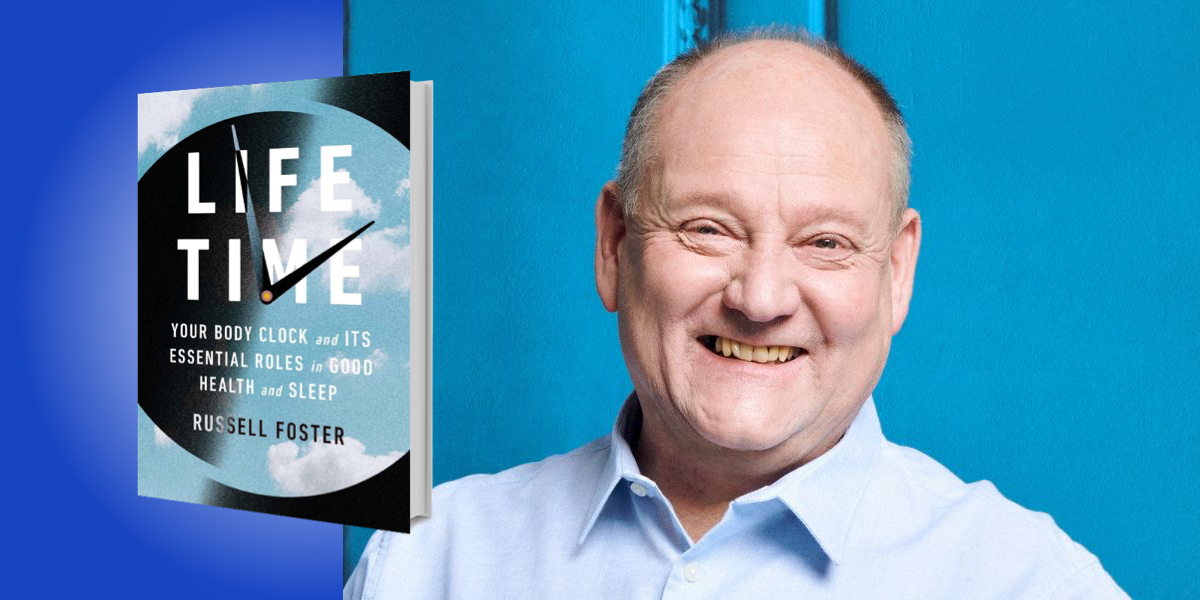

Russel Foster is a professor of Circadian Neuroscience and Director of the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute, at the University of Oxford.

Below, Russell shares 5 key insights from his new book, Life Time: Your Body Clock and Its Essential Roles in Good Health and Sleep. Listen to the audio version —read by Russell himself—below, or in the Next Big Idea App.

1. You can’t adapt to the night shift.

For our bodies to function we need the correct materials, delivered to the right tissues and organs, at the correct concentration, at the optimal time of day. Without this exquisite coordination in time and space—growth, metabolism, memory-formation, decision-making, protection from infection, the repair of damaged tissues, and sleep itself—all fail. Our body clock—circadian rhythms—provides this time structure for life.

The entrenched arrogance of being human means that most of us assume that we are above the grubby world of biology, that we can do what we want, whenever we choose. This assumption underpins the modern 24/7 society, and an economy that is dependent upon night shift workers to stock supermarkets, clean offices, run global financial services, protect us from crime, repair rail and road infrastructure, and care for the sick and injured.

Our full-scale occupation of the night has been possible because of the widespread commercialization of electric light since the 1950s. But this extraordinary and wonderful resource has come with unintended consequences. We have declared war upon the night and thrown away an essential part of our biology: our sleep.

We are governed by a 24-hour biological clock which adapts our entire biology to the different demands of the 24-hour day. The problem is that night shift workers are active when they should be asleep and try to sleep when their biology is prepared to wake. No matter how many years a shift worker spends on permanent night shifts, nearly all (around 97%) night shift workers remain synchronized to daytime. This failure to shift is directly related to light exposure. The daily cycle of light and dark is essential for setting the circadian clock to the 24-hour rotation of the earth. Artificial light is dim compared to environmental light, and after finishing the night shift, an individual will experience bright natural light and the circadian system will still lock onto this brighter light signal as daytime. The biological clock of night shift workers and day shift workers are aligned to day and night in the same way. When at work, night shift workers have to fight an entire physiology telling them to sleep.

“We have declared war upon the night and thrown away an essential part of our biology: our sleep.”

By working against deep biology, night shift workers become vulnerable to a range of illnesses. In the short term, this can include mood fluctuations, pessimism, irritability, impulsivity, lack of empathy, substance abuse, and difficulty concentrating. In the long run, this can develop into disrupted immunity, risk of heart attack, obesity, diabetes, cancer, and mental illness. For instance, a recent study showed that night shift workers during the pandemic were more likely to be admitted to hospital after contracting COVID-19. Other studies have shown that long-term night-shift nurses are more likely to get breast and colorectal cancers. The correlations between night shift work and cancer are considered so strong that shift work is classified as ‘probably carcinogenic [Group 2A]’ by the World Health Organization.

2. What time we take medicine really matters.

Because our biology changes profoundly over the 24-hour day, both the severity of disease and the performance of many medicines show huge variations across the day/night cycle.

Recent studies have shown that there is a 50% increase in the chance of a stroke or heart attack between 6 a.m. and noon, compared to the rest of the day. Drugs used to treat high blood pressure are called antihypertensives, and when these are taken before bedtime rather than in the morning, the risk of stroke or heart attack is halved.

In regards to cancer, when you have your chemotherapy matters as well. For example, when children with leukemia were given anti-cancer drugs in the morning, as opposed to in the evening, the risk of relapse was 4.6 times greater. Another study showed that for women with ovarian cancer who took the same drugs but at different times, survival in one group was 45 percent after five years versus 10 percent survival in the other group. The same drug, the same concentration, but the different times of drug administration produced huge differences in long-term survival.

Vaccination has timing-related effects too. Elderly individuals who were vaccinated against N1H1 flu virus in the morning showed an antibody response three times higher than those vaccinated in the afternoon.

3. When we eat affects metabolic health.

In Europe, there has been a gradual change in eating habits over the centuries. Before about 1100, the main meal of the day was breakfast. During the Middle Ages (1100 to 1500) this shifted to noon. As industrialization proceeded, with the separation of where people worked from where they lived, the main meal of the day shifted to much later. Today, with long commutes and work spanning multiple time zones, the major meal of the day has been pushed to an irregular mid-to-late-evening time slot. This meal timing change has been bad for health.

“There are real links between sleep disruption and mental illness.”

Evening eaters are at a greatly increased risk of Type 2 diabetes and obesity. When individuals were given the same meal in the morning at 8 am and then again 12 hours later at 8 pm, blood glucose levels were 17 percent higher after the evening meal. A detailed study compared individuals who were given the same 20-week reduced calorie diet, but either consumed most of their calories early in the day or late in the day. Those who ate late in the day showed less weight loss compared to individuals who ate early.

4. Mental illness and sleep disruption are linked in the brain.

Regardless of the type of mental illness, whether depression, bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, all of these conditions are strongly associated to sleep and circadian rhythm disruption. In some cases, this can be very severe. These links have been known for a long time, but despite early observations, the cause of sleep disruption has been largely dismissed as an unfortunate side-effect of medication or lack of employment. This is not the case. There are real links between sleep disruption and mental illness.

The first point to make is that the brain circuits involved in mental health overlap with the circuits associated with normal sleep and circadian rhythm generation. Because the pathways in the brain are connected, it is no surprise that sleep disruption occurs in mental illness. A change in a brain circuit that leads to mental illness will also affect sleep.

It gets a bit more complicated because disruption of sleep will disrupt emotional, cognitive, and physiological health—all of which exacerbate a mental illness. Then the mental illness will make sleep even worse. Once started, this positive feedback loop rapidly amplifies poor sleep and poor mental health.

If we reduce sleep disruption, psychiatric symptoms wane. A major Oxford-based trial on nearly 4,000 individuals showed that improving sleep alone produced a highly significant reduction in paranoia and hallucinations. Excitingly, these findings demonstrate that the treatment of sleep disruption in mental illness provides a powerful therapeutic target for symptom reduction.

5. Our sleep patterns are all different and “one size does not fit all.”

Advice about sleep is frequently dramatized and oversimplified: You must get eight hours of sleep, or Waking up in the middle of the night is bad. Rather than widespread enjoyment of sleep, it has become a common cause of anxiety in today’s society—often made worse by inaccurate metrics delivered by sleep apps.

“There are ways to create your own, individual optimum sleep strategy, and it starts by understanding circadian rhythms.”

Individual sleep patterns can be likened to shoe size: one size does not fit all. Prescribing universal sleeping habits is both foolish and potentially harmful. Depending on who you are, the normal range for sleep in adults is between six to eleven hours per night. Also, waking up in the middle of the night is normal for many and is nothing to worry about. Failure to recognize individual variation in sleep is why advice in the media can be deeply unhelpful.

Figure out what works for you. Start by identifying if you get enough sleep. The answer is probably no if you feel that you are not operating at peak performance during the day, or if you are dependent on an alarm clock to get you out of bed. Further evidence includes over-sleeping on free days, taking a long time to wake up, prolonged lethargy, irritability, the need to take afternoon naps, difficulty concentrating, caffeine and sugar cravings, and a heightened sense of worry, anxiety, mood swings, or depression.

There are ways to create your own, individual optimum sleep strategy, and it starts by understanding circadian rhythms. Value and attend to your sleep and biological rhythms to live healthier, more creatively, make better decisions, gain more from the company of others, and view the world with a greater sense of curiosity and wonder. The foolish and the wise all die in the end, but the circadian-and-sleep-wise will be happier, healthier, and very possibly live longer.

To listen to the audio version read by author Russell Foster, download the Next Big Idea App today: