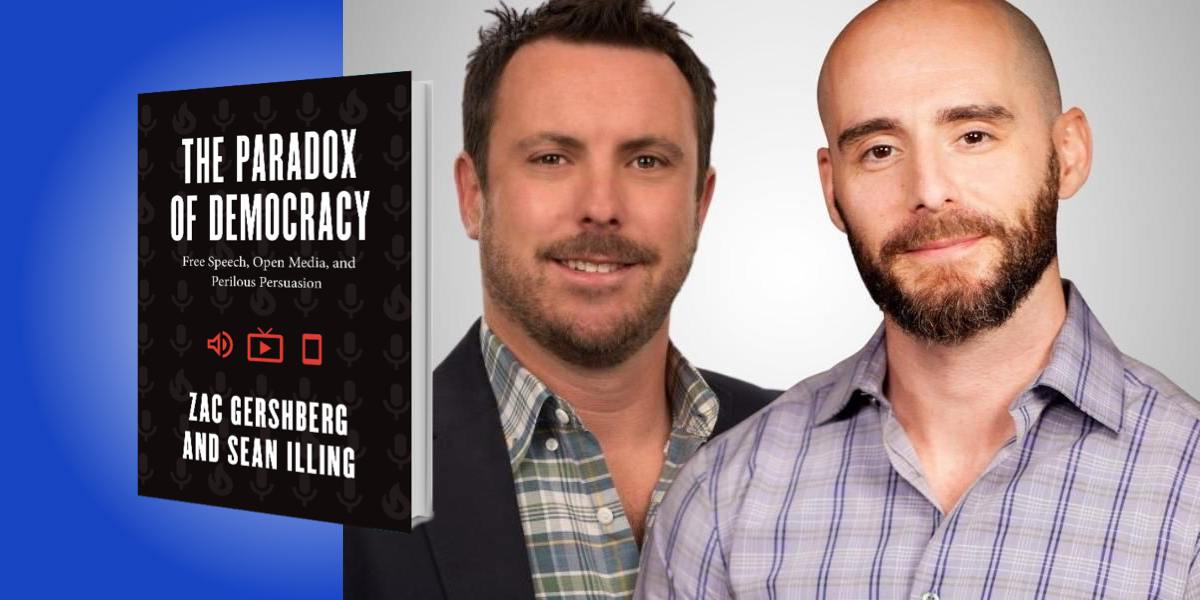

Sean Illing is the host of Vox Conversations, and was previously a professor of politics and philosophy, as well as a paramedic in the United States Air Force. Zac Gershberg is a professor of journalism and media studies at Idaho State University.

Below, Sean shares 5 key insights from their new book, The Paradox of Democracy: Free Speech, Open Media, and Perilous Persuasion. Listen to the audio version—read by Sean himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Isegoria.

An invitation for citizens to speak freely heralded the world’s first democratic assembly on a rocky hillside in Athens over 2,000 years ago. The Greek term for free and equal speech, isegoria, was considered synonymous with democracy. But while free expression may be the defining characteristic of democracy throughout time, that doesn’t mean it is without consequences or limitations.

In Athens, not everyone was a citizen. Women and slaves were excluded, and the Athenian assemblies were not above tribalism and ostracism, punishing those (like Socrates) who did not conform to public expectations. “Pay no attention to my manner of speech,” Socrates explained to the jury when defending himself on charges of corruption. He wanted only the truth to stand alone and set him free. Alas, that is not how free speech works, and Socrates was condemned.

Neither democracy nor free speech can proceed without rhetoric, the effective use of persuasion. This may strike us as unseemly, and that’s why Socrates and his pupil Plato distrusted democracy and rhetoric altogether. Yet the outrageous charlatan, the conniving cynic, and the inspirational leader all peddle rhetoric, one way or another—which is why persuasion, not truth, reigns supreme in a free and open society.

2. The Age of Liberal Democracy is over.

This might take some getting used to because the traits typically associated with democracy—honoring election results, fairly applying the rule of law, and informing public opinion through facts—reflect a century of aspirational thinking and cultural norms that buffered our political world. The characteristics of liberal democracy operated like fairy dust, working so long as politicians and the public chose to believe in them. But that is no longer the case, and the status quo is gone.

“The paradox is that the opportunities democracy permits often undermine democracy itself.”

The much-vaunted marketplace of ideas, no less than a more globalized economy of free trade, did not translate to a flourishing of good governance and truth. Populist figures like former President Donald Trump and his followers who stormed the Capitol on January 6 reflect these changes. We see more successful populist examples in Hungary, under Viktor Orbán, and with Turkey’s Erdoğan. What we are left with is democracy-as-such, understood in the classical sense that people use their voice to obtain and exercise power. Our problems are different, but not new.

The paradox is that the opportunities democracy permits often undermine democracy itself. The ancient Athenian assembly once voted itself out of existence, in favor of oligarchy, and the powerful senate of the Roman Republic mostly welcomed the imperium of Caesar. There are many exit ramps on the democratic highway, and not all of them are liberal. Our contemporary landscape, culturally fragmented by social media and the digital world, inhibits rather than encourages solidarity. Liberal democracy continues as a project adhered to by many centrists in the realm of politics, and can win elections and pass legislation from time to time. But we can no longer rely on the assumptions that the law, media, or our institutions will be respected and guide us. But recognizing this transition is not a cause for cynicism and hopelessness—it should inspire the call for ethical commitments among the public.

3. “The Media” does not exist.

We hear that the media is biased, too sensational, and doesn’t do enough to save democracy. But such thinking is as myopic as it is grammatically incorrect. “Media” are plural, and function as total communication environments with different economic and technological incentives that steer content, depending on the platform. We understand reality through media, which structure our world.

“Let go of ‘the media’ as a singular entity, once and for all.”

Different media have different characteristics, which we should pay close attention to. Take FOX News and MSNBC—we might see one as biased to the right and the other to the left. But their real bias, as media, owes to the pathologies of cable television news. A host introduces a topic and pundit guests are invited to comment, trying to spin the conversation in their direction. Then we move on to the next segment. The form of cable TV remains the same no matter what you watch. Marshall McLuhan understood this point in his famous utterance, “The Medium is the Message.” Notice he didn’t say “the media,” and that’s because effective thinking about communication teases out the individual differences of platforms apart from the biases within the content. So let go of “the media” as a singular entity, once and for all. It’s time we began thinking about the ways in which media surround us as a multiplicity of influences in our world.

4. Morse’s Macrocosm.

What hath God wrought? That question from 1844 marked the first message sent via electromagnetic telegraph line, from Baltimore to Washington, D.C. The author of the message, Samuel F.B. Morse, expected harmony from his invention. “I trust that one of its effects,” he said, “will be to bind man to his fellow man in such bonds of amity as to put an end to war.” Human society did not evolve as he imagined, and Morse, who had met Louis Daguerre and popularized photography in America, should’ve known better. Whereas photography froze moments of time in space, the telegraph collapsed the distance of space to spread timely news. You might say we’ve been living in “Morse’s Macrocosm” ever since.

Connecting our world with information and images brought nationalistic impulses that led to nativist anger at immigrants and war—and an ongoing obsession with celebrity politics. Why, the messages in 1844 were timed to coincide with the political party conventions in Baltimore. Morse himself was commissioned as a young painter for a portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette in the 1820s. In the 1830s he wrote as a paranoid conspiracy theorist against Roman Catholicism for the New York Observer, with a failed bid running for Mayor of New York. Yet Morse also supported Polish efforts to declare independence as a democracy. His name may live on for the linguistic code, but the access and pathologies of Morse’s Macrocosm is a legacy firmly rooted among us 200 years hence.

“Connecting our world with information and images brought nationalistic impulses that led to nativist anger at immigrants and war—and an ongoing obsession with celebrity politics.”

5. Fascism is spectacle.

Historians and political theorists have continually bickered over how to define the “fascist minimum,” an official set of characteristics that can determine when fascism exists. But we think of fascism less as a form of government and more as a means to power. Fascism is an ugly collision between mass media and mass politics, where a propagandized media campaign seeks to overcome democracy.

This was true of Benito Mussolini in Italy, who relied on the Milanese newspaper and open-air rallies to express contempt for democracy as he was trying to recapture the glory of the Roman past. The March on Rome, from 1922, never even happened: the prospect of it scared Italian leaders enough to hand him the government. The same could be said of the Nazi Party. The Beer Hall Putsch was a disaster, and Hitler, having been arrested, used his treason trial to make a public mockery of democracy and promise a return to German greatness. It took another decade of disruptive propaganda for the Nazis to finally come to power, and they were invited by conservative leadership who thought they could be controlled.

But well before the time of World War II and the Holocaust, Italy and Germany had already become totalitarian governments, brooking no dissent. Fascism had served its purpose as a pretext to gain power through spectacle, and what followed in its wake were some of the most gruesome moments in human history.

To listen to the audio version read by co-author Sean Illing, download the Next Big Idea App today: