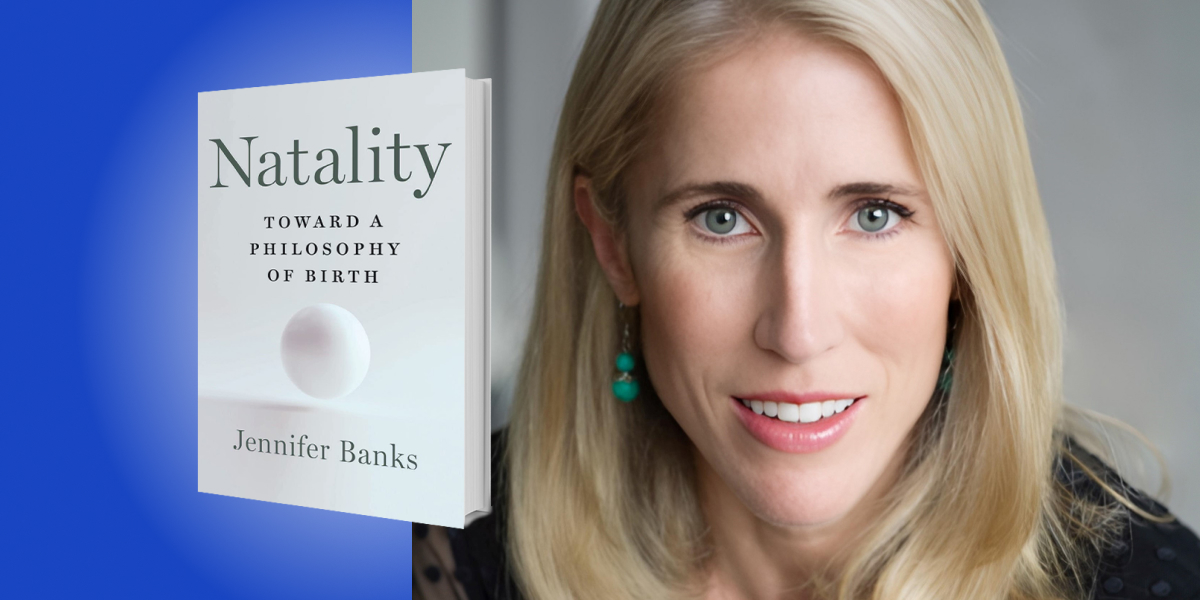

Jennifer Banks is Senior Executive Editor at Yale University Press. Her work has appeared in the Boston Review and Pleiades, among other publications.

Below, Jennifer shares 5 key insights from her new book, Natality: Toward a Philosophy of Birth. Listen to the audio version—read by Jennifer herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Natality, defined.

When my mother told a friend that I planned to title my book on birth Natality, her friend said, “Don’t let her do that! No one will know what she means!” Her friend wasn’t entirely wrong. “Natality” is not a word in our everyday vocabulary, though its counterpart “mortality” very much is. The exploration of natality came from what I saw as a very strange omission in our language, stories, and cultural life. We don’t have a word for birth that conveys what mortality conveys for death: how birth shapes every human life from its beginning to its end.

Growing up, I had the privilege of an excellent education, but birth was not the subject of the undergrad survey classes or graduate seminars I took as a student. So in 2009, when I gave birth to my first child, I was left asking the questions that so many people ask after giving birth: why did no one tell me what this was like? Why did no one prepare me? My life had just been revolutionized by birth. These absences and silences in my education and upbringing stunned me.

Around this time, I also observed a strange thing: death had become a cottage industry. The bestseller lists were full of books on death. At Yale, undergrads lined up to take a philosophy class called Death, one of the most popular classes on campus. Across the globe, aging baby boomers gathered with hip millennials in death cafes to discuss their mortality while sipping craft beers and eating cupcakes decorated with tombstones.

But there were no birth cafes, no hipsters lining up to frequent them. In experiencing birth and trying to understand those experiences, I was beginning to consciously wrestle with my natality, and this led me into blue sky, unexplored territory. Although this wrestling was initiated by my experiences giving birth, anyone can engage with natality. We all, of course, were born.

2. Always be beginning.

Birth is about beginnings—the beginnings of our individual lives and our children’s lives, but also the beginnings of our collective lives as communities and as a species. To the degree that we are unprepared for birth, we are unprepared to begin new things at all—to be creative, to come up with new solutions to old problems, or to deal with people or realities we’ve never experienced before.

The political theorist Hannah Arendt coined the phrase “natality.” She is perhaps a surprising person to have insisted on birth’s beginnings, as the defining experience of her adult life was not becoming a mother (she never had children), but her near escape from Nazi Germany’s death camps. Arendt was a German Jew. After Hitler came to power, she was arrested by the Nazis and later interned at a camp for women in the south of France. She escaped that camp and fled to New York where she was given a second chance at life. She took that chance and made the most of it, becoming one of the leading public intellectuals of the post-war period. Her new beginning did not entail forgetting what had just happened.

“Birth for Arendt was the great anti-totalitarian act.”

Arendt began writing to try to process the utter collapse of the world she had known. In 1951, she published The Origins of Totalitarianism, a book that opens by stressing the “grimness of the present” and by describing a calm in which hope had died. After hundreds of pages of analysis of genocidal regimes, she ends her book with a stunning passage about birth’s beginnings. She concludes soberly but with a cautious sense of resilient promise that “every end in history also contains a new beginning. This beginning,” she continues, “is the promise, the only ‘message’ which the end can ever produce.” She argues that beginning is our “supreme capacity” as humans and that it is identical with our freedom. We are each guaranteed this free capacity to act and begin new things, not by any government but simply by virtue of our having been born. Birth for Arendt was the great anti-totalitarian act.

Her work reminds us that both our individual lives and our civilizational futures depend on our natality—our ability, willingness, and responsibility to act as agents in our societies and to engage with the work of constantly renewing our world.

3. Shocked wonder at the miracle of being.

Most people I know who have had a child testify to what I experienced at the birth of my children: a shocked sense of wonder. In the place where there had been no person, there was suddenly a new, unprecedented being—a person who arrived with her own features, moods, aversions, and affinities. Where had she come from? Who was she? Who would she become?

Across the globe, people birth around 385,000 babies a day, and those births are not treated as breaking news by the media. Birth can seem so ordinary and routine that it is easy to forget how each of those babies represents a completely new expression of what a human life can be. In the 21st century, in a capitalist age of ruthless exploitation of people, other species, and our planet, life is often treated as cheap and disposable. In such conditions, expressing a sense of wonder at the miracle of life can seem a little out of touch. Cynicism or despair are often seen as more realistic responses to our world.

“Birth can seem so ordinary and routine that it is easy to forget how each of those babies represents a completely new expression of what a human life can be.”

But feeling and expressing wonder is not a denial of reality; it is a natural engagement with reality, as Hannah Arendt and so many other brilliant thinkers recognized. By staying close to birth, we can witness how each of us is, as Hannah Arendt put it, an “infinite improbability which occurs regularly.” This infinite improbability, Arendt argued, “constitutes the very texture of everything we call real. Our whole existence,” she continued, “rests… on a chain of miracles.”

As far as we know, life does not exist on any other planet. Its coming into being was a cosmic fluke, as was the evolution of our species. Our wonder testifies to the very strangeness, fragility, and uniqueness of this rare thing we are inside of: life itself. For Hannah Arendt and many other figures, a “shocked wonder at the miracle of being” was a defiant refusal of totalitarian nihilism, fatalism, false narratives, and oblivion.

4. Birth is other people.

“Hell is other people.” This famous line from French existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit entered the zeitgeist decades ago and its sentiment infuses our contemporary moment. The news this week, for instance, has been full of stories of Americans shooting innocent people who made the dangerous mistake of turning into a neighbor’s driveway or knocking on their door. Amid the intense polarization of a highly armed citizenry, other people can quickly become a threat to one’s safety, autonomy, or well-being. So much of our public discourse reinforces the idea that a person is better off going it alone, conserving her own resources, and doubting the motivations of her peers.

The truth, however, is that we live among other people in webs of profound interconnection and indebtedness. The separate, autonomous selves we have come to maniacally believe in are largely illusions. Birth reminds us of these interconnections. While we can die alone, we are never born alone. Most births originate in an intimate encounter, however pleasurable or painful, between two people. Most babies live for months in another person’s body, depending entirely upon that body, and most deliveries are assisted by nurses, doctors, midwives, neighbors, friends, or family members. To keep a newborn alive requires around-the-clock care; if we survived our infancy and childhood, it was because other people made sacrifices and took care of us, however imperfectly. We owe our lives to them.

“We live among other people in webs of profound interconnection and indebtedness.”

These interconnections between people are what the deadliest, most genocidal political regimes have wanted to sever, even as they mobilized the masses. Once people are isolated from one another, they have little chance at collective action, and therefore little power to resist false propaganda, dangerous ideologies, and even deadly directives. Engaging with natality has therefore a distinctly democratic function; it reminds us of just how significant and life-changing our coming together with other ordinary people can be.

5. Humanity has a future.

I remember sitting with my father and his brothers at a Christmas party in my mid-twenties and hearing them speak in despairing tones about the state of the world. “I wouldn’t bring children into the world today,” one commented. The others nodded in quick assent. A moralism, a deep concern for their children and future generations, as well as worries about the sustainability of our planet, drove their conversation.

They weren’t alone in their concern; natality rates are now at record lows in much of the industrialized world. For many, it has become hard to believe that the decades and centuries that stretch out before us will be livable for humans or that future generations will have the chance we have had—to be alive or maybe even to live healthier, happier, more enlightened, or more prosperous lives than our ancestors.

But giving up on our future is a dangerous proposition too. What motivation would we then have to care for the world or make it a better place? As the great American novelist Toni Morrison observed, the brightest and most confident accounts of a redemptive human future have come in recent decades not from such centers of power, but from their margins, from the people most vulnerable to catastrophe. Listening to the voices on those margins, Morrison concluded that “Time does have a future. Longer than its past and infinitely more hospitable—to the human race.”

She was right. Reading through her illuminating and challenging testament to natality, I thought a lot about my father. His experience of becoming a grandfather in his sixties changed him. It opened up a future he had despaired wasn’t imaginable. When my daughter, his first grandchild, was born, he held her in his arms, looked down upon her with bewildered awe, and said, “She is just beginning.”

To listen to the audio version read by author Jennifer Banks, download the Next Big Idea App today: