Cass R. Sunstein, Robert Walmsley University Professor at Harvard Law School, was Administrator of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in the Obama administration. He was the recipient of the 2018 Holberg Prize, and is the author of The Cost-Benefit Revolution, How Change Happens, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness (with Richard H. Thaler), and other books.

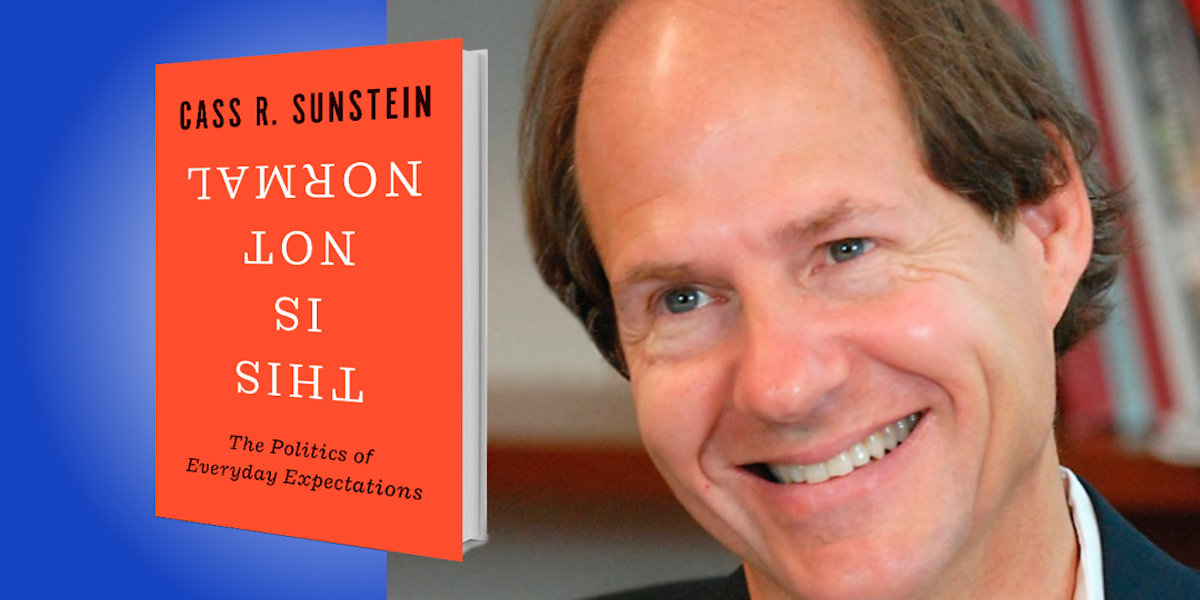

Below, Cass shares 5 key insights from his new book, This Is Not Normal: The Politics of Everyday Expectations (available now from Amazon). Download the Next Big Idea App to listen to the audio version—read by Cass himself—and enjoy Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Our judgments are based on what we see as normal, and that shifts.

If we are in a room with a lot of faces that are really mean and angry, we might see a face that is only kind of mean and angry as being gentle and nice—even though it’s still a mean face. If we are surrounded by unethical behavior, where people are cheating a fair bit, we might think that cheating a little bit, a slight bending of the rules, is completely fine. If we are surrounded by corruption—not just cheating, but actual corruption—we might think that if a police officer says to us, “I’d like a little bribe in order not to give you a ticket or a penalty,” then that’s completely fine. Similarly, if we are surrounded by the most severe forms of discrimination on the basis of sex and race, the most hateful forms, then we might think that less-hateful forms are completely legitimate, or at least not that horrible.

This phenomenon is both a challenge and an opportunity; it suggests that if things get better, if corruption diminishes, we will start to see things as bad that we formerly took for granted. It also suggests that if things start to get worse, if we start to be surrounded by horrific misconduct, we might start to see things we’d formerly disapproved of as pretty much okay, because they’re not horrific. The power of the “normal” means that our ethical judgments are often based on what we see around us.

2. Authoritarianism comes on little cat feet.

Authoritarianism develops in increments. Even when Hitler rose to power in Germany, things happened really slowly—it was like a movie that was unfolding in slow motion. Yet in retrospect, it seems that it happened very fast (and at some periods in the 1930s, it did). But in general, authoritarianism moves by stealth, until it gets to the point where some people think, how did our nation turn entirely around? It happened by increments.

“Our ethical judgments are often based on what we see around us.”

3. Lapidation is a social practice—it’s all around us, and it’s really bad.

“Lapidation” is an old word, which I’m currently trying to give a new purpose to. It’s a word for stoning. The idea is if someone engages in a transgression—let’s say they deny a truth, or they act in a way that’s morally questionable—they sometimes get stoned. And misconduct, if it’s genuinely horrific, does deserve some sort of response. But if someone says something that is inconsistent with current norms—maybe they’re left of center, maybe they’re right of center, maybe they are out of touch with emerging trends, maybe they are dissenters because they are confused or because in some sense, they’re right—sometimes people like that get lapidated. That means that there is a mob of people who are throwing things at them. Those things are hard and painful.

For the person who engaged in the misconduct, it can often ruin a week, a month, a year, and in the worst cases, a career. A good response comes from Shakespeare who said, “The quality of mercy is not strained.” A better response came from Jesus who said, “He who is without sin, let him cast the first stone.” Let’s not, I suggest, cast the first stone.

4. The best forms of radicalism today come from about a century ago.

Alice Paul was a great feminist who was one of the principal people behind the right of women to vote. She was committed to the equal dignity of human beings, a simple idea with radical potential—radical in the best sense. It suggests that in a free country, no one is given less respect than anyone else by virtue of some characteristic, such as the color of their skin, age, gender, or whether their legs work. The commitment to the equal dignity of human beings has unrealized radical potential. It is consistent with free markets—it might be even built into the idea of free markets.

“The difference between the science fiction author and the historian is less crisp than it might seem.”

The twin idea I’m suggesting is improbably technocratic, and associated with Walter Lippmann, a contemporary of Alice Paul. Put simply, it’s “please get the facts straight.” If the question is whether a pandemic is real, whether a vaccine works, whether climate change is dangerous, or whether a food is unsafe, give pride of place to people who have actually studied this and have relevant expertise. This radical idea has transformed cultures all over the world, extending and often saving lives. To cast contempt and doubt on people who have devoted their lives to studying, for example, the human heart or what gives rise to cancer, is to cut out the foundations from what makes human society at its best even possible. We need a commitment to equal dignity and a commitment to getting the facts right.

5. Clio, the goddess of history, is a trickster.

Nothing is foreordained in history’s arc. Small things and serendipitous things—acts of courage and acts of cowardice—often turn cities, cultures, nations, and even planets around. We often think that where we are is inevitable, but it isn’t. Many times, it is a product of small acts of bravery and insistence by individuals, many of whom never make it into the history books.

Historians who track the twists and turns of the arc that I’m describing are often alert to this point, and are stunned to see how something small made a big difference. Authors of science fiction, who engage in counterfactual history, ask things like: What if the South won the Civil War? What if Hitler decided he would be an artist? What if Donald Trump decided he really liked business better than politics? The difference between the science fiction author and the historian is less crisp than it might seem. To be sure, they’re different, but in many respects, they are playing the same game.

To listen to the audio version read by Cass Sunstein, and browse through hundreds of other Book Bites from leading writers and thinkers, download the Next Big Idea App today: