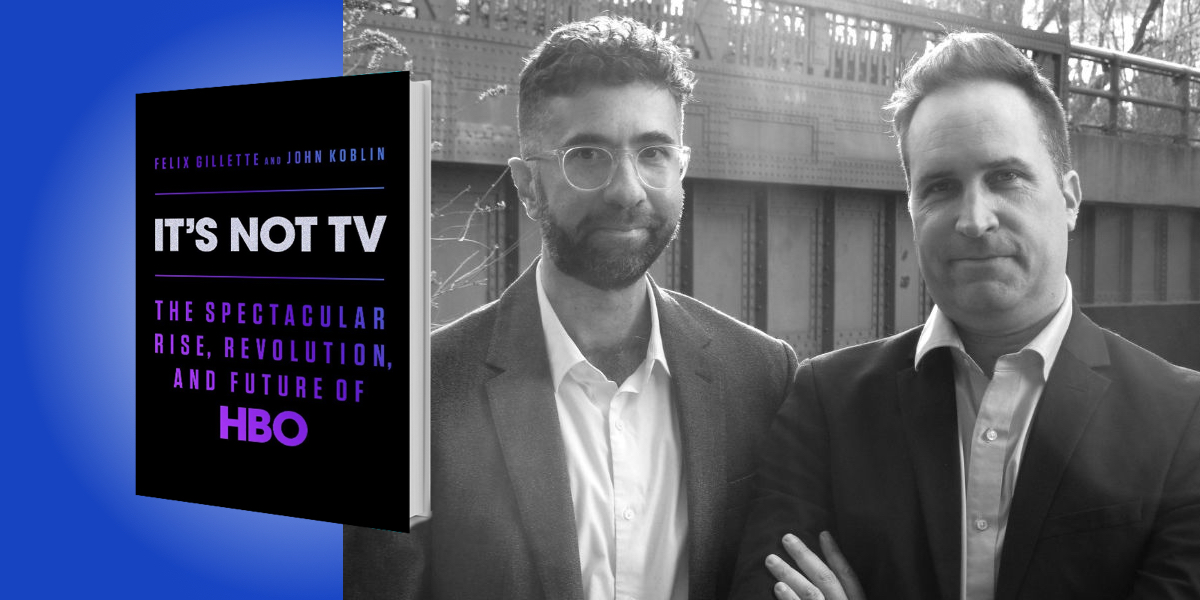

Felix Gillette is the enterprise editor for Bloomberg News’s media, entertainment, and telecom team, as well as a features writer for Bloomberg Businessweek. John Koblin is a media reporter for the New York Times, covering the television industry.

Below, Felix and John shares 5 key insights from their new book, It’s Not TV: The Spectacular Rise, Revolution, and Future of HBO. Listen to the audio version—read by Felix and John—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Counterprogram, counterprogram, counterprogram.

From its very inception in the early 1970s, HBO executives came to believe that if HBO was to thrive in the long run, it would have to focus on doing things differently than the big three commercial TV networks, ABC, CBS, and NBC. The broadcasters were too well entrenched, too strong, and too rich to compete with head on. Their control over popular culture felt unassailable. HBO would have to exploit programming opportunities that the networks were ignoring. Everything HBO did would have to be different. Otherwise why would anybody keep paying over the next 50 years?

HBO would evolve from a small and insignificant speck in the Time, Inc. empire into a juggernaut of popular culture by following one simple rule: counterprogram, counterprogram, counterprogram. HBO stood for the Home Box Office, and during its early years, the network counterprogram by putting on the air any kind of programming that home viewers would previously have had to buy a ticket to see. In the real world, that meant Hollywood movies, music concerts, boxing matches, and stand-up comedy performances. At one point, comedian George Carlin went on HBO and performed his classic routine, “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television,” but you could say them on HBO. That was the point.

Eventually, HBO codified its counterprogramming strategy in an advertising motto. In the mid-1990s, HBO tapped the advertising agency BBDO to dream up a new ad motto for the network, and the agency got to work on mockups of potential ads and slogans. An HBO executive in New York named Bridget Potter took a look and wasn’t impressed. The tone of the material was too safe, too conventional to help her make her point. Potter put together a sizzle reel compiling some of the most outlandish, off-color, violent and profane moments from HBO’s recent programming history. Once, during the campaign’s development, a handful of folks from HBO trekked over to BBDO offices. On a screen at the front of the room, the HBO team fired up the reel of clips for everyone to consume while they nibbled on cookies for several minutes.

“The key is not to mimic what everyone else has done successfully, but to find something new and different and distinctive.”

They quietly watched the montage of comedians telling wildly inappropriate jokes, gory scenes from Tales from the Crypt, and shocking footage from various HBO crime documentaries. When it was over, Potter recalls a member of BBDO’s crew broke the silence. “Whatever that is,” he said, “it’s not television.” Exactly. Potter remembers thinking, “Now you get it.” In the months that followed, HBO steered some $60 million into a campaign to blitz the viewing public with its new tagline: It’s not TV. It’s HBO. That would go on to win the first ever Emmy for a TV commercial decades later.

It’s still an invaluable reminder that the key is not to mimic what everyone else has done successfully, but to find something new and different and distinctive. Counterprogram, counterprogram, counterprogram.

2. Listen to the storyteller, not the crowd.

In 1995, HBO decided to invest heavily in episodic television and within a few short years, it would change TV forever, elevating Hollywood’s second tier into a culturally revered art form. David Chase, David Simon, Darren Star, Alan Ball, and Tom Fontana all had found success in network TV, and all of them were deeply frustrated by the guardrails of broadcast television. HBO set them free.

In 1996, each of the four broadcast networks rejected David Chase’s idea of a mob boss who goes into therapy. A top CBS executive said the therapy made him look weak. A Fox executive thought a violent mobster would be a turnoff to advertisers. By the time David Chase met with HBO, in February 1997, he was expecting much the same. It couldn’t have been more different. “Lean harder into the mobster in therapy angle,” they told him, and “go ahead, shoot the show in New Jersey. It’ll be more expensive, but it’ll look real.”

HBO made these decisions not by mining the preferences of their customers. HBO was a wholesaler. They didn’t know much about their viewers. That information belonged to the cable and satellite companies. Instead, HBO relied on the gut instincts and intuition of its programming executives. When HBO executives sent the first episode of The Sopranos to a focus group, it scored horribly. But HBO executives saw it differently. They liked it a lot, and their job, as they saw it, was to enable their stable of auteurs to do what broadcast TV would never permit them to get away with. Between 1997 and 2002, HBO premiered several new TV series, including Six Feet Under, Sex and the City, Oz, The Wire, and of course The Sopranos. That programming point of view would soon change TV forever.

3. Have a point of view.

One way that HBO was able to successfully differentiate itself from the broadcast TV networks was to have a strong point of view. Because they were afraid of alienating a particular swath of viewers, the broadcast TV networks tended to shy away from programming that took a particular stance on any controversial political topic. HBO decided to do things differently.

From its early days, HBO leaders saw the network as a powerful vortex of progressive values. From AIDS to abortion to gun control to global warming, HBO was ever-eager to throw itself into controversial political subjects and to score points on behalf of their liberal beliefs. Having a point of view allowed HBO to pursue creative projects that its competitors simply wouldn’t touch.

In 1992, Bob Cooper, the head of HBO’s Original Films Department, made a call to the prolific TV producer Aaron Spelling, whose past hits included Charlie’s Angels and The Love Boat. A few years earlier, Spelling had signed on with NBC to produce a film adaptation of And the Band Played On, the bestselling book that investigated America’s early inept response to the AIDS crisis. For several years, NBC had sat on the project.

“Their mission, in short, was to create quality noise.”

Spelling had grown frustrated, eventually concluding that a story about gay activists struggling against the indifference of the political and medical establishment was too controversial for NBC, and perhaps for all of network TV. Bob Cooper heard of Spelling’s predicament and reached out with a suggestion: bring it to HBO. The cable network, he told Spelling, wasn’t afraid of stirring up controversy. Months later, when NBC’s option on the film finally expired, Spelling sold it to HBO. And Cooper quickly ushered the film into production.

Because HBO was willing to have a strong point of view, during the casting process, several well-known Hollywood actors, including Richard Gere, Steve Martin, Anjelica Huston, and Lily Tomlin, signed on to play minor roles. To support the cause, the actors arranged to work for reduced salaries, and to donate half of their paychecks to AIDS charities. The making of the movie soon generated several small controversies. A number of prominent activists accused HBO of unfairly blaming the gay community for the spread of AIDS. And several scientists alleged that HBO was twisting the historical record and spreading bad science. But when HBO broadcast And the Band Played On on September 11th, 1993, it was held as a major moment in the struggle for AIDS awareness, and was credited with being the first major movie to confront the AIDS crisis. Critics were impressed.

HBO executives distilled their new movie strategy into a pithy slogan. The network’s goal, they told reporters, was to create movies that felt like cultural events that inspired editorials and provoked outrage. Their mission, in short, was to create quality noise. “The value of quality noise is that we believe it helps give meaning to the word HBO,” Bob Cooper said.

Having a point of view generated a ton of free press for the network. Such controversies moved coverage of HBO beyond the cultural pages of newspapers, and onto the op-ed section and the front page, again and again. Throughout its history, being willing to have a strong point of view got HBO noticed.

4. Advocate for your brand every day.

For decades, Americans had been used to getting their entertainment on television for free. Before TV, those stories were free on the radio. It had always been this way. HBO’s proposition, beginning in 1972, was a novel concept. Pay us for a subscription.

It was a tough sell. At HBO, unlike the free broadcast networks, executives began to believe that they couldn’t take a single day off from advancing their cause. There was no off-season for HBO. If a customer wasn’t satisfied with the network, they could cancel the service just like that. At HBO, executives began to say, “We need to be elected every month.” Top executives soon became advocates for a strategy that they called The Permanent Campaign. The basic idea was that you didn’t wait until the feverish onset of a crisis to figure out who you needed to court and win over to defend you publicly in your moment of need.

It was much more effective to have already invested the time and energy under cooler circumstances in courting those influential members of public opinion. Much better to have already forged a bond. Every lunch, every dinner, every film premiere was an opportunity to sit down with someone of note in public office or the press and start building a foundation of mutual understanding and respect. And whereas most entertainment studios and TV networks courted the Hollywood Trade Press, HBO decided to cultivate relationships with reporters, columnists, and editors in New York and Washington.

“There was no off-season for HBO.”

HBO eventually went as far as to bring some of the key cultural arbiters into the fold. In 2008, Frank Rich, then the influential New York Times columnist, was hired as a consultant. By 2012, he was producer of a new comedy series called Veep, which would win the Emmy for Outstanding Comedy Series four times. In his consulting duties, he found two scripts from a promising British writer in the slush pile. That writer was Jesse Armstrong. Rich and Armstrong became close. When Armstrong told Rich that he had an idea for a show about an aging billionaire media tycoon, Rich learned that Armstrong’s agents wanted to take it to any network other than HBO. Rich intervened, warning HBO’s top executives that Jesse Armstrong had a big idea that he was about to take elsewhere. In short order, HBO ordered a pilot and then eventually ordered it to series. Rich was made an executive producer. That show, Succession, has won the Emmy for outstanding drama series twice in the last three years. The Permanent Campaign has sustained and served HBO to present day.

5. Launch your stories with an unorthodox event.

To generate as much quality noise as possible for their news stories, HBO hit on an effective tactic. Before an original movie first appeared on HBO, the network would stage an elaborate premiere in real life at a movie theater for a strategically selected group of guests, often in exotic locations. It was a great way, they quickly realized, to generate loads of free media attention.

In November of 1992, on the 75th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, HBO hosted a premiere of Stalin at a theater in Moscow. The screening was attended by the film’s cast, HBO executives, and a collection of Russian dignitaries. The movie, which starred Robert Duvall, had been shot during the tumultuous dissolution of the Soviet Union. On the night of the film’s premiere in Moscow, a controversy of sorts erupted in the theater. During the screening, many of the Russian officials in the audience took offense at the film’s depiction of Lenin’s wife. The Americans, they believed, had made her overly unattractive, an intolerable slight. Half of them walked out. The commotion aligned perfectly with HBO’s overarching goal for the event, which was to stir up some quality noise in front of the foreign correspondents who were stationed in Moscow covering the Kremlin for major American newspapers. It worked. HBO got a tremendous amount of international attention. This wasn’t just a cultural moment, it was a political event.

Years later, HBO started doing the same thing for the premieres of its TV series, starting with a big party for a new, and as of yet, unknown show called Sex and the City. At the time, the network had never done anything similar for its original series. Practically nobody had. Premier screenings for new TV shows were unheard of. Anybody could watch a new TV series from the comfort of their home, and the actors starring in new TV shows were rarely famous. More often than not, they were of zero interest to the paparazzi in the celebrity press. Whereas a movie could tell a complete story in two hours, what would you even show at the premiere of a TV show? One episode? Two? Three?

“Premier screenings for new TV shows were unheard of.”

Nevertheless, in the spring of 1998, HBO rented out a theater on 13th Street, just south of Union Square Park, in New York City. The screening would be followed by an after party at Lot 61, a nightclub in West Chelsea that specialized in 61 different flavors of martinis and featured a signature cosmopolitan. There would be no red carpet and few frills, but in the end, the resulting excitement and buzz felt well worth the effort. You could feel the anticipation building around Sex and the City, the show coming to life.

From there, the experiment mushroomed into a tradition. In the years that followed, the network would do it so often and with such enthusiasm that HBO series premieres would soon grow into a boozy fixture of cultural life in Manhattan, jostling with book parties and fashion shows for the top guests and the most attention from the press. Anyone hoping to get attention for their story, be it a movie or TV series or video game or book, would be wise to follow HBO’s playbook and kick things off with an unorthodox event.

To listen to the audio version read by authors Felix Gillette and John Koblin, download the Next Big Idea App today: