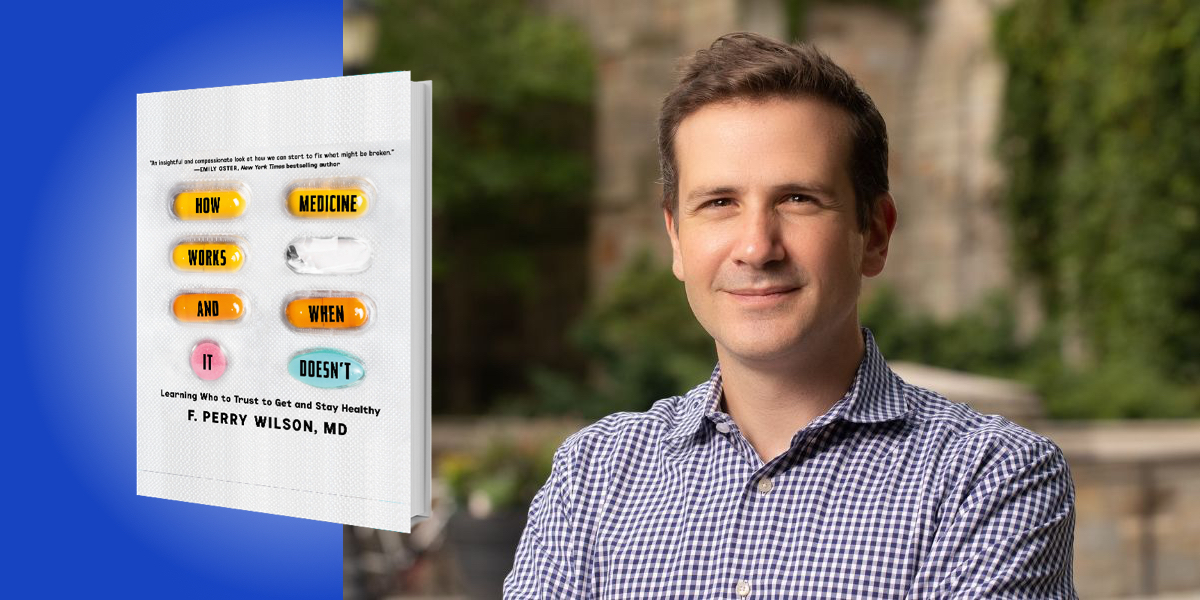

F. Perry Wilson, MD graduated from Harvard College with Honors in Biochemistry. He attended medical school at Columbia College of Physicians and Surgeons, before completing his internship, residency, and fellowship at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2012, he received a master’s degree in Clinical Epidemiology, which has informed his research ever since.

Since 2014, his goal has been to use patient-level data and advanced analytics to personalize medicine to each individual patient. To that end, he holds multiple NIH grants and is the Director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. Dr. Wilson is internationally recognized for his expertise in the design and interpretation of medical studies, and has appeared on CNN, HLN, NPR, Vox.com, and the Huffington Post, among others. His free online course, entitled “Understanding Medical Research: Your Facebook Friend Is Wrong” is one of the most popular courses on Coursera.org.

Below, F. Perry Wilson shares 5 key insights from his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t: Learning Who To Trust to Get and Stay Healthy. Listen to the audio version—read by F. Perry Wilson himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Motivated reasoning leads to terrible medical decisions.

One of the main problems of our internet- and social media connected age is the sheer amount of data we are all exposed to. Our feeds are full of facts and factoids—some true, some overhyped, some outright lies. When exposed to so much data, our human instincts kick in. What data do we believe? The data we want to be true. This is the essence of motivated reasoning, and it happens all the time.

Motivated reasoning explains why two rational, thoughtful adults can look at election results and come to a different conclusion about whether the election was fraudulent or not. It’s why some people believe that the attacks of 9/11 were orchestrated by a nefarious cabal within the U.S. government. Of course, when I mention this to my students, they often say “wait, you mean people want there to be a nefarious cabal within the U.S. government?” And the answer, actually, is yes. Not because they support such a group of people, but because it imposes order in a world that may otherwise seem chaotic. The fact that a few terrorists with box cutters could inflict so much pain and suffering is terrifying—it feels like we can never be safe—but if all these horrible events were actually perpetrated by a government cabal, we can tell ourselves that it won’t happen again, we can feel comfortable in our own lives, because surely the cabal would not strike at us.

In medicine, motivated reasoning makes people make bad choices. We often see this when it comes to topics like vaccination. Although they often have trouble describing it, many people feel like vaccination is “wrong” somehow. It violates some sense of personal autonomy. It hurts (at least for a moment when the needle goes in) someone who is otherwise well. Many people are motivated to find a justification to refuse a vaccine because they are just sort of icked out by it. And of course, the internet is full of people providing anecdotes to justify that belief—friends of friends with horrible reactions—claims, again, of a shadowy government cabal that is trying to reduce the population. And people believe them, not because they are gullible, or lack intelligence, but because they want to.

Recognizing your own motivated reasoning is the first step to making better choices about your health.

2. “One simple thing” medicine almost never works.

Turn on your TV late at night and you’ll be bombarded by ads for what I call “one simple thing” medicine. Lose weight and stubborn belly fat with this one, simple supplement! Increase your memory with this one simple exercise! Become a better parent with this one simple trick to get your kids to behave!

“Unless you are already in the peak of health, becoming truly healthy requires change.”

Many of us roll our eyes at these ads. The low production values clue us in that something isn’t right, and we flip to a more interesting channel. But “one simple thing” medicine is everywhere. In fact, the whole “wellness” industry is a collection of one simple thing ideas; certain lifestyle brands often combine multiple “one simple things” to improve every aspect of your life—all of which are available for a low monthly subscription.

Even pharmaceutical companies try to sell you on this. Want to reduce your risk of heart attack? The one simple thing you can do is take our cholesterol-lowering drug!

We all want quick fixes, and people selling you something know that. We like fixes that require minimal change in our own lives—because change is difficult. But the truth is, unless you are already in the peak of health, becoming truly healthy requires change. There is no one thing that will make you live longer, be healthier, have more energy. It’s lots of things. It’s change.

So be skeptical whenever anyone—whether on TV at 3am, or in the medical clinic—suggests your ills will be fixed by one little pill. Change takes work.

3. The most powerful tool in medical research is the coin flip.

Quick question: I present you with 1,000 people who take cholesterol medication and 1,000 people who don’t take cholesterol medication—who is more likely to have a heart attack over the next decade? What’s your answer?

It’s actually a bit of a trick question—the people on cholesterol medication are almost certainly more likely to have a heart attack. This is because the characteristics of people who take cholesterol medications—older, higher cholesterol levels, prior heart disease—are fundamentally different from the characteristics of people who don’t take cholesterol medications (like my three children, for example).

“Randomized trials are the pinnacle of medical research, and one of the simplest ways to know which studies you can ignore and which you should pay more attention to.”

What that means is that observational medical research—observing who takes what drug or does what exercise or eats what food, and then linking that to some outcome like heart attack or death—is fraught with problems. One of the ways I teach this to my students is to point out that people with a high foie gras intake live way longer than people who don’t eat foie gras. Of course, it’s not the fatty duck liver making them healthier, it’s the fact that they are rich and, at least in this country, more money generally means better access to health care as well as dramatically lower social stressors.

Medical research has solved this observational data problem with something called the randomized trial. Take a group of people who don’t eat foie gras and, at random—with a coin flip or its computer equivalent—assign half of them to eat foie gras (provided by the study sponsor), and watch what happens. Considering how many calories are in foie gras, I expect the foie gras group might do a bit worse this time!

Randomized trials are the pinnacle of medical research, and one of the simplest ways to know which studies you can ignore and which you should pay more attention to. A study says drinking red wine is associated with lower rates of cancer. Was it randomized? No? Then ignore it—wait for a randomized trial.

By the way, this is a real example: observational studies of red wine have shown multiple protective effects that randomized trials have not replicated. Why? Well… think about who drinks red wine.

4. Real medical breakthroughs are rare – they are also inevitable.

The news media loves a breakthrough story. In the past month, I’ve seen articles extolling a breakthrough in cancer treatment, asthma treatment, Alzheimer’s treatment, and diabetes. At the rate these articles come out, we probably should have eliminated all disease in just about a year and a half. And yet, disease persists. Because real breakthroughs are rare.

My patients, especially those with life-threatening conditions, are desperate for a breakthrough. And I am desperate to find them one. But, realistically, I know that medical science doesn’t really work that way. True game-changing medicines—like the direct-acting-antiviral agents that can cure hepatitis C—arise usually after decades of research.

Take the COVID mRNA vaccines, for instance. They certainly felt like a breakthrough—a totally new vaccine technology that could potentially put an end to the pandemic? Breakthrough! But actually that vaccine technology started to get developed two decades ago, during the SARS pandemic of 2002. We’ve had 20 years to work on those vaccines; we just hadn’t heard about it because it didn’t matter until SARS-CoV-2 came along. And, of course, though the vaccines seemed like a breakthrough when they were first released, the bloom has come off the rose a bit, as long-term efficacy has waned and new variants have learned to evade our immune defenses.

“True game-changing medicines—like the direct-acting-antiviral agents that can cure hepatitis C—arise usually after decades of research.”

Still, breakthroughs are inevitable. They will happen. There will be a cure for cancer—it will just be on the backs of decades of prior research leading to that cure. Miracles aren’t waiting for us out in the woods like in a fairy tale, they are created by us. They take work. But that work is worth it.

5. The most powerful medicine in the world is trust.

As a doctor, I want my patients to make the decisions that are right for them and where they are in their life. I view my role as a guide, someone who can characterize the potential risks and benefits of those decisions, reason through them with my patients, and come to a conclusion. But without a bond of trust, a feeling that you and I are in this fight together, the therapeutic alliance never develops. So how do we build trust?

First, doctors and patients need to realize that we are on the same side. You don’t like the short office visits? We don’t like the short office visits either. You don’t like your insurance company? Believe me, we don’t like your insurance company either. It’s us against the world.

Doctors need to be honest, admitting when they don’t know something, or when the science is uncertain, and patients have to realize that false certainty hurts trust in the long run—because false promises inevitably get broken. Doctors have to stop ignoring the really big problems that harm our patients—things like social isolation—and start being more than prescribing machines. It will take some work but, as I’ve mentioned several times, everything worthwhile takes work.

Medicine isn’t perfect. But no other human project has reduced suffering, pain, and death more than medical science. In other words, look how far we’ve come, and imagine how far we can go.

To listen to the audio version read by author F. Perry Wilson, download the Next Big Idea App today: