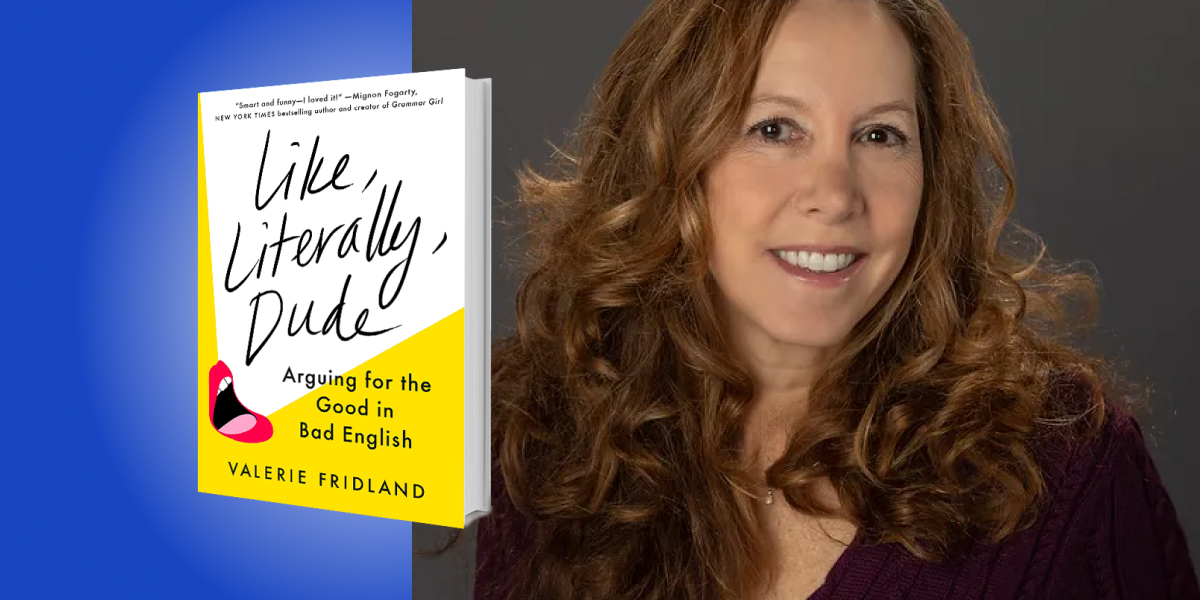

Dr. Valerie Fridland is a professor of linguistics at the University of Nevada, where she was formerly the Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of English. She has spent years researching the way language shapes and is shaped by who we are. Her writing has been featured in Psychology Today and she has appeared as a language expert on media outlets, such as CBS News and NPR.

Below, Valerie shares 5 key insights from her new book, Like, Literally, Dude: Arguing for the Good in Bad English. Listen to the audio version—read by Valerie herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. There is more than one way to look at language.

Most of us can recall a time when we heard somebody say something we find annoying. Maybe it’s hearing literally used non-literally or the omnipresent “dude” and “like” that populate teenage talk. But what if everything you’ve learned about what language should be is based on one very narrow and surprisingly recent perspective?

Prescriptivism is the idea that particular features of language are correct while others are not. This thinking has characterized English since about the 18th century when the loosening of strict class boundaries and the rise of the middle class made language one of the last discerning markers of aristocracy. This coincided with an intense focus on the standardization of English, mainly by members of the upper class who used their own norms and beliefs about what was “good” and “bad” in the process. But as someone who has learned to look at language as a linguist (focusing on the science and history behind the way we talk), I am less interested in what we have come to believe about language and am more interested in what we know about language.

For example, many of us believe there are five vowels in English. In fact, I bet you are reciting them in your head right now: A, E, I O, U, and sometimes Y. But, if we can get what we were taught in school out of our heads, we will see that English has more vowels than this. Say beat, bit, bait, bet, bat, bought, bout, boat, but, boy, bite, book, and boot. The only difference among those words is the vowel sound they contain, meaning that English must have well over five vowels. But written English, which does rely on five letters that represent the multiplicity of vowel sounds, has misled us.

Indeed, a lot of what we think of as language rules are actually social preferences we’ve developed based on written language forms. If we consider a perspective based on linguistic science, we will see that speakers who bring new forms and fashions into English are not breaking any true cognitive or articulatory rules. They are following the tide of linguistic evolution.

2. Language evolution doesn’t happen in a vacuum.

Language evolution requires the help of serious social influencers, but the movers and shakers of the linguistic world are probably not who you would expect. Language evolves because social forces—be it invasions, migration, cultural shifts, or the social soup that is middle and high school—act as triggers in taking underlying linguistic tendencies and giving them social meaning. When we look at research on who instigates new features of speech, we find that the same groups throughout history have usually been at the helm of linguistic innovation: the young, the female, and the lower classes.

“Linguistic leaders are particularly cued in to the value of language in crafting and navigating social identity.”

For example, the Early Modern English shift from verb forms like hath and doth to today’s has and does was more prevalent in letters written by those with lower social status and women, likely because they tended to be more informal and intimate. In one of the first empirical studies of its kind, linguist Louis Gauchat found that young speakers, especially young female speakers, were instigating changes in the French dialect spoken in a small Swiss village in 1905. More recently, when linguists looked at the restructuring of expressions of necessity, which involved a change-up from dusty old must to our more modern have or have got to, guess who led the way? The young, the female, and the so-called “vulgar” classes.

Even though the progression of such changes is largely subconscious, these linguistic leaders are particularly cued in to the value of language in crafting and navigating social identity.

3. There have been major plot twists along the way to modern language.

Sometimes language has done a complete 360 and we hardly realized it. For example, how do you pronounce the -ing ending on progressive participles? Are you a fan of walking and talking or of walkin’ and talkin’? Most people would say that the ‘correct’ speech is -ing rather than –in’, but if you look at the history of this verb ending we find that, in Old English, the progressive participle was formed not with -ing, but with -ind. Because of sound changes occurring a bit later in English, this -ind ending became easily confused with a co-existing -ing ending used to make verbal nouns, leaving us handy modern words like evening and blessing.

“It wasn’t until the 19th century that we start seeing in’ noted in texts with an apostrophe, suggesting that at this point it was viewed as a vernacular feature.”

So, using an -in’ ending on our progressive verb is not sloppy English, but the original verbal ending. And we have decent evidence that, up until the 19th century, “good” speakers did not pronounce that “g” either—in fact, in the 18th century, writer Jonathan Swift (a bit of a grammar maven) wrote that lernen, not learning, was the proper pronunciation, as used at court by the upper echelons of society. It wasn’t until the 19th century that we start seeing in’ noted in texts with an apostrophe, suggesting that at this point it was viewed as a vernacular feature. So, the next time you judge someone for their -ing, you might want to think twice.

4. Sometimes “bad” features can do really good things.

Consider those little ums and uhs that pop into your speech when you hesitate. Surely, those can’t be helpful. After all, we pay speaking coaches good money to help us keep them at bay. But what if research suggests that those filled pauses are unexpectedly helpful to both speakers and listeners?

For one, they seem to help us with speech planning. They occur most often when we are doing hefty cognitive tasks. For example, before we say abstract, difficult, or less common words or when we’ve just started constructing the syntax of an impressively long sentence.

“Sticking a filled pause before a word or phrase seems to act as a cognitive flag to a listener that they are going to need to ramp up their brain to integrate new information.”

Filled pauses also seem to play a communicative role as they signal to a listener that there will be an upcoming speech delay. Even more fascinating is that they seem to communicate exactly how long a delay a listener should expect, with research showing that um precedes longer delays than uh.

Sticking a filled pause before a word or phrase seems to act as a cognitive flag to a listener that they are going to need to ramp up their brain to integrate new information. For instance, when hearing an uh before the name of an item that had not been mentioned before, listeners were quicker at selecting that object on a screen. As an added bonus, other research showed that listeners had better recall of words previously mentioned in an experiment when those words had followed a filled pause when initially said.

So, better communication, quicker processing, and a boost in memory? All from a little pause? Not too shabby for something we think of as bad speech.

5. Language change is fundamental to who we are.

A lot of people scoff at the idea that the changes we hear in speech are positive developments, but do you really believe that Beowulf represented the apex of English? I doubt it, but if we use language change as our measure of decline, then modern English certainly has a lot of explaining to do.

We’ve moved from being a language of incredible complexity—with case, class, gender, and number markings on pretty much every word imaginable—to one where we hardly bother. But are we any less expressive or creative? We’ve invented air travel, internet, and life-saving vaccines all without the help of the complicated morpho-syntax that once defined our language. Instead of pointing to society’s downfall, the speech habits we love to hate today are part and parcel of how language has worked and evolved through centuries. I think we’ve turned out pretty OK.

To listen to the audio version read by author Valerie Fridland, download the Next Big Idea App today: