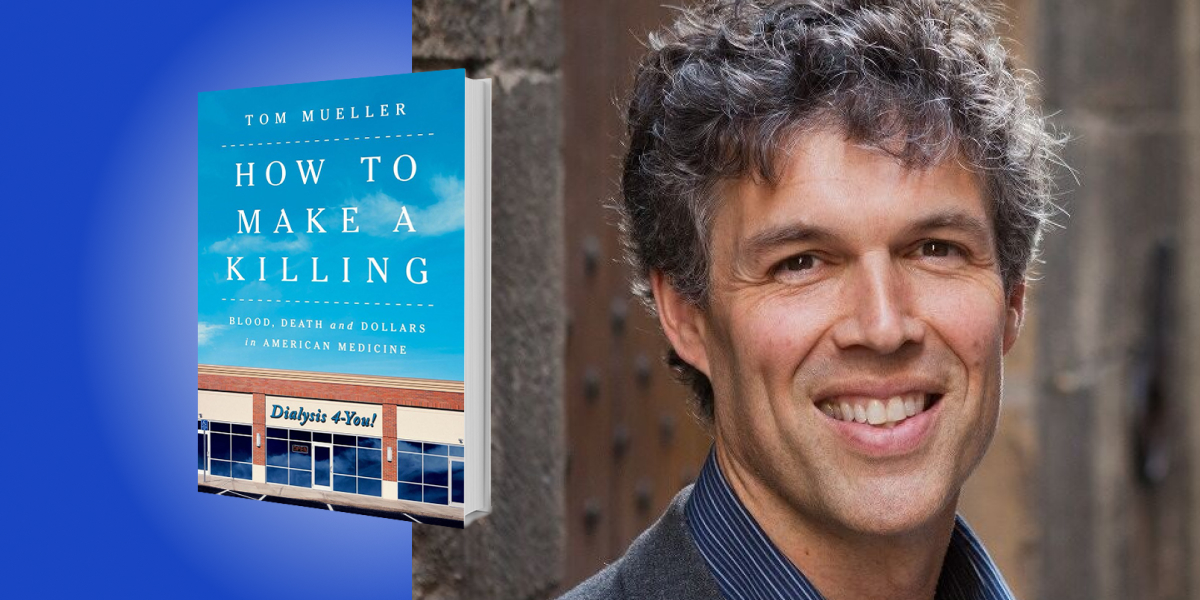

Tom Mueller is a New York Times bestselling author. He studied his DPhil at the University of Oxford and his BA at Harvard University. He is a freelance writer of non-fiction and fiction and has had articles published in the New Yorker, National Geographic Magazine, New York Times Magazine, and Atlantic Monthly.

Below, Tom shares five key insights from his new book, How to Make a Killing: Blood, Death and Dollars in American Medicine. Listen to the audio version—read by Tom himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. A medical miracle has become a healthcare nightmare.

Three hundred and seventy-five million years ago, when the first lobe-finned fish hauled itself up onto dry land, it carried a pool of primordial ocean within itself. It was a puddle of the saltwatery world where its forebears had swum for eons. As this beast morphed into the incredible wealth of terrestrial life we know today—geckos, platypuses, peregrine falcons, hippos, and eventually humans—all of its ancestors continued to carry that same ancestral ocean inside of them. We can all thank our kidneys, the organ that maintains the precise chemical solution that our cells, blood, and tissues need to survive. The kidneys are the guardians of homeostasis, that delicate balance of salt water, electrolytes, and assorted nutrients.

Some ancient civilizations sensed this near mystical wizardry; the Egyptian Book of the Dead sings the kidneys’ praises. Embalmers sometimes even left the kidneys in place when they mummified their pharaohs, perhaps thinking that these obscure organs played some vital role in the pharaonic afterlife. The Hebrews saw the kidneys as the source of profound intuitions and desires, as well as a repository of divine wisdom: “My kidneys give me counsel in the night,” says the Psalmist.

Today, though, kidneys don’t receive a lot of respect. We praise people for their heart, their brains, their lungs, even their guts, but spare not a word for their renal fortitude. Yet without those fist-sized, bean-shaped organs flanking the base of our spine, all the other organs, even our mighty brain, would swiftly fail. “Superficially, it might be said that the function of the kidneys is to make urine,” wrote Homer Smith, a groundbreaking physiologist, “but in a more considered view, one can say that the kidneys make the stuff of philosophy itself.”

The fact is, your kidneys are essential to your survival. Until the 1960s, kidney failure was a death sentence without reprieve. Then a series of medical innovators, engineers, and tinkerers devised the first dialysis machines, sometimes using sewing machine motors, ice cream makers, sausage casings, and parts from downed Luftwaffe fighter planes. Suddenly people who had been condemned to death could live for years, even decades.

The trouble was, limited dialysis centers meant that only a handful of the thousands of kidney failure patients could be treated; the rest died. One center instituted a so-called “God panel,” to determine who would live and who would die. These heart-wrenching decisions helped trigger the birth of a new field: bioethics. Major news outlets picked up the story, and Congress began to see kidney failure as a threat to the American dream, and dialysis as the antidote.

In 1972, Richard Nixon signed a law making dialysis the first ever Medicare for All medical condition: the U.S. government agreed to pay for the dialysis treatment of nearly all of its citizens. This sounds like a triumph, yet today, dialysis patients in the U.S. have on average the worst outcomes, and spend more on treatment, than in any other developed nation. So, what’s going on?

2. Fast food is hard on the kidneys.

Today in America, there is an epidemic of kidney disease, driven by three underlying epidemics: diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. At the root of all this, of course, is fast food, with its unrelenting bombardment of salt, sugar, and fat.

“Fast food” can also describe a philosophy of healthcare, widely practiced in U.S. dialysis and other medical areas. According to the “fast food” model, standardized, assembly-line medicine will provide the best care at the lowest cost. Fast food medicine grew out of the underlying premises of neoliberalism, which the U.S. has bought into since Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. For-profit, free-market medicine yields optimal, and optimally priced, health outcomes.

“The United States currently ranks 29th among OECD nations in life expectancy and 33rd in infant mortality.”

Sadly, these assumptions have proven disastrously wrong. In healthcare overall, the U.S. provides the worst care at far higher cost than other developed nations. We now spend about 18 percent of our GDP on healthcare, and our medical outcomes have dropped to the bottom of the OECD list by most measures. For example, the United States currently ranks 29th among OECD nations in life expectancy and 33rd in infant mortality.

The assumptions behind fast food medicine have also proven dead wrong in U.S. dialysis. About a quarter of U.S. patients die every year, compared with 9 to 12 percent in Western Europe, and only five to six percent in Japan. Back in 2009, two senior nephrologists, Raymond Hakim, former Chief Medical Officer of Fresenius, and Robert Foley, published a paper in a respected medical journal. Its title was, “Why Is the Mortality of Dialysis Patients in the United States Much Higher than the Rest of the World?” Pretty straightforward message, right? Some foreign nephrologists are less diplomatic. Distinguished Australian nephrologist John Agar recently said to me, “For many years now, I’ve been telling my American colleagues that they have to stop killing their patients.”

3. The limits of free market medicine.

“We thought we were going to find, quite frankly, that the big dialysis chains offered better care at a lower cost,” says economist Ryan McDevitt at Duke, who has researched the industry for over a decade. “Actually, we found the opposite. The big chains chase the dollar no matter what; they favor quantity over quality. The trouble is, in healthcare, the patient outcomes depend so much on the quality of care you get. Death rates go up, hospitalization rates go up, transplant rates fall, and so on. Any measure that could get worse pretty much got worse after the big chains acquired independent facilities.”

McDevitt and fellow economists at Penn State, Brigham Young, the Federal Trade Commission, and elsewhere have identified a phenomenon in American dialysis they call “stealth consolidation.” Big firms gobble up little ones under the radar of the Federal Trade Commission, which has produced the current duopoly of Fresenius and DaVita, who control some 80 percent of the market. They’ve also highlighted another key economic principle: incentives and how profit motives can mold human behavior. We’re talking about what is euphemistically known as “cherry picking” and “lemon dropping,” something that major dialysis companies strenuously disagree with and deny.

“Cherry picking” goes like this: Privately insured dialysis patients are vastly more profitable than Medicare or Medicaid patients, sometimes 10 or more times more profitable. So, private payor patients get the red carpet treatment: the best treatment times, the most attentive service, and so on. If a privately insured patient and a Medicare patient are competing for a dialysis station, it’s easy to imagine who often gets the nod. This is called “cherry picking,” selecting and pampering higher-margin patients, who make you more money.

“Lemon dropping” is the opposite phenomenon: Dialysis patients who are typically low-value Medicare patients, or patients who complain about the quality of care, or particularly ill patients who might lower the healthcare ratings of a dialysis facility, may be involuntarily discharged, or “lemon dropped.” Again, dialysis companies deny that they do this, but reporting suggests otherwise. It also indicates that certain discharged patients are often blackballed by other facilities in their area, even those run by competitors. Their only remaining option to get dialysis is the emergency room, which, as one senior nephrologist told me, is a death sentence of six to twelve months.

“Cherry picking” and “lemon dropping” have been reported in other areas of healthcare, including nursing homes and hospitals. An economist might predict that such behaviors are almost inevitable in aggressive, for-profit medicine, where caregiver behavior, conscious or unconscious, can be shaped by economic incentives.

4. The Musketeers and Real Americans.

At a skit performed at the corporate retreat of a dialysis leader, DaVita, senior executives, dressed as Musketeers, pretend to sword fight and kill three black-masked villains who threaten their firm’s profits. These villains are: a government healthcare official, an insurance executive, and a federal prosecutor. Though clearly meant as a joke, this skit provides insights into the organizational culture of the firm involved. In real life, many major dialysis firms have faced charges of illegal kickbacks, Medicare fraud, patient harm, violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and so on. They have signed enormous legal settlements to resolve these allegations while carefully denying liability.

“In real life, many major dialysis firms have faced charges of illegal kickbacks, Medicare fraud, patient harm, violations of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, and so on.”

Some dialysis leaders galvanize their troops by borrowing organizational methods from religion, sports, and the military; they’ve even compared such organizations to a cult. Daniel Barbir, a dialysis nurse who fled totalitarianism in Romania when he fled to the U.S. in 1982, was horrified by his company leaders performing on stage. “I said to myself, oh my God, I ran away from Communism, and here it is again, I won’t sell my soul for these people. I would rather dig ditches!” These are the voices who really ring out: patients and caregivers caught in a tough place, who nevertheless speak out with courage, clarity, and poignancy that is hard to forget or ignore.

Megallan Handford, a former LAPD officer who retrained as a dialysis nurse, said, “I have to move fast from one patient to another. No time to ask them how they feel, how their family is, just ‘Okay, you’re still breathing,’ and move on. My job is nursing people, but I can’t do my job on this assembly line.” Sherry Thompson lays her hand on the arm of her husband Gerald Thompson, a dialysis patient, and says, “It’s got to stop. We’re going to do what we can to make that happen. That’s our goal. We don’t want anybody to feel this way. We don’t want anybody to go through the abuse.”

5. We CAN do better.

Dialysis is the canary in the coal mine for American healthcare overall.

In 1972, when Congress made kidney failure the first Medicare for All disease, Republicans, Democrats, and most Americans at large assumed covering dialysis was the first step towards comprehensive national health. In fact, starting around this time, many developed nations began making comprehensive healthcare a birthright of their citizens. But America took a very different road. Watergate and Vietnam destroyed the bipartisan momentum toward national health. The economic crisis of the OPEC oil embargo and runaway stagflation refocused the national attention. However, it was refocused, not on building enduring government programs like universal healthcare, but on cutting costs, and handing more and more of our public goods, including our medicine, to for-profit firms.

We need to take a hard look at where that road we started down in 1972 has taken us; to healthcare that is poor yet ruinously expensive, and out of the reach for many Americans. We need to fix dialysis and treat some of our most vulnerable patients with the respect they deserve. Dialysis again needs to become the bellwether and we need to re-align our healthcare system overall with the fundamental tenets of the Hippocratic oath and human compassion. The challenges we face in fixing dialysis, and American healthcare overall, are daunting.

But take heart, or gird your kidneys, countless other countries point the way to better care. Here at home, however, things have gotten so bad that a bipartisan consensus like we had in 1972 may again be possible.

To listen to the audio version read by author Tom Mueller, download the Next Big Idea App today: