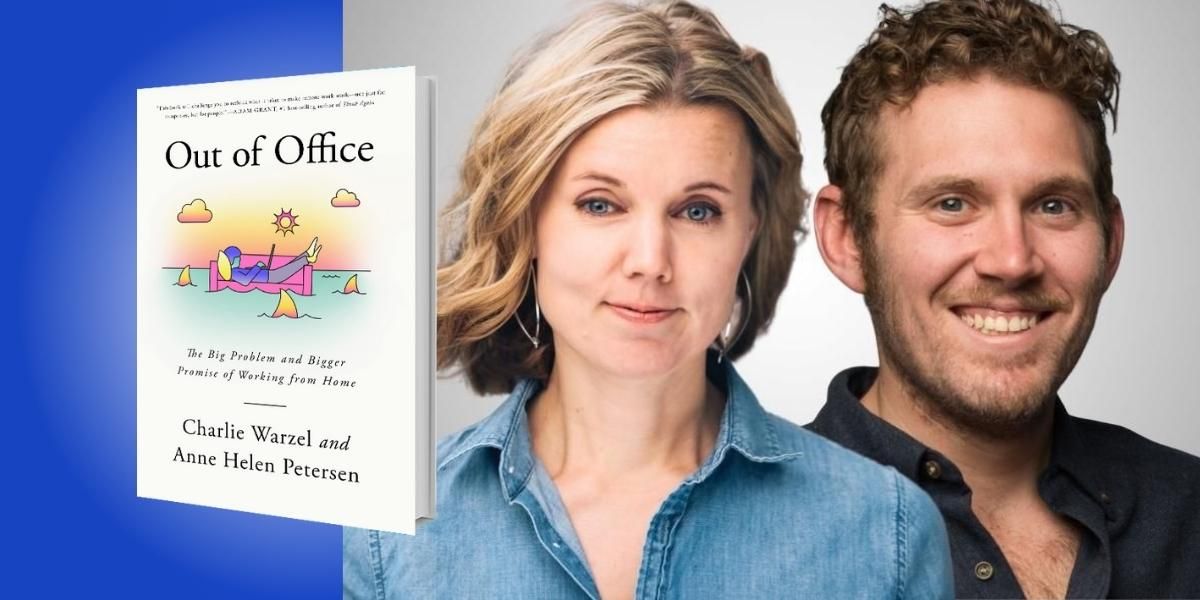

Charlie Warzel is a technology journalist and a contributing writer at The Atlantic. Anne Helen Petersen was a senior culture writer for Buzzfeed until going full-time working on her “Culture Study” newsletter on Substack.

Below, Charlie and Anne share 5 key insights from their new book, Out of Office: The Big Problem and Bigger Promise of Working from Home. Listen to the audio version—read by Charlie himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Work is broken, including remote work.

Work has long been a source of inspiration, dignity, and the cherished prospect of upward mobility, but it has stagnated and trapped us. For many knowledge workers, work has become an identity above all else, slowly eroding the other parts that make a rich, well-rounded existence. The dark truth of today’s remote work is that it promises to liberate workers from the chains of the office, but in practice it capitalizes on the total collapse of work-life balance.

We know this from experience. In 2017, we made the case that we could do our jobs as reporters even better from outside the city. After more than a decade of office life, we packed our car in Brooklyn and transitioned to working from home in Montana. Anne—more organized, and a bit more introverted by nature—settled right in. I struggled mightily. The “flexibility” of remote life really just meant flexibility to work all the time. Dreams of daily hikes in the mountains quickly evaporated.

The way forward begins with asking yourself, who would you be if work was no longer the axis of your life? How would your relationship with friends and family change, and what role would you serve within your community? Whom would you support, how would you interact with the world, and what would you fight for?

2. The future is flexible.

For the last 40 years, business books, financial publications, and industry leaders have fetishized the idea of corporate “flexibility.” Too often though, “flexibility” has been code for rapidly hiring and laying off employees as needed.

“Too often though, ‘flexibility’ has been code for rapidly hiring and laying off employees as needed.”

The future of office work has to be guided by a genuine form of flexibility in which the work, not the workers, becomes more malleable. Genuine flexibility is the linchpin of this work renovation project; without it, you can’t meaningfully shift work culture, your relationship to technology, or your dedication to community. Free workers from arbitrary schedules and you create space for all sorts of changes. In practice, genuine flexibility means reconceiving what tasks and collaborations need to be synchronous, what can be asynchronous, and how many days we’d like people to be in an office, for how long, and for what purpose. It includes broadening job descriptions to better meet the time and location needs of people who are disabled or juggling caregiving duties. It will require implementing respected boundaries to ensure that “flexible work” doesn’t spread into all corners of the calendar.

Establish guardrails, not boundaries. Boundaries are easily broken and shift the onus onto employees. Guardrails are structural. They are real and enforceable rules meant to protect people. Allocate the resources to make this happen—none of this happens if you don’t prioritize it. That means not working with a scrappy workforce, but one with enough employees that allows people to take meaningful time off.

3. Hybrid work is hard, and you have to be intentional.

A lot of remote work advocates don’t admit that flexible work is hard. It introduces friction into daily processes. Two words that appear over and over again in our book are “intentional” and “design.” That’s because the only way to make flexible work succeed is to pay close attention to the small details and build policies that fit your organization and the needs of employees.

“The only way to make flexible work succeed is to pay close attention to the small details and build policies that fit your organization and the needs of employees.”

At Twitter, hybrid work is inadvertently creating a new hierarchy based around physical face time. Single parents, workers with elderly family members, disabled employees, and those who simply don’t want to live in proximity to the office risk being overshadowed by those who come in every day. So, Twitter is trying to destroy the fear of missing out and level the playing field by making the office less appealing. They’re attempting to actively disincentivize coming back to the office full-time. This starts with the way the office is arranged and the expectations for people within those spaces. The company plans to get rid of physical team spaces, and will transition fully to “hot desking”—unassigned desks—with some spaces reserved for deep work and others for busier, more social areas. They’re also re-thinking amenities, including free first-rate food at all hours, which tethers employees to the office.

For many managers and executives, the idea of introducing friction into a functional workplace might sound counterintuitive, or straight-up foolish. But, at least in its earliest stages, Twitter understands that merely layering remote work atop the current workforce paves a path to dysfunction.

Early in the pandemic, Dropbox gathered internal data on productivity patterns and took input from employees as to what was working and what wasn’t. The company made a huge leap to shift all individual work to remote, with options for teams to come together episodically. They planned a new style of office, dubbed “studios,” for episodic work, but they’re constantly surveying employees for input on adjusting the new work environments and processes. They’re even willing to scrap long-term plans that don’t work in practice.

“Merely layering remote work atop the current workforce paves a path to dysfunction.”

4. Changing how we work is a long-run investment.

Leaders chronically underestimate the amount of intentional planning and time it will take for the true benefits of remote or hybrid work to materialize. Flexible work isn’t a line item to add to your Chief People Officer’s job description; it is a full-time job that requires a leader and dedicated team members to handle redesigning policies, workflows, and perks.

Gitlab’s Darren Murph is, perhaps, the first person to hold the title of Head of Remote Work. He told us that leaders ought to look to the trajectory of the Chief Diversity Officer role. What started as a boutique HR initiative in many tech companies was actually a wave of change cascading through companies of all sizes. “It seems obvious now to hire a Chief Diversity Officer,” Murph told us. “But companies refuse to see the obvious.”

Nobody can see the future. We can, however, get a sense of what might seem obvious tomorrow, but only if we stop obsessing over short-term gains.

Murph likes to think of designing durable remote infrastructure as a kind of compounding interest. “I keep telling companies, don’t expect savings right away. If you own real estate and have ten- or twenty-year leases, it won’t happen quickly,” he said. Short-term thinkers will see these leases as a reason not to change their policies, but what happens when the lease expires? “They’ll look around and see their competitors,” Murph said. “And those competitors invested early in a remote-first approach, and now they’re able to easily adapt to whatever’s next. Meanwhile, that company will be flat-footed.”

“Nobody can see the future. We can, however, get a sense of what might seem obvious tomorrow, but only if we stop obsessing over short-term gains.”

5. Ultimately, it’s not about where you work, but how you work.

Our book is less an argument for remote work than it is an argument to find a better, more equitable and sustainable way to work that recognizes humans as three-dimensional, with rich lives outside their careers. Remote work is a way for us to talk about re-imagining a lot of the old, vestigial first principles of office life and finding new ways to design the future of knowledge work.

Remote work forces you to change the how. It is not a cure for crappy management or a bad business model or a bad product—it is merely an organizing principle. Being removed from the luxury of tapping anyone on the shoulder at their desk or bumping into somebody in the elevator means thinking more intentionally about how you work. Stripping out some of the artifice and vestigial norms of the office gives us the chance to see our companies as what they really are, what they’ve always been: a collection of human beings.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Charlie Warzel, download the Next Big Idea App today: