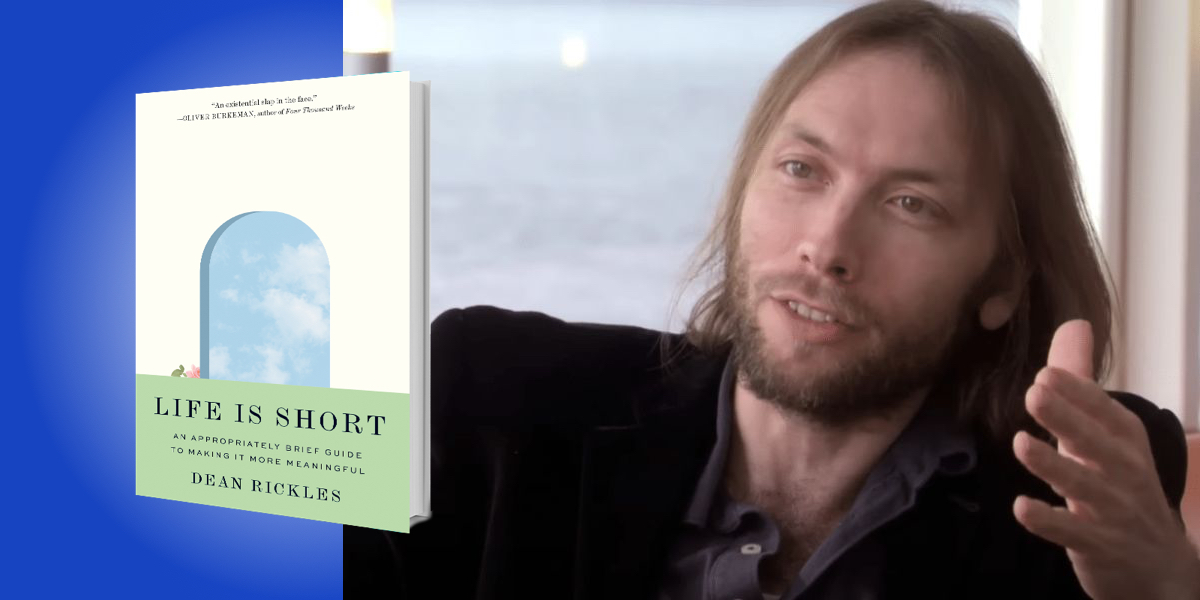

Dean Rickles is a professor of history and philosophy of modern physics at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Below, Dean shares 5 key insights from his new book, Life Is Short: An Appropriately Brief Guide to Making It More Meaningful. Listen to the audio version—read by Dean himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Immortality is not a good idea if you want a life of meaning.

The idea behind Life is Short can best be summed up as a kind of modern re-imagining of the Roman Stoic philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca’s book On the Shortness of Life. Seneca’s main point in his book was that life is not so much short as badly wasted. Since Seneca’s book was written around the start of the first millennium, it is crucial to expand his book using new ideas from philosophy, as well as physics and psychology, that have emerged since his time.

While Seneca argued that “it’s not that we have a short time to live, but that we waste a lot of it,” I argue that life’s very shortness is in fact the primary source of its meaning. Life is short, and it is so for good reason. The German philosopher Martin Heidegger defended a similar view in his book Being and Time, which is undoubtedly a work of genius, but a rather friendlier version of the idea appears in the TV Series The Good Place (where the “good place” is the eternal afterlife.) In the penultimate episode of this show, the inhabitants are offered a way out of eternity and into nothingness, which many gladly accept because of the emptiness of existence without limits.

It is not so much the tedium of eternity that to be concerned with. There is a need for limitations as a way of constraining our possibilities and choices. Death is the most important limitation of all because this finite boundary is required to enable the choosing of possibilities, making only some actual, along with the discarding or sacrificing of possibilities that we have left behind with our choices, which will never become actual. It is this feature that allows us to build meaning into our lives, because we are, in this way, making ourselves as we wish to be. Life, through our choices, becomes a kind of construction project. With no constraints, we never have to sacrifice anything; we never have to choose: we can sample all things, eventually. That boundlessness, while seemingly Godlike and attractive, is ultimately empty.

2. We tend to be careless with our time, despite its very real brevity.

The aforementioned finiteness means that time is a scarce resource for us; it becomes irrational to misuse it, much as it is irrational to misuse other finite resources, such as the Earth’s forests and waters. For this reason, it’s very useful to think of this wastage as a disease of time, just as there are diseases of the body. The idea of wasting time implies that you possess a resource that is being used up now in such a way that depletes it without benefit. It takes from more profitable usage that would lead to your flourishing. Related to this is the idea of discounting the future, so that the farther into the future something is, the less it matters to you. This includes your own future self.

“The idea of wasting time implies that you possess a resource that is being used up now in such a way that depletes it without benefit.”

A nice example of this temporal myopia can be found in an episode of Seinfeld (from “The Glasses” episode) in which he speaks of “The Night Guy”. Night guy is the version of Seinfeld who likes to stay up late, leaving poor Morning Guy to wake up groggy and exhausted. “Night Guy always screws Morning Guy and there’s nothing Morning Guy can do. The only thing Morning Guy can do is to try and oversleep often enough so that Day Guy loses his job and Night Guy has no money to go out anymore.” Of course, Morning, Day, and Night Guy are one and the same guy. But most of us tend to live as if we are split across time into different people in the same way. This causes us to do damage to ourselves in the future, including not caring about the environment which our self in the future will occupy.

If this is a disease, there must surely exist a cure, right? Indeed, there is: it is the ability to think of your future self as still very-much you. It is a mistake to even think in terms of future and past selves: there is just you in the future and in the past. Anything damaging to your self in the future, is damaging you, not a distinct future self. By increasing the vividness with which one views your self in the future, and increasing the feeling of connectedness, you will be less prone to temporal diseases. You would be less likely to over-indulge in alcohol if it gives you an instantaneous, non-deferred headache. If you learn how to think of self as a single thing existing at different time, viewing your self in the future as much the same as your self now, you will try, with practice, to avoid giving yourself in the future a hangover.

3. We waste our life by not engaging with it.

There are various ways to waste time. One is by following frivolous or unworthy pursuits and damaging your self now and in the future. But a far less obvious, equally damaging way is by not really engaging with anything at all in a real sense, but merely existing rather than living. The psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung called this “the provisional life.” Seneca refers to the state as a “tossing about” rather than a “journey,” which forges a path through the space of possibilities. Life is not merely existing. It is not just being there through the lapse of time. It is often thought to be quite rational to stay uncommitted to some particular possibility (be it a job or a relationship).

We have folk wisdom telling us to not put all of our eggs in one basket. With so many options open, though, the result is more like a dreamlike state than wakefulness and reality. We should rather aim for lucid waking: for being active in as many selections from the range of possibilities as we can and for being aware of the choices that present themselves to us. The keeping open of one’s options might seem smart, akin to shrewd management of a financial portfolio, but it simply removes one from actuality and one stagnates, living in what is essentially a primordial void.

“To limit oneself means precisely to kill off possible futures, and so it is a momentous act to decide to do this.”

The provisional life can in fact be understood in rational terms, but it’s still something to be avoided because it is not life. We shouldn’t be quite so dismissive of the avoidance of commitment. The world is indeed full of possibilities. But a world full of possibility is also full of uncertainty. From this uncertainty then comes the anxiety of having to face the risking of decisions. What is the ultimate source of this anxiety? It is perhaps the latent knowledge that each decisive action taken is simultaneously a kind of death; as much a destructive act as a creative or productive one, killing off alternatives to allow just a single one to live.

A commitment is thus a sacrificial offering of sorts, of the other possibilities. The anxiety is the recognition that decisions can matter in a fundamental way, both for the decider and for the world around them. Hence, the solution, assumed to be rational, is simply to not make any decisions and keep all options on the table. Of course, since our space of possibilities is ever-shrinking as we age, we want to retain as many options as possible, viewing them as the very spring of life. But a life without limit can produce only a stagnant pond.

Those that live as if unlimited are referred to in psychology as Puer Aeterni—eternal children. They try to stay unlimited. Unbounded. Godlike. To limit oneself means precisely to kill off possible futures, and so it is a momentous act to decide to do this. One must take responsibility for such active choices (hence the childlike nature of those who refuse to do so.) Failing to take control of the process though does not prevent the elimination and carving of possibilities for you. The only thing that changes is that others will decide on your future possibilities instead. Terrence McKenna’s idea of “radical freedom,” suggests that you should view it as your birthright to take control of your body, mind, and self. If we ignore that this was told to McKenna by a talking mushroom, the following statement is a good one: “You must have a plan. If you don’t, you will become part of somebody else’s plan.”

4. Limits can give birth to freedom.

While we take away the godlike property of being unlimited/unbounded, we leave open the door to another godlike ability. This is the cosmic power of choice; of actualizing some possibility from the many available. Ordinarily, we think of limitations (especially that ultimate limit, death) as things that disrupt our freedom precisely because they remove possibilities in this way. Paradoxically, limit can be seen to give birth to freedom. Furthermore, the freedom born of limitation is where a bounty of meaning lies for all of us. Death is the most important limitation of all because this is exactly what is behind the coherence of choosing possibilities. Death is our greatest gift in terms of meaningful existence since it is the very source of choice, of having to decide, precisely due to its focusing/narrowing effect. Decision is you being in control of what happens. It is you happening to the world, rather than it happening to you. You play a role in forging how things go and in picking who you are. This is real freedom.

“The freedom born of limitation is where a bounty of meaning lies for all of us.”

Such limits become most directly observed at a moment of crisis. There are times which we fully realize we stand at a fork in the road, or we feel on the edge of a cliff. That feeling is fear, because we know at such moments we are pruning some possibilities away in an irreversible fashion. The fear is rational because it is a momentous thing. Often this comes at mid-life, of course, because we know that we are also at a turning point in life: at best, halfway to the end. At this point, decisions seem to take on a greater magnitude precisely because our options are becoming more limited. Indeed, the very word “crisis” comes from the Greek word for deciding: krinein. Here, death, like a beam of light, focuses as it narrows, and it frees as it limits

Taken further, in committing to some course of action you direct the universe as much as your own future. This is nothing short of demiurgic. It is cosmic freedom. Most people instinctively realize this power to affect the world, and yet they cower and become small in the face of so great a responsibility. Instead, they transform into mere objects, and let nature takes its course with them instead. Nature will take its course with you if you let it, guiding your future with its ineluctable logic.

5. Philosophy is the ultimate self-help tool.

Philosophy is relevant to life now more than ever. We live in a world that seemingly wants to dehumanize us at every step, and turn us into mere objects or machines. The kind of deep, open-minded, truth-directed thought involved in philosophy can help you elevate your thoughts despite the lowering effect of happenings on this planet. Ultimately you can elevate yourself so much that you will see ways to help improve things around you and, eventually, generate positive rather than negative feedback.

To listen to the audio version read by author Dean Rickles, download the Next Big Idea App today: