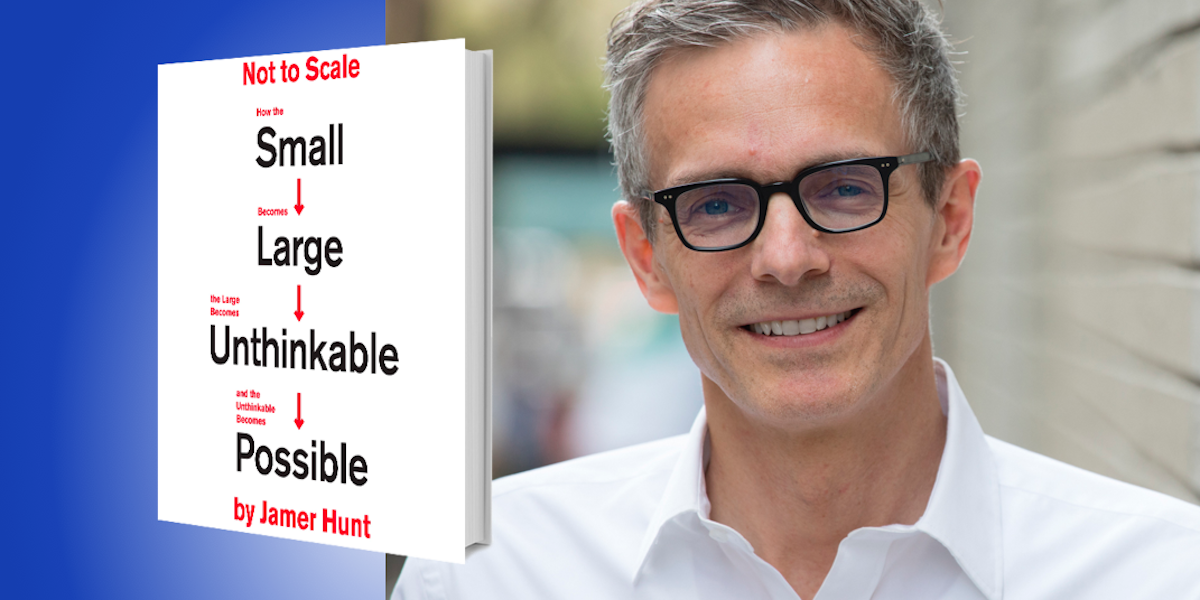

Jamer Hunt is the Vice Provost for Transdisciplinary Initiatives at The New School, and was founding director of the graduate program of Transdisciplinary Design at Parsons School of Design. He co-founded DesignPhiladelphia, the country’s largest design week, and has published over two dozen articles for platforms such as Huffington Post. He was also included in Fast Company’s list of the “Most Creative People.”

Below, Jamer shares 5 key insights from his new book, Not to Scale: How the Small Becomes Large, the Large Becomes Unthinkable, and the Unthinkable Becomes Possible. Download the Next Big Idea App to enjoy more audio “Book Bites,” plus Ideas of the Day, ad-free podcast episodes, and more.

1. Scale organizes experience.

When you get up in the morning and get dressed for work, do you wear a sweater, a light jacket, or a heavy coat? Chances are you check a thermometer to decide. A thermometer gives quantitative specificity to the temperature outside—it takes a subjective experience, and makes it common to all of us. Scale is a way to measure how big, small, fast, heavy, cold, or full something might be. In other words, scale organizes experience, and makes it knowable.

2. We are not to scale.

My laptop keeps increasing in storage capacity, but it also keeps getting slimmer in size. I keep my whole life on that computer; almost everything that I’ve ever made, recorded, built, or designed is all stored in a medium that I have little perceptual access to. We spend over half our days staring at content on screens we can look at but not touch, smell, taste, or hear. We’ve separated the world from our body and senses; as a result, scale no longer makes sense in the same way.

“You have options because you can shift scale to gain new advantages.”

3. As we shift in scale, the problems change.

A scientist named Frits Went once posed an interesting thought exercise: Can an ant learn to read? You might think of ants as smart or not, but that’s not really the issue. Because as you shrink a book down to the scale of an ant, the bonds between the electrons and the pages are so strong that an ant would not be able to turn the pages. In other words, as you move in scale, the problems change. As another example, notice how Facebook was originally a way for college students to judge one another’s appearance. Then it grew larger and larger in scale, and eventually became weaponized to help tilt an American presidential election.

4. Use scalar framing for a multi-pronged approach to tough problems.

Much like the famous video Powers of Ten, the world looks very different as you zoom in and out. Let’s look at, for example, how we might make bicycling in New York City more popular. At the scale of the individual, a useful goal could be designing a better bicycle, one that folds more easily and is easier to carry around. If we zoom out, we’re now looking at the streetscape, and it becomes an urban design problem: How do we redesign the streetscape to make it safer for bicycling? Zooming out to the national level, how do we use governmental regulations to incentivize bicycle use?

“Act at the scale that maximizes your capacity.”

5. Four insights about scale that drive innovation:

- Every problem is both local and global. Realize that you have options because you can shift scale to gain new advantages.

- Act at the scale that maximizes your capacity. If you’re a lone industrial designer, then go ahead and redesign the bicycle to make it more comfortable, foldable, or easier to carry. But if you’re that same lone individual who also rides bikes on the weekend with a city councilwoman, then perhaps the two of you can change city policy to make bicycling safer or more appealing.

- You will gain insight from framing at another scale. You’ll likely see a whole new set of possibilities.

- At every new scale, new collaborators will emerge. As you shift your scale from the individual to the streetscape, for instance, wouldn’t it be enlightening to talk to a city bus driver, or a traffic engineer, or a crossing guard? These collaborators will have new ways of looking at the problem that you never imagined.

For more Book Bites, download the Next Big Idea App today: