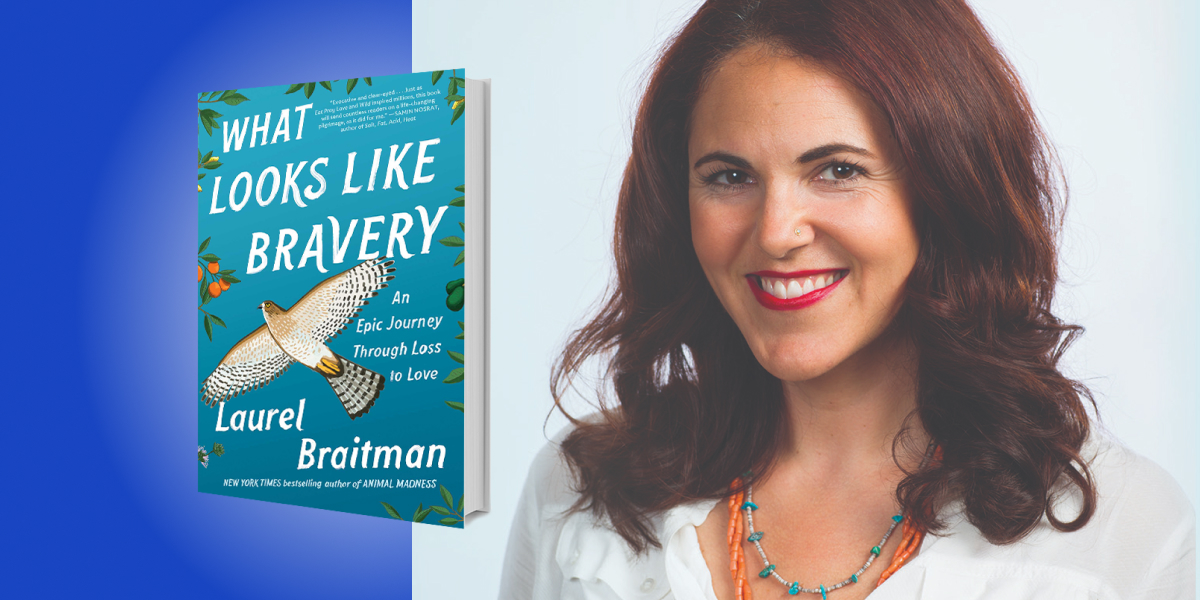

Dr. Laurel Braitman is a New York Times bestselling author with a Ph.D. from MIT in the history and anthropology of science. She is the Director of the Writing and Storytelling Program at the Stanford University School of Medicine. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, Wired, and a variety of other publications.

Below, Laurel shares 5 key insights from her new book, What Looks Like Bravery: An Epic Journey from Loss to Love. Listen to the audio version—read by Laurel herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Without fear, you can’t be brave.

For most of my life I believed that if I was afraid of something, then I was weak or not being courageous. So I hurled myself at all kinds of things that seemed like they’d challenge me—from studying grizzly bears in remote Alaska, to travelling alone through the Amazon basin for months, all before I was old enough to drink.

I chased excellence too—a bestselling book, multiple TED talks, a PhD from MIT, a marriage I thought I was supposed to want. I used success and achievement like an analgesic on the kinds of feelings I didn’t want to admit I had: regret, guilt, shame, especially about how I’d acted when my dad died the year I turned 17.

Only it didn’t work. Those negative feelings just got stronger and eventually, the pain of them broke through. It took me becoming a volunteer working with grieving kids to learn the truth: what scared me most wasn’t what looked like bravery to other people, it was feeling my own difficult feelings that I’d been avoiding since childhood.

“I used success and achievement like an analgesic on the kinds of feelings I didn’t want to admit I had.”

I spent lots of time learning from wise kids and teenagers who, like me, faced profound losses at a young age. I then went on a journey to uncover the wisdom that would lead me to peace. Along the way, I found an excellent therapist named Judy who taught me that bravery is not the opposite of fear. Feeling scared is what allows us to act with courage. Your fears are simply invitations to become the person you were meant to be.

2. Guilt is only helpful once.

I was on the edge of the Bering Sea in Alaska, reporting a story on bald eagles that behave badly (stealing people’s cell phones, swooping down on their dogs, or tearing into groceries at the local Safeway) when I met a wonderful birder named Suzi. She is also a Buddhist and she said something to me I’ll never forget: “Guilt is only really helpful once, in the exact moment where it tells you, ‘Oh, I really shouldn’t have done that.’ As soon as you’ve had that thought, the guilt should go away because it’s not useful anymore.”

This is especially true when it comes to loss—of a person, place, relationship, job, you-name-it. Feeling responsible for something terrible gives us a false sense that if we had only done something differently, then we could have prevented the bad thing from happening in the first place.

We often choose this feeling over confronting what is actually true: that terrible things can happen for no reason at all. We blame ourselves because it makes the world a more logical place. But if you let yourself admit that your guilt is most likely a form of grief and only useful once, then eventually there will be room inside of you for something else. Authentic happiness can come with understanding that the world can be senselessly brutal and disappointing, but it is also full of love.

3. Meaning, not pleasure, is the key to a good life.

Do you feel like your waking hours are meaningful? Do your days, even when they are hard and not paying you what you might want or deserve, feel worthwhile? Do they fill your cup even partly? This is where the good stuff of life is. It doesn’t always feel good—you may not feel “well” or “happy”—because we are human. Can you be your full self at home and at work at least part of the time? Can you enjoy the blessings you do have? Do you spend your time doing things that feel in line with your core beliefs? Will you be proud of yourself when you die? Have you, or are you, improving the world—even in the very smallest way? Do you hold the door open for others?

“Do your days, even when they are hard and not paying you what you might want or deserve, feel worthwhile?”

Too often, we chase pleasure instead of meaning and then become disappointed when pleasure doesn’t lead to lasting contentment. As one of my heroes, Bruce Lee, once said, “Don’t pray for an easy life, pray for the strength to endure a difficult one.” If you make meaning your goal, not happiness or not pleasure, then your life may not be easy, but it will be worth it.

4. Grief is a sixth sense.

Ask anyone who’s ever lost someone and they’ll tell you that grief is not something that we survive, move through, or overcome. It is not progressive and is not something to be avoided at all costs. Instead, it is something that once you feel, you feel forever, right alongside everything else.

It has the capacity to make you more, not less. Grief is love that can sometimes manifest as shame, pain, sorrow, desire, fear, and regret. But it is also proof of our capacity to feel and it is an amplifier of feeling. In fact, grief is a magnifier of joy, awe, and wonder. Without allowing yourself to feel the depths, the highest highs are muted. The pain of loss is a forge that makes the best people because it encourages us to focus on what matters most.

5. The answer is you.

I’m not a religious person. In fact, I’m training to be a secular hospital chaplain. But I do believe in forces that are bigger than us as individuals. You can call this God or grace or mother nature or the human spirit, but whatever you call it, when something rough happens we tend to ask “Why me?” or “Where is God (or grace or a grand plan) in this?”

When my mom was diagnosed with stage four pancreatic cancer, after I’d already lost my dad to cancer, and our home to wildfire, and so much more, that’s what I asked too. But then I heard a story from a chaplain with the Maine Warden Service named Kate Braestrup. A little girl had fallen through the ice of a frozen pond and drowned. One of the Maine wardens, a fellow named Frank, pulled her out. Then he asked Braestrup how it could possibly be that this tragedy was part of God’s plan. Braestrup was a widow herself, her husband was killed in a car crash leaving her with their four young kids. She considered Frank’s question and then said that when her kids asked her why their dad had died, she told them it was an accident. Frank shouldn’t look for God in the girl’s death, she said. Frank had taken the girl out from under the ice with his own hands. He’d tried to resuscitate her even when it was futile and then he’d gone home to his own young daughters, to hug them tighter, his heart broken for the mother whose daughter would never come home again. Frank, Braestrup said, was where God was in this.

“Grace too, whether or not I wanted to admit it, was also in me.”

For me and my family, grace wasn’t in my mom’s diagnosis. It was in my brother who was working as a firefighter paramedic through the pandemic and then coming home to his own ill mom, our friends bringing deli trays, combing through research to identify potentially useful Phase III trials or making custom playlists for us to listen to on our long drives to medical appointments. It was in my students sending heartfelt notes or buying scarves my mom could wear to cover her thinning hair. For us, grace was in the Accessories department, in my pinging text streams, and in the Tupperware containers stacking up in the fridge. Grace was in the clinicians who were taking my calls and the receptionists I was badgering for appointments. Grace too, whether or not I wanted to admit it, was also in me.

We may never get satisfactory answers to the “Why me?” or “Why us?” questions when we fall into something difficult. But religious or not, we can appreciate how the world will almost always reach up to catch us.

To listen to the audio version read by author Laurel Braitman, download the Next Big Idea App today: