Elizabeth Cripps is a moral philosopher and a Senior Lecturer in Political Theory at the University of Edinburgh, where she researches and teaches climate justice. She is also the author of What Climate Justice Means and Why We Should Care. She has a Master’s and PhD in Philosophy from University College London.

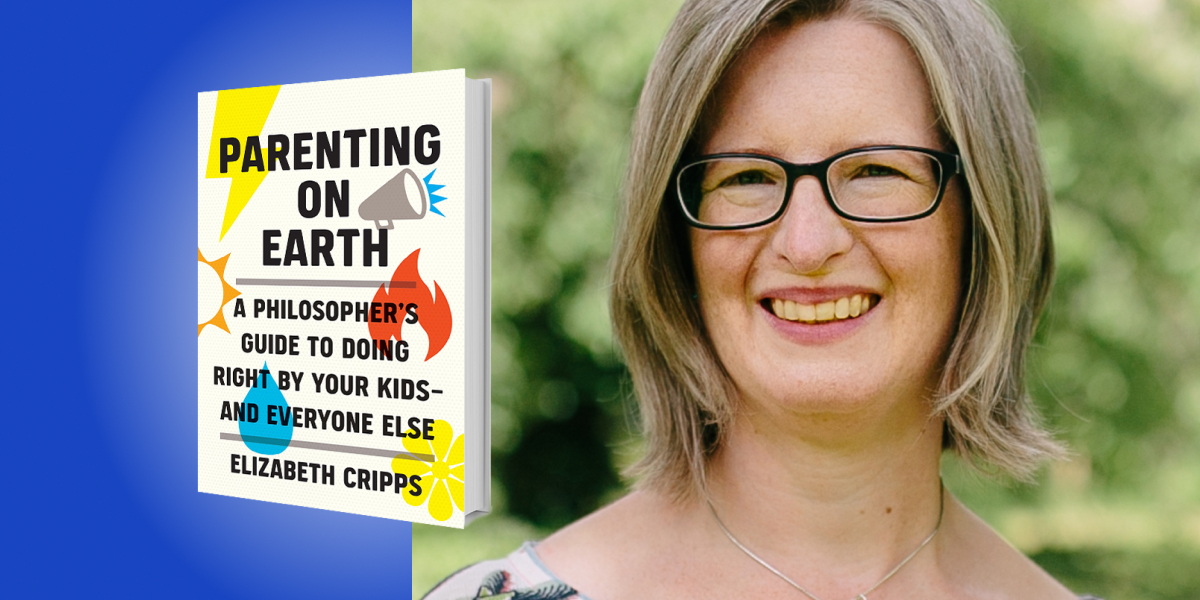

Below, Elizabeth shares 5 key insights from her new book, Parenting on Earth: A Philosopher’s Guide to Doing Right by Your Kids and Everyone Else. Listen to the audio version—read by Elizabeth herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. “Good parenting” doesn’t mean what we think it does.

In societies like the US or the UK, we think we’re being “good parents” if we focus most of our time and money on our own kids, and we tend to do that in a very individualistic, consumer-orientated way. We buy them toys and worry about their career prospects; some parents pay school fees, buy their kids cars, throw them expensive parties, or take them on luxury holidays. We think we’re doing the best for our children by piling up stuff and money and opportunities for them. But that’s a mistake. While we’re focusing on them in this one, narrow way, we’re neglecting them in a much bigger way—and we have an incredible opportunity, right now, to change that.

It helps to think about it like this. What must we do for our kids because they are our children? (In other words, what do we owe them?) Most philosophers would say we should take care of them as children and help them to cultivate the tools they’ll to lead full lives as adults. These would be things like education, healthy bodies, and resilient minds. But, as things stand, our children won’t have a world fit to live a full life in. They face climate change, antibiotic resistance, and future pandemics as bad as or worse than the one we are still emerging from, not to mention continued institutionalized racism, sexism, and horrific injustice.

As parents, if we don’t try to change this, we make a mockery of everything else we do to prepare our children for their adult lives. More simply put, truly loving our kids means protecting their future if we can. As things stand, we’re reading bedtime stories in a house that’s burning down.

2. Being a good parent means being a good global citizen.

Imagine this possible future: Climate change is much worse. Your child, now fifty, lives in a carefully constructed dome: a beautiful, safe place for the privileged minority, although probably only for his generation. He has friends and loved ones, glorious art, amazing culture, artificial plants, even fake mountains. Outside the dome, the world is decimated. The rest of humanity—as well as the few remaining other animals—starve and die of disease. Is that really the future you want for your child? I doubt it.

In saying that good parenting means protecting our kids’ future, I’m not just saying that privileged parents, like me, should shield their own children from the direct health or economic costs of something like climate change—although we’re not even doing that, right now! Being a good parent, as well as a decent human being, means trying to leave a just world. That’s one where all future generations can flourish, where biodiversity is protected and people aren’t dying for want of antibiotics, or being routinely attacked because of their gender or the color of their skin.

“Being a good parent, as well as a decent human being, means trying to leave a just world.”

We can see this philosophically. Our kids are individuals with their own lives to lead, but they are also human beings, among other humans. To put it another way, they are moral beings like we are. As such, they are marred by the continued atrocities in the world—all the more so if they are complicit in the systems that are causing them. There’s also plenty of empirical evidence that injustice, like institutionalized racism, makes everyone worse off.

To be clear, privileged parents should not only be worrying about global poverty or discrimination to spare their own kids some moral discomfort. We should all fight injustice because we should all care about our fellow human beings. We can’t use our responsibilities to our own kids as an excuse not to act. We can’t say we’re too busy being parents, because if we recognize our children, like ourselves, as full human beings, then we should do this for them too.

3. Good parenting means making hard choices.

I know this isn’t easy. For one thing, we don’t have unlimited time, money, or emotional energy. Parenting is already exhausting! During the pandemic, it was even harder. Many of us have other commitments, including to elderly parents. We have interests and ambitions of our own. In addition, we need to balance these new aspects of “good parenting” with all the other things that we still need to do for our own kids: things like day-to-day care, especially if they have extra needs; securing their education; and building their emotional health.

“If your child could look back, as an adult, on this crucial period in global and planetary history, what would they rather you had acted on?”

There’s no quick fix for finding this balance, but there are some questions we can ask ourselves, to find a way through. For example, which life choices are necessary to give your child a fair shot at a decent future, or to maintain that all-important parent-child relationship? Which, on the other hand, are just cultivating tastes that have no place in a sustainable future? What do you truly need, day to day, to sustain yourself as an individual, a parent, and a human being? If your child could look back, as an adult, on this crucial period in global and planetary history, what would they rather you had acted on?

4. Psychology is not morality.

As well as being practically daunting, all this is psychologically difficult. We’re socially and individually wired to think short-term, to rank things by their economic worth, and to treat the natural world as a commodity. But that’s a psychological explanation. It’s not a moral justification for doing nothing, especially when we can turn to psychology itself for the tools that would help us think and act differently.

For example, we can use strategies to counter our short-termism, from writing to our children in thirty years’ time, to more “deep time” geological thinking. We can try to drop our distractions and re-engage mindfully with the non-human world. We can learn to cultivate true self-care, instead of the consumerist version we are always being sold.

We must also acknowledge incredibly difficult emotions, like fear, guilt, eco-anxiety, and frustration, instead of suppressing them and letting them turn into despair or disavowal. We can try to work through them, and help our children to do the same. In the process, we might even find a kind of active or earned hope, as we try to build a better future.

5. Parents have power.

I can’t protect my children alone. Nor can you. We can’t fight global emergencies without changing the behavior of culpable political institutions and powerful corporations. In this interconnected world, morality is about much more than what you achieve as an individual.

“On one famous estimate, it takes only committed activism by 3.5 percent of the population to provoke meaningful change.”

As parents, we can raise the next generation to understand the challenges they’ll face and respond with justice, care, and resilience. We can live differently, as families. We can help our kids not to become hooked on consumerism or high-carbon lifestyles. Perhaps most importantly, as a group, parents have huge economic and political power.

On one famous estimate, it takes only committed activism by 3.5 percent of the population to provoke meaningful change. In the US, parents with kids under 18 living at home made up 19 percent of the population in 2020—and that’s nothing like all parents. Over the years, parents have led incredible movements. In the 1980s, Black mothers on Carver Terrace, Texarkana, learned that they were raising their families in homes built on toxic waste. They protested, despite huge obstacles, and kept on protesting until eventually, Congress organised a buy-out of the homes.

Now, grassroots parent climate activist groups are growing around the world, they’re connecting with each other. They are using creative and determined methods to make their voices heard. Only last week, mother activists were singing and dancing outside the headquarters of insurers Lloyds of London, trying to persuade their chairman (a dad of four) to stop insuring fossil fuels. There’s an opportunity to be part of that.

To listen to the audio version read by author Elizabeth Cripps, download the Next Big Idea App today: