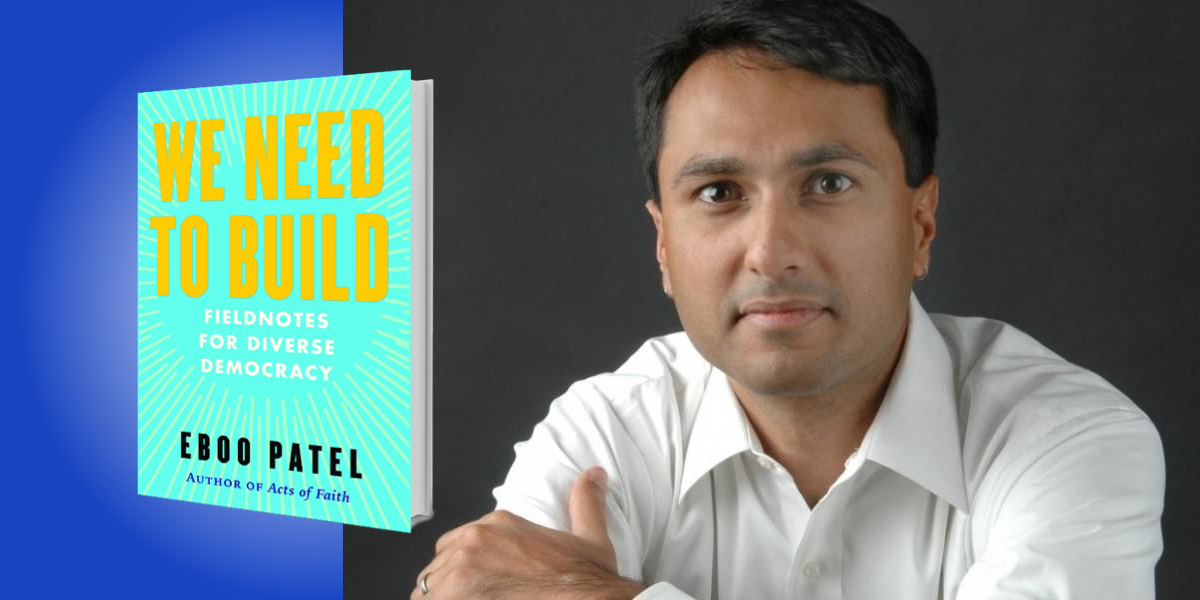

Named “one of America’s best leaders” by U.S. News and World Report, Eboo Patel is Founder and President of Interfaith America, the leading interfaith organization in the United States. Under his leadership, Interfaith America has worked with governments, universities, private companies, and civic organizations to make faith a bridge of cooperation rather than a barrier of division. Eboo served on President Obama’s Inaugural Faith Council, and holds a doctorate in the sociology of religion from Oxford University, where he studied on a Rhodes scholarship.

Below, Eboo shares 5 key insights from his new book, We Need to Build: Field Notes for Diverse Democracy. Listen to the audio version—read by Eboo himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Evolve like Alexander Hamilton.

In Lin-Manuel Miranda’s iconic telling, the early Hamilton is an all-out revolutionary. He is “young, scrappy, and hungry.” He fans sparks into flames, seeing the ascendancy of his name and the success of the revolution as inextricably linked. He boldly says that he will lay down his life if it sets us free.

The American Revolution of 1776 needed that brash spirit—both to inspire it, and to win a remarkably unlikely victory against a mighty empire. But as the show goes on, Hamilton needs to evolve. His mentor and patron George Washington reminds him that while winning is easy, governing is hard. Hamilton needs to cool his hot head to make alliances, to negotiate and compromise, to build for the long term. He writes more than he fights, builds more than he protests. Instead of throwing rocks at windows, he walks through doors and negotiates at the table in the “room where it happens.”

Revolutions do not go on forever. As the great civil rights leader John Lewis once said, the drama in the streets always ends and gives way to something else. Will that something else be better than the thing that was in place before? The answer to that question has everything to do with the answer to these questions: can those who have raged against the unjust, old order build and run the institutions of a new order? Can we evolve from protestors against a discriminatory regime into architects of a better system?

“The drama in the streets always ends and gives way to something else. Will that something else be better than the thing that was in place before?”

2. The goal of social change is not a more ferocious revolution, but a more beautiful social order.

People are generally wary of turning away from a system that they know, bad as it might be, if they do not believe that something better can be built. In order to trust that something better can be built, people need to have faith in the leaders who are doing the building. Do you have what it takes to be in charge? Being in charge means articulating a vision for what the new system will look like, offering a detailed blueprint of its various institutions, empowering and training up a group of builders, and knowing how to build yourself.

It is harder to organize a fair trial than it is to fire up a crowd, harder to run a successful school than to tell other people that they are doing education all wrong, harder to sustain alternatives to policing that ensure public safety than it is to chant slogans in the street. Yet every decent society needs fair trials, good schools, and public safety. That’s just the beginning of the list of institutions and structures that need to be efficiently erected and effectively run in a large-scale, diverse democracy. In short, we need to defeat the things we do not love by building the things we do.

3. America is not a melting pot, but a potluck.

The metaphor of America as a melting pot is over a century old—and is ripe to be replaced. I think we should start thinking of America as a potluck nation. Potlucks are civic spaces that both embody and celebrate pluralism. They rely on the contributions of a diverse community; if people don’t bring an offering, the potluck doesn’t exist, and if everyone brings the same thing, the potluck is boring. And what a nightmare it would be if you brought your best dish to a potluck, and you were met at the door with a giant machine that melted it into the same bland goo as everybody else’s best dish. The whole point of a potluck is the diversity of dishes.

“What a nightmare it would be if you brought your best dish to a potluck, and you were met at the door with a giant machine that melted it into the same bland goo as everybody else’s best dish.”

Potlucks respect diverse identities by enthusiastically welcoming the gifts of the people who gather. They facilitate relationships between people by creating a space for eating and socializing and surprise connections. They cultivate in people the importance of not just the individual parts and the connections between them, but also the health of the whole. Everybody benefits from a clean kitchen, enough dishes and silverware, and a safe and open place to eat and socialize. When it comes to a potluck, these are the structures of the common good. Everybody plays a role in their upkeep.

4. We are no longer a Judeo-Christian nation; we are Interfaith America.

Religion is the single largest contributor to American civil society, and the engine of social change movements from abolition to civil rights. It is the dimension of diversity that the 1776 generation of European-American founders came closest to getting right. We are a stronger country when faith is fully embraced as a source of inspiration and a bridge of cooperation. When it comes to religion, we are on the cusp of a paradigm shift away from the Judeo-Christian and toward interfaith America.

The phrase “Judeo-Christian” was a concrete social response to the anti-Catholicism and antisemitism of the early 20th century. It was a civic invention of the 1930s, and it did good work for almost a century. It was for sure better to be a Jew or a Catholic in America in 1990 rather than 1930. But we have changed as a nation. There are now almost as many Muslims in America as there are Methodists, twice as many Buddhists as Episcopalians, and the median age of Hindus is 20 years younger than the median age of Lutherans. Moreover, atheists, agnostics, and spiritual seekers are approaching a third of our total population.

“We are a stronger country when faith is fully embraced as a source of inspiration and a bridge of cooperation.”

It is time for a new chapter in the story of American religious diversity. I lead an organization called Interfaith America, and its mission is to build the nation Interfaith America. We define it as a country that welcomes all of its religious diversity, nurtures positive relationships between different religious communities, and engages them in common action for a common life together.

5. Lead with an outstretched hand, not a raised fist.

If you are in the Ukraine, by all means raise your fist and maybe more against the Russian military invading your nation. But if you are in an American suburb and your neighbor voted differently than you did, offer an outstretched hand. Have a mutually enriching conversation. Seek to learn something about a different point of view. Make an effort to find other things that you agree upon. Diversity is not just the differences you like.

The definition of pluralist civilization, says the great Jesuit philosopher John Courtney Murray, is living and talking together. The person who destroys the conversation, who insists on only his own voice being heard, is called a barbarian. The signal achievement of American democracy is having different identities and divergent ideologies living together in a common civic and political community. This is rare in human history, and it needs to be cherished, protected, and strengthened.

That means being able to disagree with people on some fundamental things, while working with them on other fundamental things. Heart surgeons who have different views in immigration policy operate on patients together. Parents who disagree in abortion coach little league together. This is the heart of our civilization. Bridges don’t fall from the sky or rise from the ground—people build them. And these bridges are a requirement in a pluralist civilization.

To listen to the audio version read by author Eboo Patel, download the Next Big Idea App today: