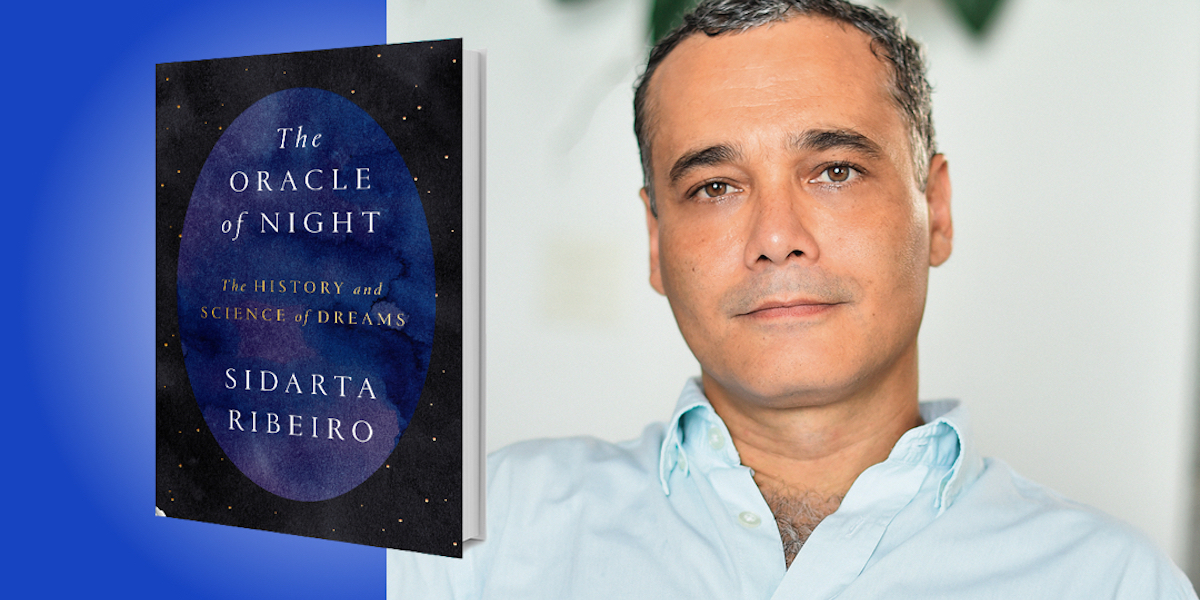

Sidarta Ribeiro is a neuroscientist and the deputy director of the Brain Institute at the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte in Brazil. Below, he shares 5 key insights from his new book, The Oracle of Night: The History and Science of Dreams. Listen to the audio version—read by Sidarta himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Sleep and dreaming are essential parts of a healthy life.

Among the many roles sleep and dreaming perform, the most important may be helping us process our memories. When we sleep, our memories are replayed in an associative manner—and with some noise—through the reverberation of patterns of neuronal activity. Slow-wave sleep, which prevails in the first half of the night, helps us process declarative contents that can be quickly learned and retrieved based on mental representations of people, animals, places, objects, and events. REM sleep, which dominates the second half of the night, plays a major role in the processing of emotional and procedural memories, such as dealing with frustration or riding a bicycle. The interplay between slow-wave sleep and REM sleep allows memories to migrate from one place to another within the brain, undergoing important transformations over time.

And a good night’s rest also facilitates creativity. Salvador Dalí’s paintings, the first sewing machine, the periodic table, and the song “Yesterday” by Paul McCartney all came from dreams. In the past 20 years, neuroscientists have shown that REM sleep and dreaming indeed increase memory restructuring, task-solving, and creativity.

“Salvador Dalí’s paintings, the first sewing machine, the periodic table, and the song ‘Yesterday’ by Paul McCartney all came from dreams.”

2. Sleep and dreaming are at risk, and so are we.

The adaptive benefits of sleep and dreaming clash with the sharp reduction of sleep and dream recollection in most contemporary societies. With all the screen stimuli that have invaded our lives, the opportunity to sleep well and dream profusely is increasingly at risk. Sleep loss can lead to memory deficits, depression, obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and Alzheimer’s. Dream loss can lead to a lack of insight into our desires, fears, challenges, and the consequences of our actions.

And that may not even be the worst of it.

We’re living an evolutionary catch-22. If we continue to develop as we have in the past century, the environment will collapse. And if we slow down this development, the economy will collapse. If there is another way forward, our sleep-deprived imaginations cannot conjure it. Perhaps we struggle to imagine a different kind of future because we have abandoned the habit of remembering our dreams and sharing them with others.

3. Dreams evolved in mammals as a probabilistic oracle.

Our ancestors believed that dreams held the key to future events. Priests and fortune-tellers were valued for seeing in the plot of mysterious dream symbols a practical enigma whose interpretation could clarify the course of life.

“In dreams, we use yesterday’s events to sketch tomorrow’s contours—assessing dangers, discovering opportunities, and guiding decisions.”

How is it possible to reconcile the materialist explanation of dreams with the premonitory function attributed to them by so many different traditions? To answer this question, we need to trace the evolutionary origins of dreaming. Birds, reptiles, and octopuses, despite having active sleep episodes somewhat like mammalian REM sleep, do not have the ability to sustain it long enough to generate the cinematic dream experience found in mammals. The capability to sustain dreams not for seconds but for dozens of minutes gave mammals the key cognitive power of simulating complex behavioral strategies, generating a neurobiological oracle that is not deterministic but probabilistic. In dreams, we use yesterday’s events to sketch tomorrow’s contours—assessing dangers, discovering opportunities, and guiding decisions.

4. Dream sharing accelerated cultural change.

Our swift journey out of caves and into outer space was propelled by a human skill that is unique among mammals: the ability to tell others about our dreams. The communal interpretation of dream reports was a traditional source of group cohesion, creativity, and wisdom in the face of a hostile world. Our ancestors developed sophisticated rituals to access the knowledge hidden in the dream mists. Eventually, dreams became known as a gateway to interact with dead ancestors and godly entities who would counsel or command the dreamer’s actions. The frequent and highly regarded contact with dream entities, which vigorously enriched the inner life of our ancestors, led to the unprecedented cultural accumulation that catapulted us into the future.

5. Together, we can dream up a better future.

Our dreams have lost their luster. We do not look to them for guidance at home, in school, or at work. Upon waking in the morning, we don’t stay quiet in our beds long enough to reconstruct the dreams from which we just awoke. If we are going to survive as a species, we need to renew our ancestral commitment to concerted action by sharing our dreams about the future.

To listen to the audio version read by Sidarta Ribeiro, download the Next Big Idea App today: