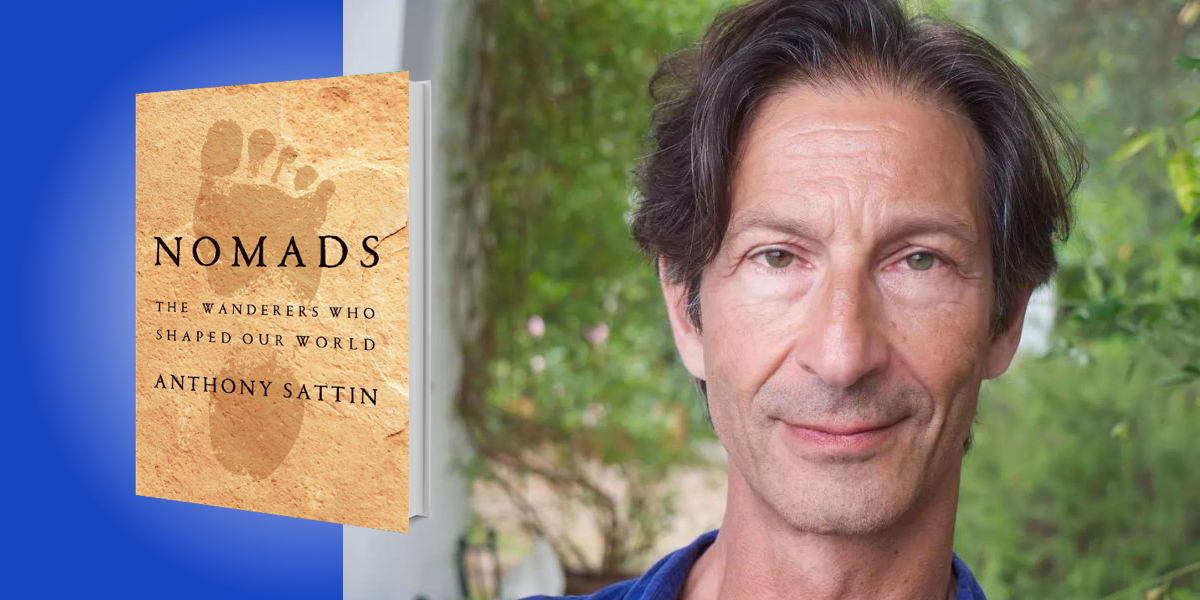

Anthony Sattin is journalist, broadcaster and contributing editor to Condé Nast Traveller, editorial advisor on Geographical Magazine and a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

Below, Anthony shares 5 key insights from his new book, Nomads: The Wanderers Who Shaped Our World. Listen to the audio version—read by Anthony himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Humans have lived on the move for most of history.

Until more or less 12,000 years ago, we all lived on the move as hunters or gatherers. Around 9500 BC, something extraordinary happened. At a place called Gobekli Tepe in southern Turkey, near the Syrian border, a group of people who lived on the move began to build what seems to have been the first stone monument, cutting pillars 10 or 12 feet high out of the limestone bedrock. They moved and decorated them, and then raised them into a circle on a hillside, with two taller pillars in the center.

Seven thousand years before the pyramids or Stonehenge, this was perhaps the beginning of humans reshaping the world around them—and it was achieved by people who lived on the move. It also seems to have been the catalyst that led to the domestication of crops and then animals, thus the creation of villages that turned into towns and cities. This is not the traditional view of how humans settled, but it seems that this process began as a result of mobile people wanting—or needing—to build a sacred site.

2. Histories preserved by written word only tell half of the story of humans.

A prominent Oxford historian once described history as a path picked through ruins. It is an image that begins with the first stone monument at Gobekli Tepe and conjures up the great ancient civilizations of Egypt, Greece and Rome, of Incas and Mayas, the glories of Renaissance Europe, the Chicago and New York skyline, and all the rest. This is a settled view of history, however, and it is one that relegates nomads—who don’t build permanent structures, or preserve their stories in writing—to the role of destroyers of monuments. It can also leave them out completely.

“This is not the traditional view of how humans settled, but it seems that this process began as a result of mobile people wanting—or needing—to build a sacred site.”

For instance, our histories tell us about the glories of ancient Rome and of Han China. This is the period from roughly 200 BC to 200 AD. However, across the 4,500 miles between the eastern frontier of the Roman Empire and the Great Wall of China lay a vast, linked-up confederation of nomad tribes who may have constituted a mighty nomad empire. We know them as the Scythians, Sakas, Xiongnu, Hun, and other names. They usually get no more than a brief mention in written histories. Even when they are included, it is to explain how the great Persian emperor Cyrus lost his life, or the reason behind the building of the Great Wall. As always, the story is more interesting and more complicated.

3. The great nomad empires were about more than murder.

The nomads who are in our histories—most commonly Attila the Hun, Genghis Khan and Timur, or Tamberlaine—are usually presented as killers. It is true that much blood was spilled, but we don’t often hear about the wonderful things that came out of these nomad-dominated times.

The empires of Genghis Khan and Timur, during 1200 AD and 1300 AD, were the largest the world had known. They stretched from China across Central Asia to Persia and the Middle East. The laws that governed these empires were harsh. However, at a time when much of the rest of the world was fractured and divisive, this huge central part of Eurasia enjoyed the benefits of a Mongol peace. That peace was built on strong central authority, low trade tariffs, open borders, and a network of posthouses where you could get a fresh horse or bed-and-board for the night. With the right permit, you could even sleep in silk sheets. There was also freedom of conscience alongside freedom of movement. Out of this openness came the glories of the Silk Roads. Out of this Mongol flourishing came the European Renaissance, the voyages of discovery, the Age of Reason and the creation of the world as we know it.

4. Settled people have always had a problem understanding nomads.

Benjamin Franklin was a man of exceptional brilliance, a Founding Father of the United States and signatory of the American Declaration of Independence. He could not, however, understand why settlers, who had once sampled what he called “the wandering life,” could never come home. This applied to woman as much as men. When a settler was bought or brought out of “captivity” among Native Americans, they were welcomed back into the community. In some cases, they received help in the form of a gift of land or a house. Invariably and before long though, they would head back out to the wilderness.

“The native elders understood the drawbacks of a settled education.”

On the other hand, when Franklin and the people of Philadelphia offered to pay to educate Native American children in the settlement, sharing the benefits of arts and sciences, the Iroquois elders refused. They explained that when their children returned to camp after this education, they would be good for nothing. The native elders understood the drawbacks of a settled education.

The flip side of that incomprehension—usually accompanied by suspicion, mistrust, even fear—is a sort of nostalgia for an earlier and what often seems a simpler way of living. It sits behind the writings of Greek and Roman philosophers, who dreamed of arcadia, just as it does in the writings of people such as Thoreau, and more recently, Bruce Chatwin.

5. Settled people need nomads.

Settled people have always needed nomads, just as nomads have always needed the settled. For the past 12,000 years, since humans first began domesticating crops and animals and building monuments, the settled and mobile have lived in mutual dependence. Now more than ever, we settled people need nomads.

“Nomads have remained constant in their understanding of their dependence on the forces that govern the natural world.”

Whether you believe the climate emergency is a hoax or a real and existential threat, there is no denying that our relationship with the natural world is out of kilter. Nomads have remained constant in their understanding of their dependence on the forces that govern the natural world. Just as our climate is changing, it would seem like a good moment to consider how nomads behave towards the natural world.

It is also a good moment to consider some of the benefits nomads seem to enjoy; living lighter, living in a roaming community based on mutual support, bound together by a shared lifestyle but also by shared traditions and legends forged around campfires, committed to the cupped hands of memory. Perhaps most important in our troubled times, nomads seem to be more flexible in their thinking. Their world requires them to have a range of solutions for every problem. As our settled lives becomes ever-more troubled, this presents a perfect moment to see the world through nomadic eyes.

To listen to the audio version read by author Anthony Sattin, download the Next Big Idea App today: