the possibility for bliss.

Βliss can happen anywhere, anytime. To a certain extent, we can orchestrate bliss. We can go to beautiful places, wonderful concerts, an art gallery, or be with people we love. But it also happens magically—if we are ready. It gets easier as one ages. I have a friend named Paul who told me that when he was young, to experience bliss, he needed to be on top of a mountain, or having some incredible experience. Now, he said, “I can go out in my garden, see a caterpillar, and experience bliss.”

The last moment I remember experiencing bliss was during the pandemic. Jim and I hadn’t seen anyone for a very long time, and spring came. It was time to drive out and see our beautiful sandhill cranes that come through Nebraska in March. It was a cold day. We took sandwiches and drove toward the Platte River, about 80 miles away.

As we approached the river, we stopped to have our picnic. We’d been seeing cranes in the fields and hearing their cry—a cry that sounds like something you heard before you were born. But as we sat at the river, eating, the sun going down, I was watching a field beside our car. Somehow, a crane that was landing turned in such a way that it caught the light and became filled with rainbow light. I called it a “cranebow.” It was gone almost the moment I noticed it, but I will hold it in my memory for the rest of my life.

To listen to the audio version read by author Mary Pipher, download the Next Big Idea App today: